Mt. Rushmore

With a Native American superintendent, the South Dakota monument is becoming much more than a shrine to four presidents.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/rushmore_main_388.jpg)

Blame it on Cary Grant. The climactic chase in Hitchcock’s 1959 thriller North by Northwest, in which he and Eva Marie Saint are pursued by foreign spies around the faces of George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt, is what fixed the idea in tourists’ imaginations. Today the first question out of many visitors’ mouths is not why, or even how, Mount Rushmore was carved, but can they climb it. Actually, it’s not such a far-fetched question. Sculptor Gutzon Borglum’s 1935 conception for the monument called for a grand public stairway leading from the base of the mountain to a hall of records, behind the presidential heads. But when the artist ran out of quality granite, and the project ran out of money, the plan was shelved. Climbing on the memorial has been officially prohibited since work ended there in 1941. In fact, even Hitchcock had to shoot his famous chase scene on a replica built in a Hollywood studio.

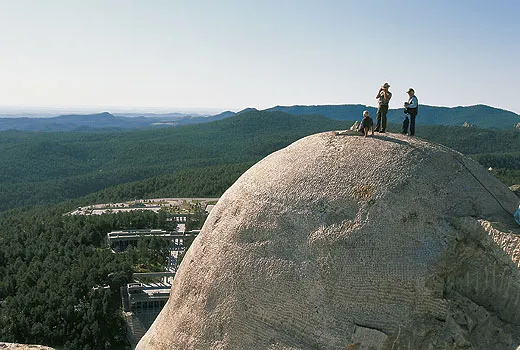

Which is why a special invitation from the park superintendent to “summit” Mount Rushmore is not something one can easily turn down. Early one morning, I and several other lucky hikers silently followed park ranger Darrin Oestmann on a trail through a sweetly scented ponderosa forest in the Black Hills of South Dakota, listening to birdsong and the cracking of twigs from passing goats. Scattered along the path were rusting nails, wires and lengths of air compression pipes, all left by the 400 or so local laborers who from 1927 to 1941 followed this very route, by wooden stairs, on their Promethean task.

Oestmann paused to point out a rarely glimpsed view of George Washington’s profile, gleaming in the morning light. Mount Rushmore has not looked so good in more than six decades. This past summer, the four presidents were given a high-tech face-lift; they were blasted with 150-degree water under high pressure. Sixty-four years’ worth of dirt and lichens fell from the memorial. “Now the faces are whiter and a lot shinier,” said Oestmann, who helped clean “about three quarters of the first president. You see that dot in Washington’s left eyelid?” He pointed to a broken drill bit stuck in the stone. “You could hardly see that before.”

About ten minutes later, we scrambled up a few steep boulders and squeezed through pine branches, then passed beyond a high-security fence. Near-vertical metal steps took us into a granite crevice that runs behind the presidential heads—an oblong sliver, looking like the secret entrance to a pharaoh’s tomb. This, we are told, is the Hall of Records, the vault Borglum envisioned. The hall was to be a repository for the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Worried that generations from now people might find Mount Rushmore as enigmatic as Stonehenge, the sculptor also wanted to store information about the four presidents, as well as a record of American history and an explanation of, as he put it, “how the memorial was built and frankly, why.”

The vault was never finished. Today, it’s an ever-narrowing passage, honeycombed with drill marks, that stretches about 80 feet into the rock. Still, in 1998, Borglum’s wish was partly fulfilled when the park service placed a teak box in a titanium cast in a hole they drilled at the hall’s entrance. The box contained 16 porcelain panels covered with historical data, including a biography of the artist and his struggles to carve the memorial.

But the highpoint of the climb was yet to come. As Oestmann led us up the last steep stairway, we burst from the shadows into brilliant sunshine—on top of George Washington’s head, 500 feet above the visitor center and 5,725 feet above sea level. As I wandered jelly-kneed over to Jefferson’s and Lincoln’s white pates—thankfully, their tops are relatively flat—the exhilarating view across the craggy, pine-covered Black Hills seemed never-ending.

