Myanmar’s Young Artists and Activists

In the country formerly known as Burma, these free thinkers are a force in the struggle for democracy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Myanmar-Free-Thinkers-Rapper-J-Me-graffiti-art-show-631.jpg)

Editor's Note, April 3, 2012: The election of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi—the face of her nation’s pro-democracy movement—to Parliament opens a dramatic new chapter in Burma’s journey from oppressive military rule. Her supporters, from young artists seeking freedom of expression, to a generation of activists long committed to the struggle against the ruling generals—believe that a sea change is overtaking their society. We wrote about her supporters in March 2011.

The New Zero Gallery and Art Studio looks out over a scruffy street of coconut palms, noodle stalls and cybercafés in Yangon (Rangoon), the capital of Myanmar, the Southeast Asian country formerly known as Burma. The two-story space is filled with easels, dripping brushes and half-finished canvases covered with swirls of paint. A framed photograph of Aung San Suu Kyi, the Burmese opposition leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who was released from seven years of house arrest this past November, provides the only hint of the gallery’s political sympathies.

An assistant with spiky, dyed orange hair leads me upstairs to a loft space, where half a dozen young men and women are smoking and drinking coffee. They tell me they’re planning an “underground” performance for the coming week. Yangon’s tiny avant-garde community has been putting on secret exhibitions in spaces hidden throughout this decrepit city—in violation of the censorship laws that require every piece of art to be vetted for subversive content by a panel of “experts.”

“We have to be extremely cautious,” says Zoncy, a diminutive 24-year-old woman who paints at the studio. “We are always aware of the danger of spies.”

Because their work is not considered overtly political, Zoncy and a few other New Zero artists have been allowed to travel abroad. In the past two years, she has visited Thailand, Japan and Indonesia on artistic fellowships—and come away with an exhilarating sense of freedom that has permeated her art. On a computer, she shows me videos she made for a recent government-sanctioned exhibition. One shows a young boy playing cymbals on a sidewalk beside a plastic doll’s decapitated head. “One censor said [the head] might be seen as symbolizing Aung San Suu Kyi and demanded that I blot out the image of the head,” Zoncy said. (She decided to withdraw the video.) Another video consists of a montage of dogs, cats, gerbils and other animals pacing around in cages. The symbolism is hard to miss. “They did not allow this to be presented at all,” she says.

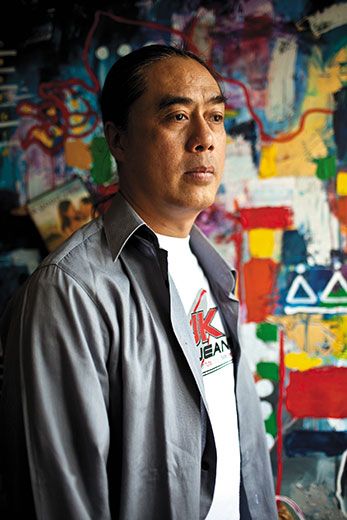

The founder and director of the New Zero Gallery is a ponytailed man named Ay Ko, who is dressed on this day in jeans, sandals and a University of California football T-shirt. Ay Ko, 47, spent four years in a Myanmar prison following a student uprising in August 1988. After he was released, he turned to making political art—challenging the regime in subtle ways, communicating his defiance to a small group of like-minded artists, students and political progressives. “We are always walking on a tightrope here,” he told me in painstaking English. “The government is looking at us all the time. We [celebrate] the open mind, we organize the young generation, and they don’t like it.” Many of Ay Ko’s friends and colleagues, as well as two siblings, have left Myanmar. “I don’t want to live in an abroad country,” he says. “My history is here.”

