How to Row Like a Venetian

The art of Venetian rowing has sustained Venice for centuries. Spend the day learning to row from a local expert

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/8d/528d89b1-dead-4afe-b4e5-da854ea575e5/sqj_1510_venice_likelocal_05-for-web.jpg)

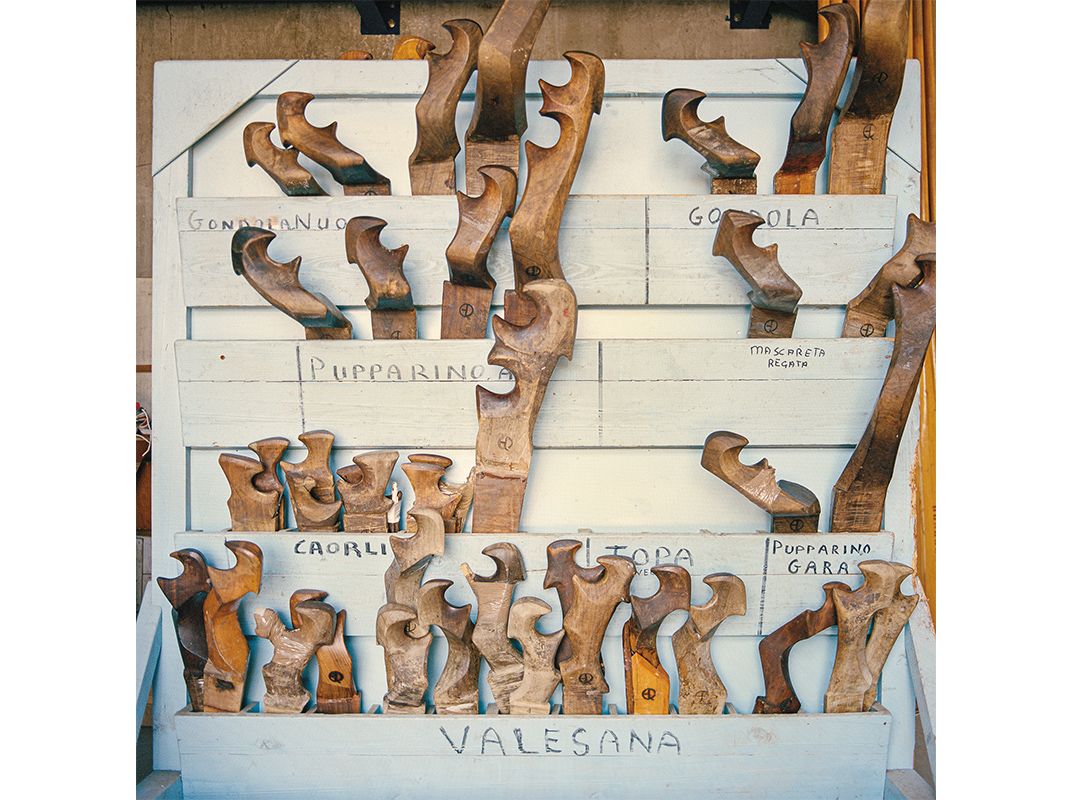

Nothing about the voga alla veneta rowing stroke seems plausible. How can you stand in a skinny, wobbly boat without being tossed over the edge at the slightest ripple? Yet on numerous visits to Venice prior to my move here in 2004, I’d study the poppieri pilots of these keelless, rudderless vessels, watching as they hurled themselves past a buoy in a regatta or slipped under bridges or glided around silent corners before surging finally into the Grand Canal, reclaiming it as their own. With every stroke, they seemed to be issuing a challenge to all comers to achieve a similar kind of grace.

My voga initiation came on a particularly sultry evening in 2005. As a friend and I lingered after dinner at a favorite eatery, the poppiere captain of a 60-year-old batela buranella (one of the few original workboats still galleggiante, or afloat) entered from the back. After a brief chat with his restaurant-owner friends, he turned to invite any willing patrons to go out with him for a midnight vogata on the Grand Canal. I may have been the first on my feet. If I wasn’t already convinced that I wanted to learn more about this elegant form of lagoon navigation, plying the inky black waters of the Canalasso with a massive oar in this workaday craft drew me in completely. Now what?

