Muskrat Love

An annual festival on Maryland’s Eastern Shore celebrates an unlikely mascot

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/muskrat-631.jpg)

Late winter on the marshes of Maryland's Eastern Shore is a soggy affair. Fog hides the stands of loblolly pines—practically the only green things growing at this time of year—and in the rain even the great blue heron looks a bit bedraggled.

It's muskrat weather. And muskrat—baked, stewed and microwaved—is what's for dinner at this K-8 school way out in the wetlands of Golden Hill. Here local watermen have gathered, as they always do on the last weekend in February, for an amalgam of sporting contests and snacking opportunities billed, rather grandly, as The National Outdoor Show.

With the muskrat cook-off just moments away, Marlene Meninger's muskrat potato skins are brown and crisp, though her muskrat jambalaya is still simmering.

"Oh, I'm stressing," she says, fanning her hands over a crockpot as though it had fainted.

The annual festival traces its roots back to the Great Depression, when muskrat pelts were the mainstay of the winter economy here, after blue crab season ended and the marshes froze. Fathers and sons trap them still, and for pin-prick communities along the Chesapeake Bay, the muskrat remains an unofficial mascot. Portraits of the buck-toothed, retiring rodents are everywhere at the show. There are muskrat messenger bags and mouse pads for sale, and a silver muskrat charm bracelet will be raffled off later on. A portion of the festival's proceeds are invested back into the community. "Other places have zucchini festivals," explains Thomas Miller, a park ranger with the nearby Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. "Well, we have the muskrat."

To outsiders, the show's most controversial component is the World Championship Muskrat Skinning Contest, a gruesome yet oddly engrossing race held on the auditorium stage. Filet knives swoop as the region's best trappers wrestle with the rabbit-sized pelts. (At this year's "Miss Outdoors" pageant, another festival highlight, one aspiring beauty queen skinned a "rat" as her talent, to thunderous applause) Locals, though, are more likely to argue about the cooking competition. Old-timers claim that, doctored right, dark, pungent muskrat meat can taste just like roast beef, but teenagers are skeptical.

Often stewed with onions and sage to kill the "marsh mud" flavor, muskrat used to be a dietary staple here. A generation ago, Eastern Shore families in the fur trade might eat wild game six nights a week and chicken on Sundays. But pelt prices plummeted in the 1980s, and these days trapping muskrat is hardly worth the trouble. Besides, the region is changing: Maryland's once-isolated fishing villages are much more closely linked to the outside world and its Burger Kings.

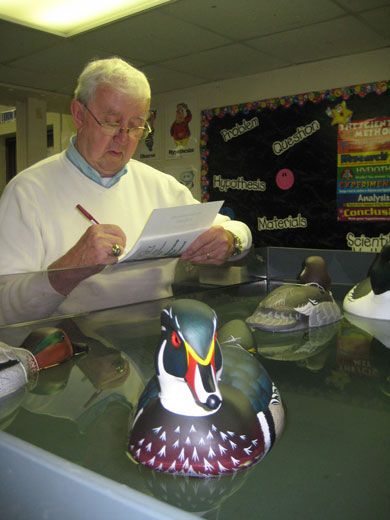

Even families who have moved away still try to make it to the outdoor show each year, to honor the old ways, and, naturally, the muskrat. The show pays homage to other local critters: master carvers coax exquisite swans out of hunks of wood, there's an oyster-shucking showdown, and young boys blow geese calls with the intensity of great saxophonists. Yet it's the lowly muskrat whose likeness tops the trophies, even though he is at the very bottom of the marsh hierarchy. Despite webbed hind feet and a tail like a rudder, the rodent often falls prey to herons, foxes and snapping turtles; whole muskrat traps are sometimes found inside the nests of bald eagles, a species that has rebounded here in recent years. But the watermen dismiss the imposing birds as "white-headed buzzards" and instead embrace the bewhiskered creatures whose tunnels criss-cross the earth beneath the cattails and tall grasses, underlying and connecting everything, like the tangled local bloodlines that only the natives understand.

Above all, watermen say, the festival is an excuse to don hip boots and gunning jackets and tramp out to the marshes again. There they experience what the rest of us miss: the sight of eagles warring, the sparrow's song, and the scream of the otter, which sounds so exactly like a baby's cry that it stops the most seasoned trappers in their tracks every time.

Solemn judges arrive at the cooking competition and close the door. They emerge a long time later, smacking their lips dramatically. Marlene's jambalaya takes the $25 prize. She's not completely surprised; her muskrat enchiladas won first place last year.

Along with some very mysterious spices, her secret is this: she doesn't like muskrat meat herself. An administrative assistant at a nearby police station, she entered the contest a few years ago because participation was dwindling, and she hated to think of the tradition dying out.

Chances are it won't. As old folks retire from running the show, children and grandchildren take their places, along with newcomers to the area who've gotten the "mud between their toes." Everyone seems to want the local beauty queen to carry a filet knife as gracefully as a long-stemmed rose, and for little boys to aspire to be World Champion Muskrat Skinners.

The muskrat, too, is a survivor. He's outlasted centuries of trapping, nutria invasions, the eagle's comeback—even the fires that people set every winter in the marshes, which clear the way for new grass come spring.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.