This Mobster Museum Was Once One of New York City’s Most Notorious Speakeasies

See shell casings from Bonnie and Clyde’s final shoot out and John Dillinger’s death mask in the Museum of the American Gangster’s unusual collection

Within the walls of the American Gangster Museum at 80 St Mark’s Place in New York City’s East Village lies a bomb. Or, at least, there was at one point in recent history.

Back during the anarchic days of Prohibition, when this building was one of Manhattan’s most notorious speakeasies, its shadowy owner, Frank Hoffmann, wanted to make sure he could destroy any evidence of his crimes in a hurry.

“He’d take the tunnels, empty out the safe,” says the building’s owner, Lorcan Otway, as he gestures to where a passageway once stood. Otway tells Smithsonian.com that the same kind of explosive favored by Hoffmann was used in a bomb that exploded on Wall Street in 1920, killing 30 people and a horse.

The safe that once held the bomb is still there, tucked away in a corner of the basement. Now, it’s filled with empty beer bottles. At first glance, they might seem like holdovers from a cast party held by the occupants of the theater on the building’s ground floor. Until you notice the labels: They’re from the 1940s. The same bottles were in the safe when Otway’s father Howard opened it, in the early 1960s—along with $2 million in gold certificates and a photograph of a beautiful young woman.

For Otway, this story is personal. His father was what he describes as a “patsy” for the organized crime scene that dominated the East Village well into the 1960s. Hoffman had disappeared decades earlier, but Walter Schieb, Hoffman’s underling, was afraid of getting the money himself in case his boss decided to return. He coerced Howard, who had bought the building from him in 1964, into doing it instead. After Schieb left town to open a hotel in Florida, Otway’s father stayed, transforming the speakeasy’s old dance floor into the 80 St. Mark’s Theater.

The younger Otway grew up in the building and eventually traveled a few blocks west to NYU and a career as a lawyer. But the building beckoned, filled with unanswered questions. Why had Hoffman left so suddenly? How were Schieb and Hoffmann connected? Who was the woman in the photograph?

When the older Otway died in 1994, his son inherited the building and its mysteries. Slowly, his interest in the building turned into an obsession. He dug into newspaper archives and visited the offices of medical examiners. He memorized every newspaper article about Schieb and Hoffmann, every court date for every case Hoffmann could have been involved in, every advertisement in a 1930s broadsheet that he believes is the the key to the mysterious young woman. He finally identified her—he thinks the photo is of model and singer Ghia Ortega and that she was Hoffmann’s lover. For years, he’s worked on a history of Hoffmann, doggedly putting together piece after piece of evidence.

In 2010, Otway gave his obsession life. He transformed the ground floor apartment of 80 St. Mark’s Place into The Museum of the American Gangster, turning its two rooms into something that straddles the line between shrine and a forensic exhibition.