Myanmar’s history has been turbulent and bloody. This tropical nation, a former British colony, has long worn two faces. Tourists encounter a land of lush jungles, golden pagodas and monasteries where nearly every Burmese is obliged to spend part of one year in serene contemplation. At the same time, the nation is one of the world’s most repressive and isolated states; since a military coup in 1962, it has been ruled by a cabal of generals who have ruthlessly stamped out dissent. Government troops, according to witnesses, shot and killed thousands of students and other protesters during the 1988 rebellion; since then, the generals have intermittently shuttered universities, imprisoned thousands of people because of their political beliefs and activity, and imposed some of the harshest censorship laws in the world.

In 1990, the regime refused to accept the results of national elections won by the National League for Democracy (NLD) Party led by Aung San Suu Kyi—the charismatic daughter of Aung San, a nationalist who negotiated Myanmar’s independence from Britain after World War II. He was killed at age 32 in 1947, by a hit squad loyal to a political rival. Anticipating the victory of Suu Kyi’s party, the junta had placed her under house arrest in 1989; she would remain in detention for 15 of the next 21 years. In response, the United States and Europe imposed economic sanctions that include freezing the regime’s assets abroad and blocking nearly all foreign investment. Cut off from the West, Myanmar—the military regime changed the name in 1989, though the U.S. State Department and others continue to call it Burma—fell into isolation and decrepitude: today, it is the second-poorest nation in Asia, after Afghanistan, with a per capita income of $469 a year. (China has partnered with the regime to exploit the country’s natural gas, teak forests and jade deposits, but the money has mostly benefited the military elite and their cronies.)

The younger generation has been particularly hard hit, what with the imprisonment and killing of students and the collapse of the education system. Then, in September 2007, soldiers shot and beat hundreds of young Buddhist monks and students marching for democracy in Yangon—quelling what was called the Saffron Revolution. Scenes of the violence were captured on cellphone video cameras and quickly beamed around the world. “The Burmese people deserve better. They deserve to be able to live in freedom, just as everyone does,” then Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice said in late September of that year, speaking at the United Nations. “The brutality of this regime is well known.”

Now a new generation of Burmese is testing the limits of government repression, experimenting with new ways of defying the dictatorship. The pro-democracy movement has taken on many forms. Rap musicians and artists slip allusions to drugs, politics and sex past Myanmar’s censors. Last year, a subversive art network known as Generation Wave, whose 50 members are all under age 30, used street art, hip-hop music and poetry to express their dissatisfaction with the regime. Members smuggled underground-music CDs into the country and created graffiti insulting Gen. Than Shwe, the country’s 78-year-old dictator, and calling for Suu Kyi’s release. Half the Generation Wave membership was jailed as a result. Young bloggers, deep underground, are providing reportage to anti-regime publications and Web sites, such as Irrawaddy Weekly and Mizzima News, put out by Burmese exiles. The junta has banned these outlets and tries to block access to them inside the country.

Young activists have also called attention to the dictatorship’s lack of response to human suffering. According to the British-based human rights group Burma Campaign, the Burmese government abandoned victims of the devastating 2008 cyclone that killed more than 138,000 people and has allowed thousands to go untreated for HIV and AIDS. (Although more than 50 international relief organizations work in Myanmar, foreign donors tend to be chary with humanitarian aid, fearing that it will end up lining the pockets of the generals.) Activists have distributed food and supplies to cyclone victims and the destitute and opened Myanmar’s only private HIV-AIDS facility, 379 Gayha (Gayha means shelter house; the street number is 379). The government has repeatedly tried to shut the clinic down but has backed off in the face of neighborhood protests and occasional international press attention.

It’s not quite a youth revolution, as some have dubbed it—more like a sustained protest carried out by a growing number of courageous individuals. “Our country has the second-worst dictatorship in the world, after North Korea,” said Thxa Soe, 30, a London-educated Burmese rapper who has gained a large following. “We can’t sit around and silently accept things as they are.”