Gutzon Borglum first stood on this spot in August 1925, when the memorial was still a half-formed dream. The idea for a titanic public sculpture came from South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson, who hoped it would lure more tourists—and their dollars—to the remote and impoverished state. The Black Hills, which boasted some of South Dakota’s most spectacular scenery, were the obvious location, and in mid-1924 Robinson invited Borglum, one of America’s leading sculptors, to create it. It was a fortuitous choice: he was an obsessive artist and consummate showman, by turns inspired, energetic, egotistical and abrasive, who despite his success (he was one of the first American sculptors to have work—two pieces—purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) still yearned for a project that would earn him immortality.

Dismissing Robinson’s idea that the sculpture should feature Western heroes such as Lewis and Clark, Chief Red Cloud and Buffalo Bill, Borglum decided to carve the presidents, and he arrived in Rapid City with great fanfare that summer to search the rugged landscape for the optimal site. The cliff-face of Mount Rushmore seemed to offer the best granite and the best setting: a sunny, eastern exposure. In mid-August 1925, the sculptor, his 13-year-old son, Lincoln, and Robinson traveled with a local guide on horseback to the mountain to climb it to get a closer look. Standing on the summit, Borglum gazed out on the Black Hills and seemed—if only for a moment—humbled by the undertaking.

“I was conscious we were in another world...,” Borglum later wrote. “And there a new thought seized me...the scale of that mountain peak.... It came over me in an almost terrifying manner that I had never sensed what I was planning.” At age 58 the artist was contemplating a work nearly as ambitious as the ancient Colossus of Rhodes without any secure source of funding in a location unreachable by road. Its creation would be an epic battle, not only against nature, but against government agencies controlling the purse strings.

Oestmann calls our attention to red plotting points around Lincoln’s eyes and green numbers along his hairline—revealed during preparation for the memorial’s cleaning. He offers to take my photograph perched on Jefferson. “Don’t go any farther back,” he warns, as I maneuver cautiously into position.

Mount Rushmore might seem the most immutable of America’s historical monuments. After all, what can possibly change on those stone faces, which seem to gaze down indifferently on the follies of their countrymen? Quite a lot, as it happens—including a seismic cultural shift traceable to the appointment, in 2004, of Gerard Baker, Mount Rushmore’s first American Indian superintendent. Baker, 52, a Mandan-Hidatsa raised on the Fort Berthold Reservation in western North Dakota, has begun to expand programs and lectures at the monument to include the Indian perspective. Until recently, visitors learned about Rushmore as a patriotic symbol, as a work of art or as a geological formation, but nothing about its pre-white history—or why it raises such bitterness among many Native Americans.

“A lot of Indian people look at Mount Rushmore as a symbol of what white people did to this country when they arrived—took the land from the Indians and desecrated it,” Baker says. “I’m not going to concentrate on that. But there is a huge need for Anglo-Americans to understand the Black Hills before the arrival of the white men. We need to talk about the first 150 years of America and what that means.”

Indeed, Borglum erected his “shrine of democracy” on sanctified ground. Paha Sapa, meaning Black Hills in Lakota, were—and remain—a sacred landscape to many Indian nations, some of whom regard them as the center of the world. Natural formations such as Bear Butte and the Devil’s Tower (over the border in Wyoming) are the setting for prayers, vision quests and healing ceremonies, while Wind Cave, a vast underground complex of limestone tunnels, is revered as the place where the Lakota emerged from the underworld to earth. Under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, Congress confirmed that the area would remain inviolate as the core of the Greater Sioux Reservation. But only six years later, in 1874, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered a military “reconnaissance” of the Black Hills, possibly because of rumors of gold in the mountains. He put the operation under the command of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer. In July 1874, Custer led a small army of more than 1,000 men, including cavalry and infantry, Indian scouts, interpreters, guides and civilian scientists, into the region with over 100 canvas wagons, 3 Gatling guns and a cannon.