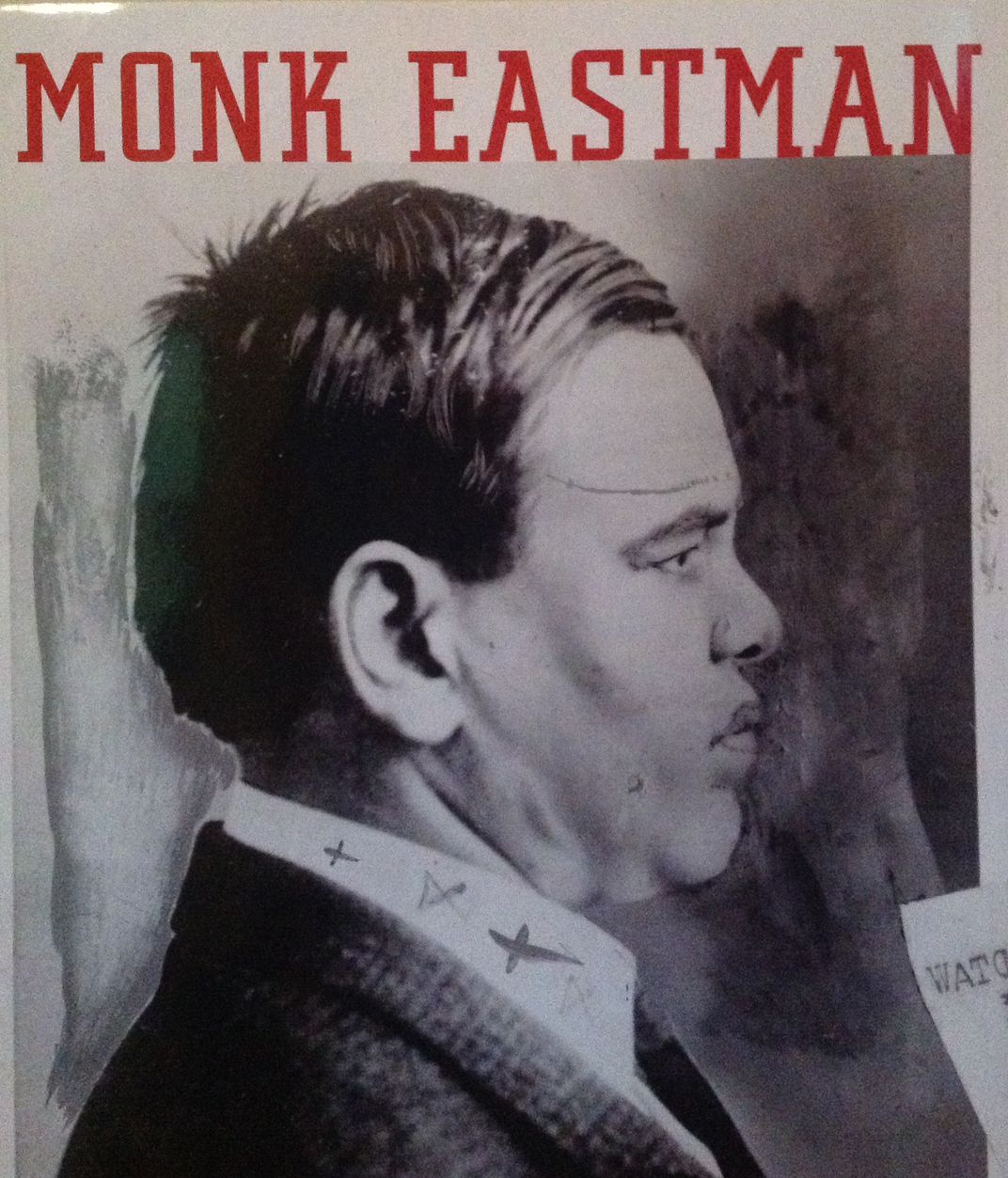

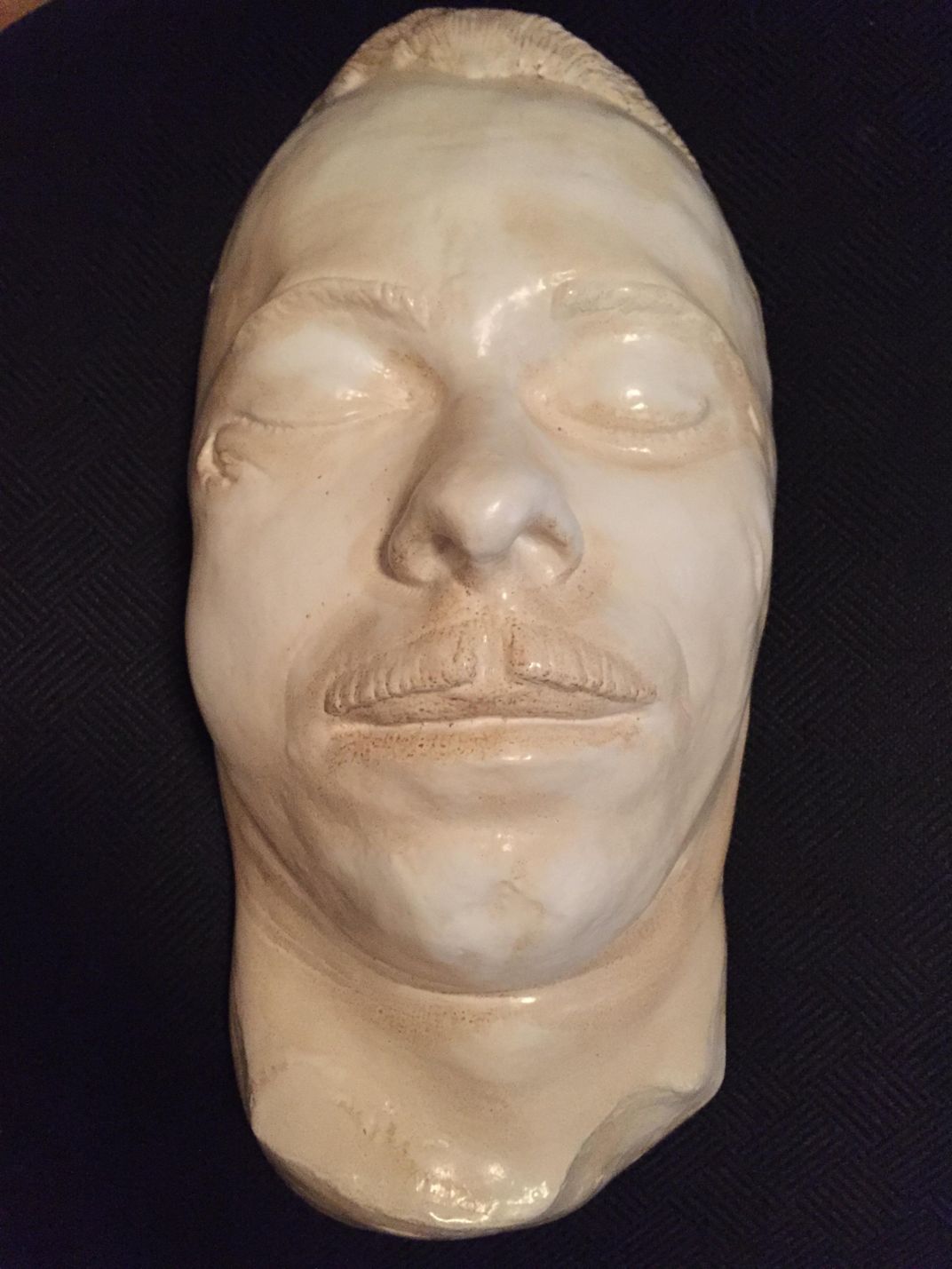

The collection is a personal one, painstakingly acquired from private collections. It includes reminders of the era’s biggest names, including shell casings from the final shootout of Bonnie and Clyde and the bullet that killed gangster “Pretty Boy” Floyd. It also holds two death masks of bank robber John Dillinger. Only a few castings have ever been made from the original molds. Otway theorizes that discrepancies in the features show that a decoy—possibly lookalike gangster Jimmy Lawrence, who disappeared around the same time— may have been killed in Dillinger’s place. (It is, of course, just a theory and most evidence point to the corpse being Dillinger.) Several items, including the bullets and death masks, come from the collection of researcher Neil Trickle, a ballistics expert who acquired them in turn from the estate of former Chicago medical examiner Clarence Goddard.

The museum also contains traces of Prohibition’s everyday participants, like Otway’s handmade model of The Black Duck, a smuggling ship used by rumrunners. The boat, he says, could outstrip law enforcement boats, helping its makers’ sons, brothers and cousins engage in the lucrative bootlegging trade. For Otway, the story of Prohibition is at its core a story of common people, like the ordinary young men and women drinking together in the museum’s display of candid Prohibition-era photographs.

The museum’s power, in Otway’s eyes, lies less in individual objects than in the story they present: one that goes beyond rakish gangsters and glamorous molls. It’s a narrative of an intricate and alternate, extra-governmental economy—and social order—that Otway sees as inseparable from American history as a whole.

“We’re caught between two concepts that make America what it is: moral certainty and liberty,” says Otway. America’s craving for moral order is in constant, dynamic tension with its desire to break its own laws “joyfully, defiantly,” says Otway—like the flappers and bootleggers did. Governmental crackdown and organized crime are, for Otway, two sides of the same coin.