Some in Myanmar believe they now have the best chance for reform in decades. This past November, the country held its first election since 1990, a carefully scripted affair that grafted a civilian facade onto the military dictatorship. The regime-sponsored party captured 78 percent of the vote, thus guaranteeing itself near-absolute power for another five years. Many Western diplomats denounced the result as a farce. But six days later, The Lady, as her millions of supporters call Suu Kyi, was set free. “They presumed she was a spent force, that all of those years of being in confinement had reduced her aura,” says a Western diplomat in Yangon. Instead, Suu Kyi quickly buoyed her supporters with a pledge to resume the struggle for democracy, and exhorted the “younger generation” to lead the way. Myanmar’s youth, she told me in an interview at her party headquarters this past December, holds the key to transforming the country. “There are new openings, and people’s perceptions have changed,” she said. “People will no longer submit and accept everything the [regime says] as the truth.”

I first visited Myanmar during a post-college backpacking trip through Asia in 1980. On a hot and humid night, I took a taxi from the airport through total darkness to downtown Yangon, a slum of decaying British-colonial buildings and vintage automobiles rumbling down potholed roads. Even limited television broadcasts in Myanmar were still a year away. The country felt like a vast time warp, entirely shut off from Western influence.

Thirty years later, when I returned to the country—traveling on a tourist visa—I found that Myanmar has joined the modern world. Chinese businessmen and other Asian investors have poured money into hotels, restaurants and other real estate. Down the road from my faux-colonial hotel, the Savoy, I passed sushi bars, trattorias and a Starbucks knockoff where young Burmese fire text messages to one another over bran muffins and latte macchiatos. Despite efforts by the regime to restrict Internet use (and shut it down completely in times of crisis), young people crowd the city’s many cybercafés, trading information over Facebook, watching YouTube and reading about their country on a host of political Web sites. Satellite dishes have sprouted like mushrooms from the rooftop of nearly every apartment building; for customers unable or unwilling to pay fees, the dishes can be bought in the markets of Yangon and Mandalay and installed with a small bribe. “As long as you watch in your own home, nobody bothers you,” I was told by my translator, a 40-year-old former student activist I’ll call Win Win, an avid watcher of the Democratic Voice of Burma, a satellite TV channel produced by Burmese exiles in Norway, as well as the BBC and Voice of America. Win Win and his friends pass around pirated DVDs of documentaries such as Burma VJ, an Academy Award-nominated account of the 2007 protests, and CDs of subversive rock music recorded in secret studios in Myanmar.

After a few days in Yangon, I flew to Mandalay, Myanmar’s second-largest city, to see a live performance by J-Me, one of the country’s most popular rap musicians and the star attraction at a promotional event for Now, a fashion and culture magazine. Five hundred young Burmese, many wearing “I Love Now” T-shirts, packed a Mandalay hotel ballroom festooned with yellow bunting and illuminated by strobe lights.

Hotel employees were handing out copies of the Myanmar Times, a largely apolitical English-language weekly filled with bland headlines: “Prominent Monk Helps Upgrade Toilets at Monasteries,” “Election Turnout Higher Than in 1990.” In a sign of the slightly more liberal times, the paper did carry a photograph inside of Suu Kyi, embracing her younger son, Kim Aris, 33, at Myanmar’s Yangon International Airport in late November—their first meeting in ten years. Suu Kyi was married to British academic Michael Aris, who died of cancer in 1999; he failed to gain permission to visit his wife during his final days. The couple’s older son, Alexander Aris, 37, lives in England.

At the hotel, a dozen Burmese fashion models ambled down a catwalk before J-Me leapt onto the stage wearing sunglasses and a black leather jacket. The tousle-haired 25-year-old rapped in Burmese about love, sex and ambition. In one song, he described “a young guy in downtown Rangoon” who “wants to be somebody. He’s reading English language magazines, looking inside, pasting the photos on his wall of the heroes he wants to be.”