This formidable group behaved, in the words of author Evan S. Connell, “less like a military reconnaissance than a summer excursion through the Catskills.” According to surviving letters and diaries, the men were bewitched by the Black Hills’ beauty. These mountains, some of the oldest in North America, and their pine-filled valleys form a verdant oasis in the Great Plains. In the summer of 1874, crusty cavalrymen would lean from their horses to pluck bouquets of wildflowers, and officers enjoyed champagne and wild gooseberries while the enlisted men played baseball. Custer expanded his natural history collection, loading a cart full of rare toads, petrified wood and rattlesnakes. “The air is serene and the sun is shining in all its glory,” wrote Lt. James Calhoun, one of Custer’s officers, in his diary. “The birds are singing sweetly, warbling their sweet notes as they soar aloft. Nature seems to smile on our movement.”

But for the Lakota families who watched the group from the surrounding hilltops, the expedition foretold disaster. Custer’s prospectors discovered gold in the mountains, and soon a rush to the Black Hills was on, with Deadwood, in the northern part of the region, one of the first illegal settlements. President Grant sent envoys to buy the Black Hills, but the Lakota refused to bargain: Lakota chief Sitting Bull said he would not sell so much as a pinch of dust. In the Great Sioux War that broke out in 1876 between the United States and a combined force of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, many of the cavalrymen who had plucked the Black Hills’ flowers would lose their lives on the Little Bighorn in Montana—including Custer and Calhoun. The Lakota, however, were soon defeated, and, in 1877, Congress passed an act requiring them to relinquish their land and stay on reservations.

When Borglum arrived half a century later, the events leading up to the Indian Wars in the Black Hills were still fresh in many people’s minds—Indians and whites. Yet few of Rushmore’s planners seemed to have considered how the Native Americans might feel about the monument.

Several days following my tour of Rushmore, I visited the Defenders of the Black Hills, a Native American group that meets regularly in a Rapid City community center to inveigh against what they consider environmental affronts still scarring their lands, such as runoff from abandoned uranium mines, logging, drilling by mining companies, and the dumping of toxic waste. When I explained to the dozen men and women there—mostly Lakota, but also Ponca and Northern Cheyenne—that I was writing about the Mount Rushmore memorial, they laughed, then turned angry.

“Tell your readers that we’d like to blow it up!” said one.

“Cover those white faces up!”

“They call them the founding fathers? To us, they’re the founding terrorists!”

The coordinator, a diminutive woman in her 50s named Charmaine White Face, a Lakota, spoke matter-of-factly. “We all hate Mount Rushmore,” she said. “It’s a sacred mountain that has been desecrated. It’s like a slap in the face to us—salt in the wounds—as if a statue of Adolf Hitler was put up in the middle of Jerusalem.”

She handed me a badge: “The Black Hills Are Not For Sale,” it read, referring to a 1980 court ruling that awarded the Sioux more than $100 million for the loss of the Hills. Though their communities remain desperately poor, the Lakota have refused the money, which has grown with interest to well over $500 million.

When I relay my encounter with the Defenders to Baker later, he smiles. “Hell, Indians are always telling me to blow up Mount Rushmore, but they know that’s not going to happen.” Sure, he says, the Black Hills were stolen from the Indians. “That’s a historical fact. But we’re not here at Mount Rushmore just to talk about broken treaties or make people feel guilty. The Defenders have a cause, and it’s a good cause. But we’re here at Mount Rushmore to educate.”

Judy Olson, chief of interpretation at Mount Rushmore, says that there has been a strong positive response among Anglo visitors to new programs and exhibits that Baker has initiated, including a tepee manned by Lakota families. “We have four white guys up there. They represent the first century and a half of U.S. history. But there’s a larger story to talk about. Who were the people here in the Black Hills before that? To broaden the old themes, to bring in other cultures, to include the good and the bad of American history, is what people want and need.”

