When the Mob Owned Cuba

Best-selling author T.J. English discusses the Mob’s profound influence on Cuban culture and politics in the 1950s

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/5f/e35f6397-e560-49b1-ab31-7788ea301392/sqj_1610_cuba_mob_02.jpg)

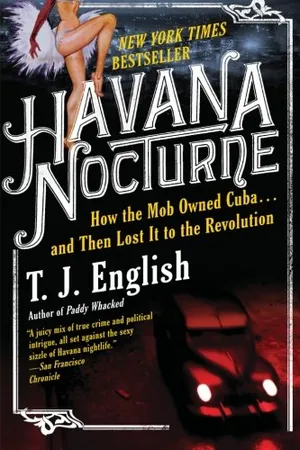

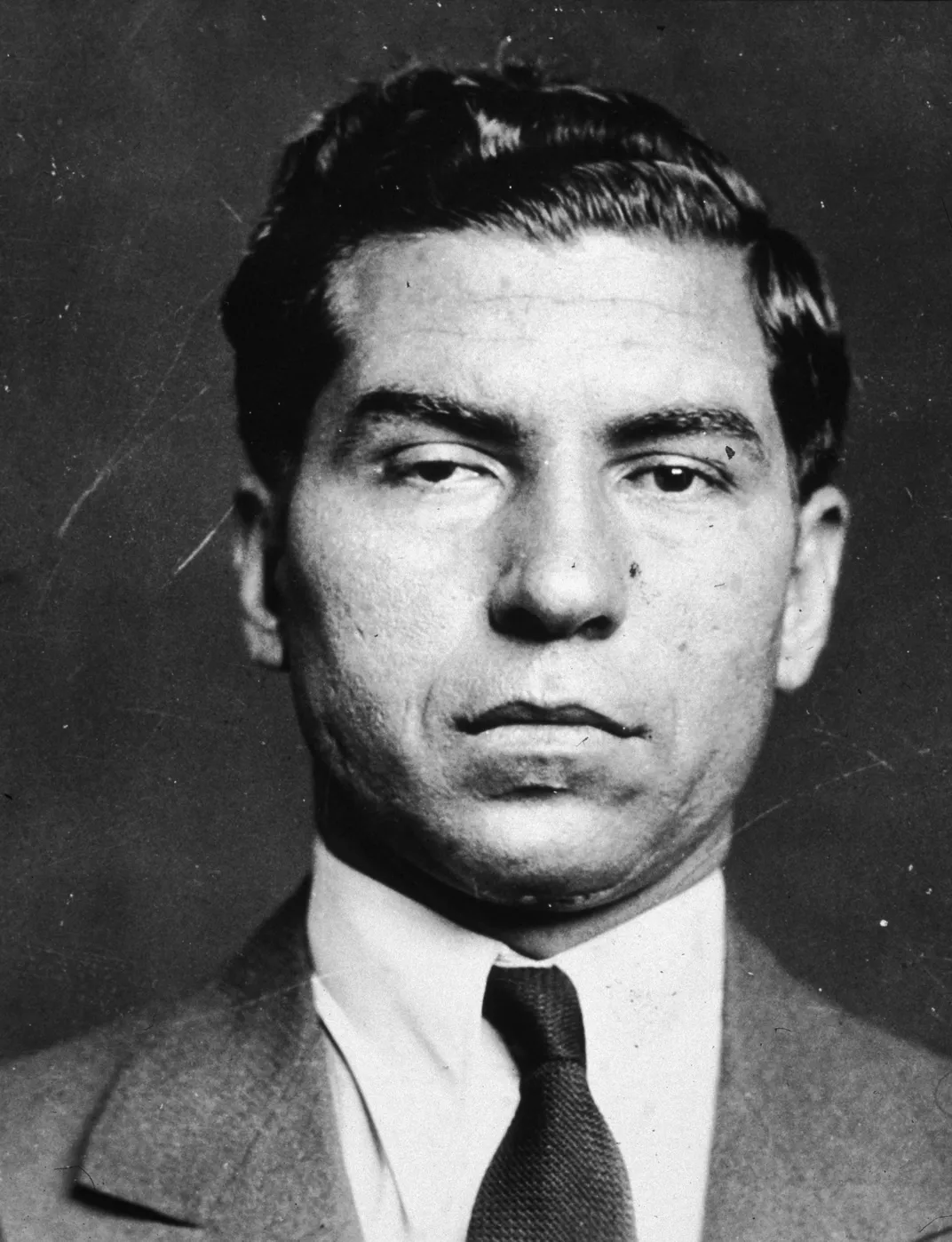

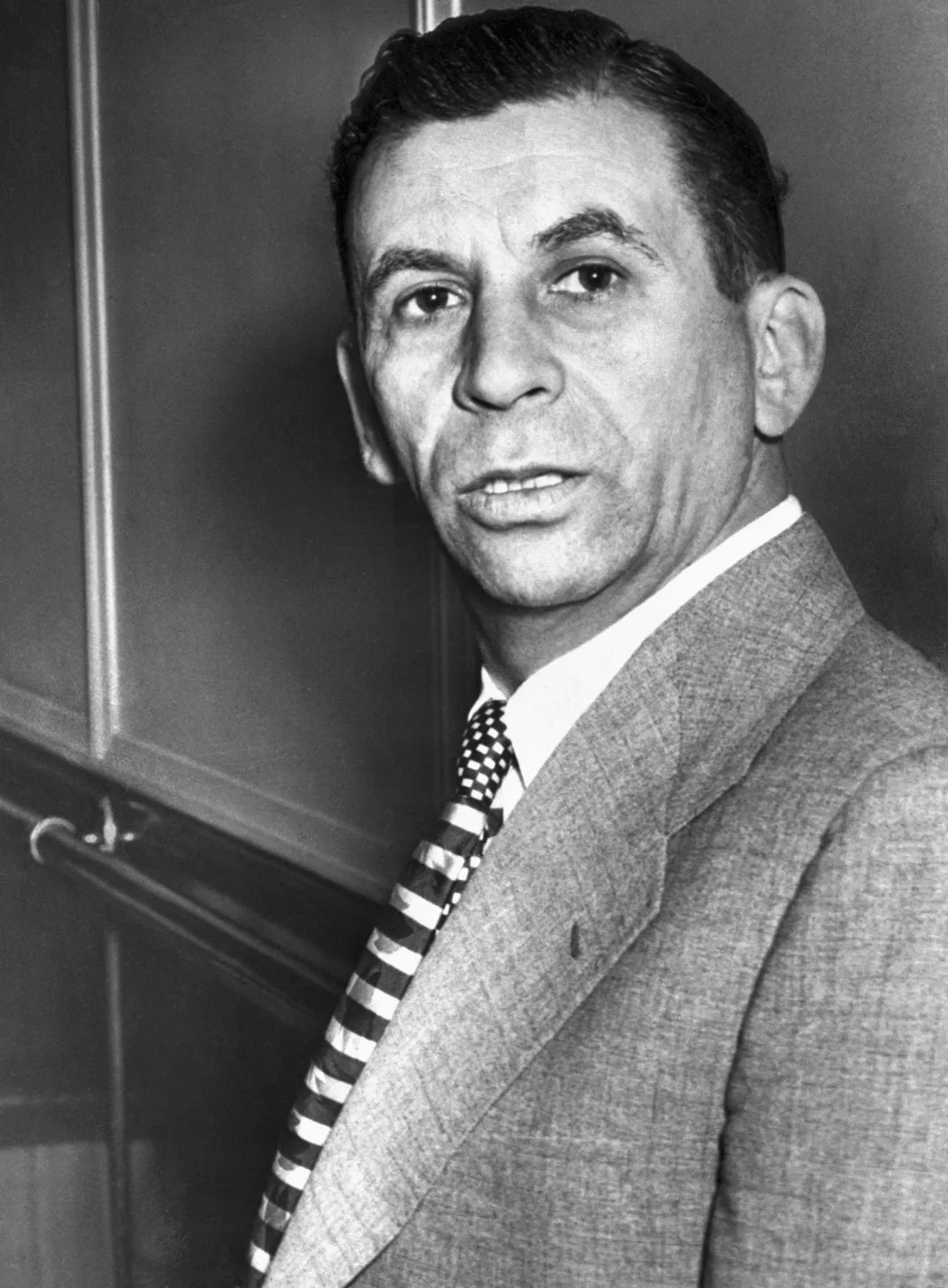

T. J. English, a best-selling author of books about organized crime, caught the Cuba bug as a child watching Fidel Castro on newscasts. Later he fell under the spell of Cuban music. His book Havana Nocturne: How the Mob Owned Cuba … and Then Lost It to the Revolution takes readers to the underbelly of Cuba in the 1950s, when mobsters like Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Meyer Lansky turned the island into a criminal empire and unwittingly launched a vibrant Afro-Cuban music scene that continues to this day.

When Smithsonian Journeys contacted English recently by phone, he explained how Frank Sinatra became a draw for mob casinos in Havana, how the Castro-led revolution in Cuba and its subsequent diaspora had a protracted, corrosive effect on American politics, and how the ghosts of the 1950s still haunt the streets of Havana.

**********

In one of the most famous scenes in The Godfather, Part II, the mob meets on a rooftop in Havana under the aegis of Hyman Roth, played by Lee Strasberg, who is supposed to represent mobster Meyer Lansky. Separate fact from fiction for us.