The son of a half-Irish mother and a Burmese father, J-Me avoids criticizing the regime directly. “I got nothing on my joint that spits against anyone,” the baby-faced rapper told me, falling into hip-hop vernacular. “I’m not lying, I’m real. I rap about self-awareness, partying, going out, spending money, the youth that’s struggling to come up and be successful in the game.” He said his songs reflect the concerns of Myanmar’s younger generation. “Maybe some kids are patriotic, saying, ‘Aung San Suu Kyi is out of jail, let’s go down and see her.’ But mostly they’re thinking about getting out of Burma, going to school abroad.”

Not every rapper treads as carefully as J-Me. Thxa Soe needles the regime from a recording studio in a dilapidated apartment block in Yangon. “I know you’re lying, I know you’re smiling, but your smile is lying,” he says in one song. In another, titled “Buddha Doesn’t Like Your Behavior,” he warns: “If you behave like that, it’s gonna come back to you one day.” When I caught up with him, he was rehearsing for a Christmas Day concert with J-Me and a dozen other musicians and preparing for another battle with the censors. “I have a history of politics, that’s why they watch me and ban so many things,” the chunky 30-year-old told me.

Thxa Soe grew up steeped in opposition politics: his father, a member of Suu Kyi’s NLD Party, has been repeatedly jailed for participating in protests and calling for political reform. One uncle fled the country in 2006; a cousin was arrested during student protests in the 1990s and was put in prison for five years. “He was tortured, he has brain damage, and he can’t work,” Thxa Soe said. His musical awakening came in the early 1990s, when a friend in Myanmar’s merchant marine smuggled him cassettes of Vanilla Ice and M.C. Hammer. Later, his father installed a satellite dish on their roof; Thxa Soe spent hours a day glued to MTV. During his four years as a student at London’s School of Audio Engineering, he says, “I got a feeling about democracy, about freedom of speech.” He cut his first album in 2000 and has tangled with censors ever since. Last year, the government banned all 12 tracks on his live-concert album and an accompanying video that took him a year to produce; officials claimed he showed contempt for “traditional Burmese music” by mixing it up with hip-hop.

During a recent trip to New York City, Thxa Soe participated in a benefit concert performed before hundreds of members of the Burmese exile community at a Queens high school. Some of the money raised there went to help HIV/AIDS sufferers in Myanmar.

Thxa Soe isn’t the only activist working for that cause. Shortly after Suu Kyi’s release from house arrest, I met the organizers of the 379 Gayha AIDS shelter at the NLD Party headquarters one weekday afternoon. Security agents with earpieces and cameras were watching from a tea shop across the street as I pulled up to the office building near the Shwedagon Pagoda, a golden stupa that towers 30 stories over central Yangon and is the most venerated Buddhist shrine in Myanmar. The large, ground-floor space was bustling with volunteers in their 20s and 30s, journalists, human-rights activists and other international visitors, and people from Myanmar’s rural countryside who had come seeking food and other donations. Posters taped on the walls depicted Suu Kyi superimposed over a map of Myanmar and images of Che Guevara and her father.

Over a lunch of rice and spicy beef delivered by pushcart, Phyu Phyu Thin, 40, the founder of the HIV/AIDS shelter, told me about its origins. In 2002, concerned by the lack of treatment facilities and retroviral drugs outside Yangon and Mandalay, Suu Kyi recruited 20 NLD neighborhood youth leaders to raise awareness of HIV/AIDS. Estimates suggest that at least a quarter million Burmese are living with HIV.

Even in Yangon, there is only one hospital with an HIV/AIDS treatment facility. Eventually, Phyu Phyu Thin established a center in the capital where rural patients could stay. She raised funds, gathered building materials and constructed a two-story wooden building next door to her house. Today, a large room, crammed wall to wall with pallets, provides shelter to 90 HIV-infected men, women and children from the countryside. Some patients receive a course of retroviral drugs provided by international aid organizations and, if they improve sufficiently, are sent home with medication and monitored by local volunteers. At 379 Gayha, says Phyu Phyu Thin, patients “get love, care and kindness.”

