Memphis Blues, Mississippi Delta Roots

A random jaunt through the hallowed region that flavors the culture of its urban cousin to the north

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hoseshoe-casino-Tunica-Mississippi-631.jpg)

Untutored Yanks like me are sometimes surprised to learn that the fertile Mississippi River Delta extends all the way up to Memphis, Tennessee. But the influence of Mississippi—both the river and the state—is palpable in the Bluff City. Dig into almost any important Memphis phenomenon or personality—blues-tinged or not—and you’re liable to find Mississippi roots.

“Memphis is the capital of the Delta, and we’re on the spine—Highway 61,” the blues historian and filmmaker Robert Gordon told me over lunch one day on the south side of Memphis. “All roads in the Delta lead to 61, and 61 leads to Memphis.”

So it came to me one bleary-eyed Saturday night that to understand Memphis at all, I would need to venture farther south. At the moment, I was in a midtown Memphis juke joint, raptly appreciating a young blues singer named Ms. Nickki, who had told me she was from Holly Springs, Mississippi, where her family had raised horses and taught her to sing in church.

On Sunday morning, I thought I’d start out at the Full Gospel Tabernacle Church, where legendary Memphis soul singer the Rev. Al Green sometimes leads the service. But then I consulted with my gracious hosts Tom and Sandy Franck, who run the charming Talbot Heirs Guesthouse in downtown Memphis. They recommended the gospel service at First Baptist Beale Street Church right nearby.

When I arrived at the historic church, though, I discovered that once every five weeks they switched the Sunday school session with the main service, and this was that week—so I had just missed the service. It was a major disappointment, but what could I do? Move on to the day’s primary mission: a day trip through the Delta.

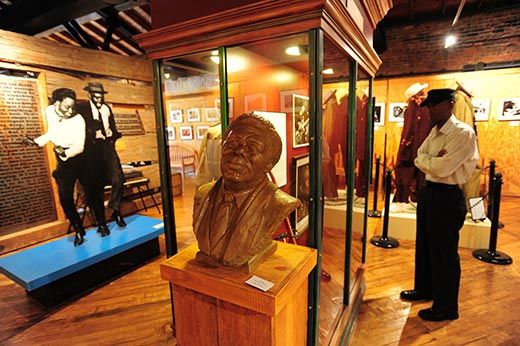

I jumped in my rented Mustang, put the top down, tuned the radio to a gospel station at the upper end of the AM dial, and pointed south toward Highway 61. Destination: Clarksdale, Mississippi, the very cradle of the blues. It’s where—at the crossroads of Highways 61 and 49—legend says bluesman Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil to gain his talent. It’s where Bessie Smith died (not in Memphis, as Edward Albee seems to have believed). It’s where the Delta Blues Museum lives. And it’s only 80 miles down the road.

Within 15 minutes, I was passing men in overalls selling humongous watermelons off an old flatbed truck. You see billboards luring Memphians down to the Tunica, Mississippi, casinos for the slots and craps action. A restaurant ad promised 48-ounce steaks—the term “doggie bag” seemed suddenly inadequate. Pretty soon, I was in the Magnolia State, easing by rice and cotton fields that stretched off to the horizon. The soil looked awfully rich to my non-expert eyes.

En route, I couldn’t resist a quick detour into Tunica’s gambling emporia, choosing the Horseshoe Casino because it looked less generic and because it sits next to the Bluesville Club, whose marquee advertised upcoming shows with Booker T. & the MGs and B.B. King. Ms. Nickki told me she’d appeared there, too. Hey, I was feeling lucky, and no sooner did I shake hands with the one-armed bandit than I’d won a $35 jackpot. Good time to scoot.

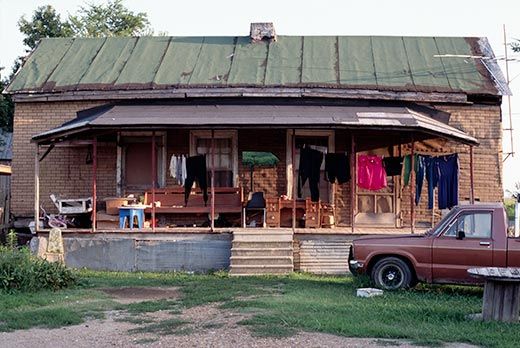

I soon veered off onto Old Highway 61, a back road dotted with shacks—a corrugated community, you might say—leading after a while into the sun-drenched main square of old Tunica. I wondered about this musical place name, which sounds as if it could be a tuneful cousin of the harmonica. In fact, I learned later, Tunica is named for the Indian tribe that once lived in the area and now shares a reservation with the Biloxi tribe in Marksville, Louisiana. The Tunica were much put upon by the more aggressive Chickasaw, who even sold a number of them into slavery in South Carolina about 300 years ago. Interestingly, the Tunica language, now extinct, is said to have no connection with any other family of languages—a kind of North American Basque. Since the Tunica and the Biloxi couldn’t understand each other, they resorted to French.