The movie is fictionalized but uses a lot of accurate historical detail. The rooftop scene shows Roth’s birthday party. They bring a cake out depicting the island of Cuba and cut it into pieces. It’s a powerful symbolic image, but the actual gathering of mob bosses from around the United States at the Hotel Nacional in Havana in 1946 was even more grandiose. It had been called by Meyer Lansky, the leader of the mob’s exploitation of Cuba in the 1950s, and it kicked off the era of entertainment and licentiousness Havana became known for. The mob funneled dirty money into Cuba to build casinos and hotels, which in turn generated the funds used to facilitate the corrupt political system led by President Fulgencio Batista.

You write, “It is impossible to tell the story of the Havana Mob without also chronicling the rise of Castro.” How closely were the two linked?

They weren’t directly linked. Castro was produced by many social conditions that existed in Cuba. But I think the mob became a symbol for the revolution of exploitation by outside forces, particularly the United States. Part of the narrative of the revolution was that the island was not able to control its own destiny and that all of the most valuable commodities were owned by corporations from the United States. In the eyes of Castro, the mob, the U.S. government, and U.S. corporations were all partners in the exploitation of Cuba.

Did mob bosses like Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky have bigger dreams for Cuba than just the creation of an enclave for gaming and leisure?

The idea was to create a criminal empire outside the United States where they had influence over local politics but could not be affected by U.S. law enforcement. They were exploring doing the same thing in the Dominican Republic and countries in South America. It was a grandiose dream. But the gangsters of that era, like Lansky, Luciano, and Santo Trafficante, saw themselves as CEOs of corporations, operating at an international level.

Several American icons come off pretty badly in your book—tell us about Frank Sinatra’s and John F. Kennedy’s involvement with the Havana mob.

Sinatra’s involvement with the mob in Havana is a subnarrative of his involvement with the mob in general, which was rooted in his upbringing in Hoboken, New Jersey. The mob is even rumored to have been instrumental in launching his career by financing his early development as a singer. He was very close to Lucky Luciano, who came from the same town in Sicily as Sinatra’s relatives and ancestors. Cuba was crucial because of the mob’s plan to create a chain of important hotels and nightclubs. Sinatra was going to be used as a lure to make it all happen. He was like the mob’s mascot in Havana.

Havana also became a destination for junkets, where politicians could do things they couldn’t in the United States. Sex was a big part of that. [While still serving in the Senate and before he was elected president], John F. Kennedy went down there with another young senator, from Florida, named George Smathers. Santo Trafficante, one of the leaders of the mob in Havana, later told his lawyer about how he had set up a tryst with three young Cuban prostitutes in a hotel room. What Kennedy didn’t know was that Santo Trafficante and an associate watched the orgy through a two-way mirror. Trafficante reportedly regretted not capturing it on film as a potential blackmail resource.

We can’t talk about Cuba in the ’50s without discussing the music scene, which you call “an international swirl of race, language, and class.” Put us on the dance floor.

The main dance style that hit that island was the mambo, created in the ’40s by a bandleader named Pérez Prado. It became a sensation in Cuba, Latin America, and the United States. It involved big orchestra music, and the dance moves were simple enough that the gringos could pick it up easily. Then there was rumba, which was a style of Cuban music rooted in the Santería religious culture. This exotic, sexy music drew celebrities like Marlon Brando and George Raft. Cuba also attracted great entertainers from the United States and Europe, like Nat King Cole, Eartha Kitt, and Dizzy Gillespie. I don’t think the mobsters anticipated that what they were doing would generate this exciting Afro-Cuban cultural explosion. But that’s what happened, and it became a major reason that Havana was such an exciting place in those years.

How did the revolution and the Cuban diaspora following the fall of Batista impact politics in the United States?

It was a hugely significant event, because it was the first time a country so close to the United States had achieved a successful socialist revolution. This set off a great deal of paranoia on the part of the U.S. government, which began to influence American politics. Cuba became a chess piece in the Cold War with the Soviet Union, inspiring the United States, particularly the CIA, to use the anti-Castro movement for all kinds of dirty politics and covert operations, like the Bay of Pigs invasion. Four of the five burglars in the Watergate break-in were also Cubans from Miami, who were talked into it by CIA agent E. Howard Hunt. Anti-Castro activists were manipulated by the right wing of the U.S. and the Republican Party for half a century.

You were recently in Cuba again. Does the mob era of the ’50s still have resonance?

The casinos are long since gone, but the hotels like the Nacional or Meyer Lansky’s Riviera are preserved in the exact same state they were in during the 1950s. The famous old American cars are still there too. You can go to Havana and walk the streets and still feel the ghosts of that history. It’s still very much alive.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.