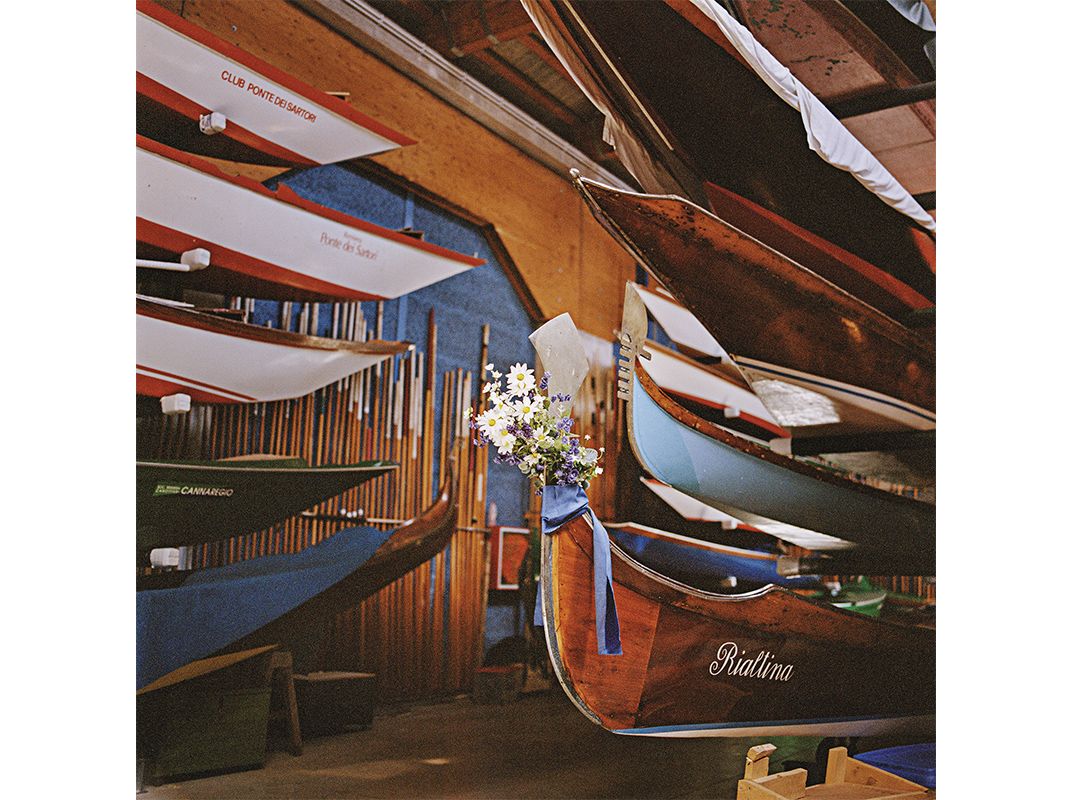

The next step was to find a rowing club that offered lessons. There are more than 25 rowing clubs around the city and throughout the islands of the lagoon, each with a personality as distinctive as any individual Venetian you might meet. Some are smaller, some larger, some more social, some more competitive, some more culturally oriented. The most signorili (stately) of these, the Bucintoro and Querini, were formed before and after 1900 respectively, established for Venetians of the sporting class who wanted to distinguish themselves from the working vogatori, who had been plying the canals for at least a millennium.

The thousand-year reign of the Venetian oar almost came to an end by the late-1900s, however. In postwar Venice, the availability and affordability of outboard motors caused a churning of the once calm lagoon waters, along with a rapid decline of traditional, oar-powered boats and the culture they embodied. Silent (if more laborious) transport and fishing, busy squeri boat-repair yards, fitabatele daily boat rental stations, lagoon excursions, evening outings called freschi to escape summer heat: All began to disappear.

It was the Vogalonga—the 30-plus-kilometer oar-only marathon first held in 1974 to protest the now incessant motorboat wake in the canals—that brought about a “voga renaissance.” At the time, the practice of the voga had declined to such a degree that it was difficult even to find rowers who were competent and strong enough to complete the entire course. With the Vogalonga, however, interest in traditional rowing surged. “The Vogalonga brought about a revolution,” says the Venetian lagoon scholar Giorgio Crovato. “After that, an increasing number of Venetians (and others) began to take up the voga alla veneta ‘for sport.’”

Learning the voga was—and is—a challenge of the mind as well as the body. (As a Venetian friend told me, “We row with our heads; the rest of the world rows with its ass.”) I was already “of a certain age,” and no matter how accomplished I had been at anything else in my life, attempting the voga—much like learning Italian itself—made me feel like a complete idiot. That, and the fact that the Italian I’d managed to learn wasn’t much use on the water: Almost everyone in the Remiera Canottieri Cannaregio rowing club I joined spoke Venetian, which is how I learned the Venetian I now know.

It was almost exclusively thanks to an equally determined group of women of the remiera, however, that I achieved whatever rowing expertise I now have. None of us were kids, and the predominantly male membership assumed that we had no future as capable vogatrici. Our passion for rowing, however, was equaled only by our determination to become competent—if not with help, then on our own. (After all, women had rowed and raced throughout the days of the republic, until Napoleon deemed racing a male-only sport when he took over the city in 1797.) We rowed, we tried, we erred, we experimented, and we improved until each of us became, at least to our own satisfaction, la padrona della barca, the mistress of the boat.