He sees the world of smugglers, bootleggers, pirates and loan sharks as the story of “power on the margins”: Robin Hoods seizing opportunities from the wealthy. After all, Otway says, the Eighteenth Amendment, which prohibited the sale of liquor between 1920 and 1933, represented an “explosion of middle-class expectations.” For the first time, Otway says, one-fifth of the American economy was “released into illegality, into democratic anarchy.” A 1932 study estimated that Prohibition dodgers created up to $5 billion a year in economic activity—the equivalent of $64 billion today. It wasn’t a free market, says Otway, but rather a “direct-action free marketplace” where ordinary people could lay claim to a piece of the pie.

Sympathy for the criminal underworld might seem like a strange position for Otway, who is a committed Quaker, to take. But Otway finds plenty of parallels between his own Quaker tradition, with its emphasis on civil disobedience, and the community structure of organized crime. “We Quakers are much more organized crime than organized faith,” he laughs. “Very little we do we do efficiently. Except break the law.”

Otway isn’t alone in this interpretation of organized crime in American society. Harvard sociologist Daniel Bell coined the term “the queer ladder of social mobility” to describe the phenomenon. This “queer ladder,” said Bell, was a way people could advance outside of the white, Protestant cultural mainstream. For Bell, organized crime had a “functional role” in society.

People didn’t just progress up that “queer ladder” during the Prohibition years. “When my family first moved to this neighborhood in 1964,” Otway recalls, “every single building on the block was occupied by a family who lived and worked in the building, none of whom would be easily granted bank loans.” Unable to get credit, middle-class families might instead make deals with the Mob. Otway argues out that, for certain ethnic minorities, organized crime was sometimes the only way to gain economic mobility. “It wasn’t a glass ceiling,” he says, “but a brick wall.”