Crazy Horse Rides Again

“Fire in the hole! Fire in the hole! Fire in the hole!”

As the voice rings out, all eyes are fixed on a scarred mountainside where the enormous head and torso of the Lakota chief Crazy Horse can be clearly made out. He sits on horseback, his arm pointing toward the horizon. Then a dynamite blast tears the silence, sending a shower of granite boulders thundering to earth; the huge charge, one of two or three every week in summer, makes barely a dent in the neck of the warrior’s horse.

Only 15 miles from Mount Rushmore, a monolithic new image is emerging from the Black Hills granite: a 563-foot-tall sculpture of the famous Native American who defeated Custer at Little Bighorn in 1876. Today a visit to the site testifies to the growing interest in Native American themes: even as a work in progress, Crazy Horse has already become a must-see counterpart to Mount Rushmore, luring more than one million visitors last year. (Rushmore had three million.)

Its scale is mind-boggling. When finished, the sculpture will be the world’s largest mountain carving—dwarfing such monuments as the Great Pyramid of Giza and the Statue of Liberty. In fact, all four of Rushmore’s presidents will fit inside Crazy Horse’s 87.5-foot-tall head. The memorial depicts Crazy Horse responding to a taunt from a white trader before his death in 1877. Asked what had become of his lands, he replied: “My lands are where my dead lie buried.”

The new monument was conceived in the late 1930s by Chief Henry Standing Bear, a Lakota. As Mount Rushmore neared completion, he wrote that he wanted to show the world that “the red man has great heroes, too.” In 1939, the chief invited a muscular Boston sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski, to undertake a sculpture of Crazy Horse. After serving in the Army in World War II, Ziolkowski leased a vast chunk of the Black Hills and started work on the monolith in 1948. “Every man has his mountain,” he said at the time. “I’m carving mine!” In the late 1970s, looking like a latter-day Walt Whitman, with a huge white beard and a broad-rimmed hat, his wife and ten children laboring away at his side, he was still carving. Perhaps mindful of Borglum’s years of wrangling with bureaucrats, Ziolkowski refused to let the U.S. government become involved in the project, twice turning down grants of $10 million. Instead, he funded the project with private donations and contributions from visitors. This meant that progress was slow. When Ziolkowski died in 1982, the sculpture was only a vague outline; many locals assumed it would be abandoned.

But Ziolkowski’s family rallied to continue the work. In 1998, Crazy Horse’s completed face was unveiled, creating the sort of publicity that Borglum had enjoyed in 1930 when he revealed his first finished image, of Washington. Seemingly overnight, a chimerical project had become real, bringing streams of tourists intent upon learning more about Indian history. In 2000, a cathedral-like visitor center opened at the memorial, with a museum, Native American cultural center, and cinema. Plans also include a university and medical training center for Native Americans.

When might the monolith be finished? “There’s no way to estimate,” says Ruth Ziolkowski, the sculptor’s widow, who is nearly 80 and CEO and president of the nonprofit Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation. “It would be nothing but a wild guess anyway. We’re not trying to be difficult. We just don’t know. Korczak always said it wasn’t important when it was finished as long as it was done right.”

The carving is now overseen by Korczak’s eldest son, Casimir, 52, who learned his skills on the rock-face with his father. “He was one of a kind, that’s for sure,” he says with a laugh. “We had our fights, like every father and son.”

“Only in America could a man carve a mountain,” Ziolkowski once declared—a sentiment that has not won over the Defenders of the Black Hills. They’re not fans of this monument and say that it is as much of an environmental and spiritual violation of the Native lands as Borglum’s work on Rushmore. Charmaine White Face, the Defenders’ chairperson, says all work on Crazy Horse should cease at once: “Let nature reclaim the mountain!”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)