To me, the voga may be the ideal sport. Aside from being utterly Venetian and dating back centuries, it is full body—and no impact. If you can stand, you can vogare. Row by yourself, with one oar or two; together with one or more friends, in one or more of a variety of traditional boats. As you row, you continually lean into a spectacular panorama: reflections of palaces in still canals, the grandeur of the Dolomites on a clear winter’s day, a flock of flamingos amassed in the north lagoon. The position of your body as you propel your craft never lets you forget that you—and Venice itself—are intimately connected to the shallow, 212-square-mile lagoon that extends from Lido di Jesolo in the north to Chioggia in the south. A small, yet expansive, world.

Today, my rowing life takes many forms and brings extraordinary opportunities. In 2008, I was a member of the first all-female crew of the Serenissima—an opulent, traditional 18-rower galley that opens the colorful procession of the Regata Storica. Now I’m the president of the nonprofit association Viva Voga Veneta, which has brought back citywide (and oar-only) freschi with music or other entertainment in the Grand Canal or the lagoon. I have been part of the voga crew for the traditional riverboat festival in Orléans, France, with the Associazione Arzanà and Associazione Settemari, and have explored the Po River delta and the lagoons and canals as far as Cervignano in Friuli on expeditions organized by members of the same clubs. Thanks to the devotion of British vogatori at the City Barge rowing club in Oxford, 14 women of Un Po’ di Donne and the Remiera Giudecca rowed the Thames north and south of Oxford last summer; in June we celebrated the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carta by rowing Venetian style from Windsor to Runnymede—in medieval garb, no less.

Though I had contemplated how to share the voga experience with travelers, it wasn’t until I joined Jane Caporal as co-coordinator of Row Venice that it became not only possible but also a raging success. Our instructors, Venetian by birth or by choice, are almost all female. Together, we have brought back the elegant, extinct batela coda di gambero—a shrimp-tailed craft—to better allow travelers to try their hand at Venetian rowing. Once perhaps the most common vessel on the lagoon—you can spot them in almost any city panorama painted by Guardi, Canaletto, or Carpaccio—they are incredibly stable and spacious, and are ideal for first-time rowers.

The voga alla veneta permeates my life now just as the batela was a vital part of the canals of the city in the time of the Serenissima, the Most Serene Republic of Venice. It’s not surprising to see so many travelers also appreciate the beauty of this very Venetian activity, and try it themselves. Once they have that long oar in hand, they are connected viscerally to Venice as it has always existed, in a state of seemingly timeless grace.

Try your hand at Venetian rowing

Two nonprofit organizations offer lessons in the voga alla veneta specifically for non-Italian-speaking travelers (of course you practice your Italian during the session as well). A lesson could be the ideal complement to historical art and architecture tours; it’s active, environmentally sustainable, and utterly traditional, presenting a unique perspective of the city that only vogatori have.

Row Venice | This group, with almost all female instructors (many of them racing champions), was established by Jane Caporal about five years ago. Row Venice gives 90-minute lessons in historic, “shrimp tailed” battelli code di gambero or other traditional boats (starting at 80 euros for one or two people); a Cichetto Row, which combines a lesson with food and drink at two bàcaro stops (240 euros and up, including refreshments); or a relaxed predinner Grand Canal evening lesson (180 euros for up to four people). Book your preferred date and time online.

Venice Onboard | Three young Venetian entrepreneurs formed this nonprofit to offer a variety of outings, among them a 50-minute sample, a longer series of lessons and even lagoon excursions. They have an assortment of beautifully restored traditional boats and will suggest the appropriate one for your group. Don’t be intimidated by the Italian on the site; write your request in English.

Recommendations:

• Book early in your stay. Lessons are weather dependent (because of storms and strong winds), so leave some flexibility in your itinerary in the rare case you’ll need to reschedule.

• Wear comfortable clothing and flexible shoes (though you’re welcome to remove your shoes in the boat, as some of the instructors will). In summer be sure to bring water and a hat or umbrella for protection from the sun; a waterproof jacket and umbrella will be welcome if the weather makes good on a threat of rain.

• Get accurate directions, and allow plenty of time to find the meeting point. Venice is confusing even for locals, and lessons start in tranquil areas of the city away from the San Marco crush.

• Be patient. The voga is not as “instant” as sit-down rowing. Expertise doesn’t come in the first few strokes. Relax, take your time, allow your body to ease into the movement, and you’ll be plying the canals before you know it.

• You’ll become a member of either organization when you sign up for the lesson of your choice.

Read more from the Venice Issue of the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1510_Venice_Contrib_04.jpg)