But that mobility came at a very real cost. Among the museum’s holdings is a newspaper article about the notorious 1929 Saint Valentine’s Day Massacre, in which seven Chicago gangsters were executed by Al Capone’s forces. Brutal violence—both within and between gangs—was common in an industry where gangsters’ legitimacy was inseparable from the fear they inspired.

Rival criminals weren’t the only people who feared for their lives: If small business owners failed to pay “protection money” to the mobsters who controlled their respective areas, they could face fatal consequences from men like Jimmy “the Bomber” Belcastro, a Capone crony known for planting improvised explosive devices in Chicago restaurants and saloons. Still, the shadowy nature of organized crime makes exact statistics about its impact—and death toll—difficult to obtain.

Otway sees organized crime as a buffer against corporate greed—and against the violence of the government’s relentless fight to root out vice. The museum contains an example of the hideously dangerous 12-gauge Mansville machine gun—popular among policemen cracking down on bootleggers and virtually impossible to fire less than thrice. Also on view are canisters of the legal industrial alcohol the government intentionally poisoned to discourage consumption. “Ten thousand people died drinking that,” Otway claims. Despite urban legends about “bathtub gin” causing blindness and other ailments, he says, the “legal” stuff, like wood alcohol, often proved more noxious.

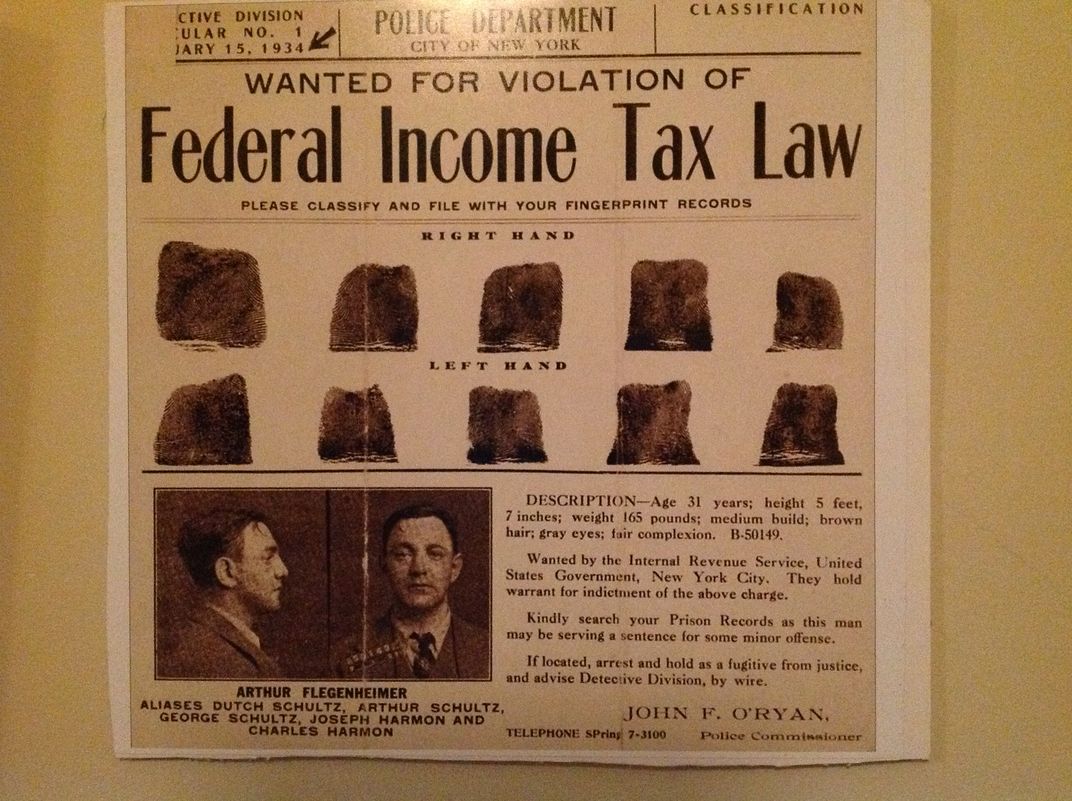

Otway hopes that his collection of artifacts will instill visitors with an appreciation of a counter-narrative in American history: the story of people who, in their own way, challenged existing structures of class, money and race. Among their ranks were second-generation Italian immigrants like Al Capone, Jewish mobsters like Murder Inc.’s Dutch Schultz and Meyer Lansky, and African-American mobsters like Casper Holstein and Stephanie St. Clair—gangsters Otway claims provided their respective ethnic communities with organizational structures outside the government-sanctioned mainstream.

Today, the Museum of the American Gangster receives a slow stream of visitors. Some are attracted to the glamor of Prohibition, others to the sensationalism and “guts” of the period. Is the legacy of the American gangster heroic or just sordid? Either way, the American obsession with the era’s underbelly is as alive as a bomb in a gangster’s basement.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.