I stopped for lunch at the delightful-looking Blue & White Restaurant back on 61. It’s been there since 1937, and from all appearances, hasn’t changed much. My genial waitress, Dottie Carlisle, recommended the $9 all-you-can-eat Sunday buffet special. I heaped on some fried chicken, mac ’n’ cheese, Brussels sprouts, yams, turnip greens and black-eyed peas, created a little puddle of gravy, and got down to work. Afterward, Dottie insisted I sample the peach cobbler, which later caused me to slide the driver’s seat back an inch or two. Before Dottie would let me go, though, she led me into the kitchen to meet Dorothy Irons, who had cooked up this feast. She said she’d worked at the Blue & White since 1964, which was an especially tense time in Mississippi. But as I looked around the restaurant—where white and black employees acted like sisters, where an elderly black woman in her Sunday finery took her place right next to a table of good ol’ boys without anyone seeming to take notice—I had to conclude that while the legacy of that past persists, there was no question a whole lot had changed, too.

Finally I approached Clarksdale. Looking across the flat terrain, there were major storm clouds ahead and as I entered town, it was kicking up pretty good. I got lost trying to find the Delta Blues Museum, and there seemed to be no one around who could even give me directions. At last I stumbled upon the museum, which sat across an empty lot—not a good omen.

As I walked across the deserted space, I caught sight of the only other human who had ventured out in Clarksdale on this steamy Sunday afternoon—a barefoot, freckle-faced white boy splashing through the puddles like Gene Kelly. The kid eyed me from a safe distance.

“It’s closed,” he yelled.

“Looks like it,” I conceded, wondering about this little guy playing freely all by himself. He was small, but had the toughened air of a much older boy. “How old are you?” I asked.

“Nine.”

“Are you with your parents or somebody?”

At that, his eyes widened and he tore off across the lot, looking back warily every ten yards or so.

I think I just met Huckleberry Finn.

So now I’d missed both the gospel service in Memphis and the Delta Blues Museum, but I still had this growing feeling that there’s something powerfully different about this corner of the world. I just couldn’t quite put my finger on it, and realized it might be a long time before it really sunk in. I decided to head east toward Oxford, the home of Faulkner, the University of Mississippi, John Grisham and the Oxford American. Must be a fairly civilized place, I thought, though it was also the site of violent white resistance in 1962 when James Meredith enrolled as the university’s first black student. President Kennedy had to dispatch 16,000 federal troops to restore peace.

Not five minutes out of Clarksdale, the torrential rains caught up with me again. Radio reception cut out, the road disappeared under water, and an 18-wheeler rumbled by at about 75 miles per hour in the opposite lane, sending a small tsunami my way. I barely saw it coming. I decided to play a stupid game: I’d count to 30, and if the visibility didn’t improve, I’d pull over and wait it out. At 23, it started to relent. I kept going.

Halfway to Oxford, you pass though Marks, Mississippi, which happens to be the birthplace of Fred W. Smith—founder and CEO of Memphis-based FedEx. But the town’s claim on history comes mostly from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was stirred to tears by the conditions he found there in 1968—poverty so entrenched that hundreds of children went without shoes or regular nutrition. He decided that Marks was an appropriate place to begin his Poor People’s March to Washington, D.C.—an epic campaign he didn’t live to see concluded. One-third of Marks’ residents still live in poverty.

Oxford, Mississippi, deserves a journey of its own—I’m afraid my quick foray through the Ole Miss campus and some charming downtown streets only whetted my appetite. Having just fallen under Ms. Nickki’s spell, though, I was more curious to continue on to her native Holly Springs, to complete the circle.

There are other important Memphis connections in Holly Springs. It was the birthplace of the legendary Memphis machine politician E.H. “Boss” Crump, and of Ida B. Wells, the early civil rights advocate and feminist who published her newspaper, Free Speech, in the basement of the First Baptist Beale Street Church. Holly Springs was also one of the hometowns of the Confederate general Nathaniel Bedford Forrest, who was so lionized in Memphis that in 1904, the city erected an impressive equestrian statue to mark his grave site in the Union Avenue park named for him. Considered a brilliant military tactician, he was also accused of massacring black Union prisoners under his command at Fort Pillow in 1864; Forrest was later installed as the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. For his Confederate zeal, he is still revered by white supremacists, more so than the kinder, gentler Robert E. Lee, for example. Needless to say, Forrest’s continuing place of honor in a majority African-American city sparks some controversy.

Holly Springs today has a satisfying old main square that made Oxford’s even look a little fussy. But it was late in the day when I finally arrived, and there were notable sights I’d probably never get to see, such as the juke joint Robert Gordon described as his all-time favorite. He was taken there by Junior Kimbrough, a local bluesman. “It was in a house in the middle of a cotton field,” Gordon recalled. “The party was roaring. They were selling fruit beer in the kitchen, and Junior was throwing down in the living room.”

In case you’re unfamiliar with that expression, it’s a high compliment.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)