In trying to close the shelter, the government has used a law that requires people staying as houseguests anywhere in Myanmar to obtain permits and report their presence to local authorities. The permits must be renewed every seven days. “Even if my parents come for a visit, I have to inform,” Yar Zar, the 30-year-old deputy director of the shelter, told me. In November, a day after Suu Kyi visited the shelter, officials refused to renew the permits of the 120 patients at the facility, including some close to death, and ordered them to vacate the premises. “The authorities were jealous of Aung San Suu Kyi,” says Phyu Phyu Thin. She and other NLD youth leaders sprang into action—reaching out to foreign journalists, rallying Burmese artists, writers and neighborhood leaders. “Everybody came out to encourage the patients,” Phyu Phyu Thin told me. After a week or so, the authorities backed down. “It was a small victory for us,” she says, smiling.

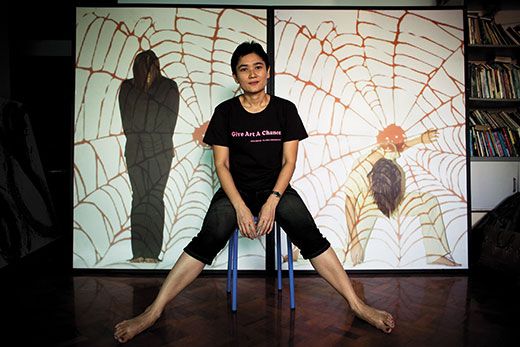

Ma Ei is perhaps the most creative and daring of the avant-garde artists. To visit her in Yangon, I walked up seven dingy flights of stairs to a tiny apartment where I found a waif-like woman of 32 sorting through a dozen large canvases. Ma Ei’s unlikely journey began one day in 2008, she told me, after she was obliged to submit canvases from her first exhibit—five colorful abstract oil paintings—to the censorship board. “It made me angry,” she said in the halting English she picked up watching American movies on pirated DVDs. “This was my own work, my own feelings, so why should I need permission to show them? Then the anger just started to come out in my work.”

Since then, Ma Ei has mounted some 20 exhibitions in Yangon galleries—invariably sneaking messages about repression, environmental despoliation, gender prejudice and poverty into her work. “I am a good liar,” she boasted, laughing. “And the censors are too stupid to understand my art.” Ma Ei set out for me a series of disturbing photographic self-portraits printed on large canvases, including one that portrays her cradling her own decapitated head. Another work, part of an exhibit called “What Is My Next Life?” showed Ma Ei trapped in a giant spider’s web. The censors questioned her about it. “I told them it was about Buddhism, and about the whole world being a prison. They let it go.” Her most recent show, “Women for Sale,” consisted of a dozen large photographs showing her own body tightly swaddled in layers and layers of plastic wrap, a critique, she said, of Myanmar’s male-dominated society. “My message is, ‘I am a woman, and I am treated here like a commodity.’ Women in Burma are stuck at the second level, far below men.”

Ma Ei’s closest encounter with the government involved an artwork that, she says, had no political content whatsoever: abstract swirls of black, red and blue that, at a distance, looked vaguely like the number eight. Censors accused her of alluding to the notorious pro-democracy uprising that erupted on August 8, 1988, and went on for five weeks. “It was unintentional,” she says. “Finally they said that it was OK, but I had to argue with them.” She has come to expect confrontation, she says. “I am one of the only artists in Burma who dares to show my feelings to the people.”

Suu Kyi told me that pressure for freedom of expression is growing by the day. Sitting in her office in downtown Yangon, she expressed delight at the proliferation of Web sites such as Facebook, as well as at the bloggers, mobile phone cameras, satellite TV channels and other engines of information exchange that have multiplied since she was placed back under house arrest in 2003, after a one-year release. “With all this new information, there will be more differences of opinion, and I think more and more people are expressing these differences,” she said. “This is the kind of change that cannot be turned back, cannot be stemmed, and if you try to put up a barrier, people will go around it.”

Joshua Hammer first visited Myanmar in 1980; he now lives in Berlin. Photographer Adam Dean is based in Beijing.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)