On the 1700 block of Wells Street in Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood, a curious red door is hard to miss. It looks like something that belongs in a medieval castle. Every inch of it is ornately carved. The brick façade around the door is studded with tiles laid in an idiosyncratic array of geometric patterns. The modes are different, but they don’t clash.

This mélange of styles typifies the work of Edgar Miller, a 20th-century artist and architect who has been largely overlooked by history. While many people have walked by the door and the façade, very few—likely less than one or two thousand—have ever gotten a chance to see what’s behind it: Glasner Studio, a private apartment completed in 1932 that’s considered Miller’s masterwork. A new virtual tour by the young nonprofit Edgar Miller Legacy, which does not own but has exclusive access to the space, allows anyone to step inside, and learn more about its enigmatic creator.

“Miller’s little-known today because he was ahead of his time,” says Marin Sullivan, an independent curator who was involved in the creation of the virtual tour. “He worked much like contemporary artists do today, crossing disciplines, audiences and pursuits. He was a fine artist as well as an architect and a graphic designer. But, because he didn’t fit into just one category, he got dropped out of history.”

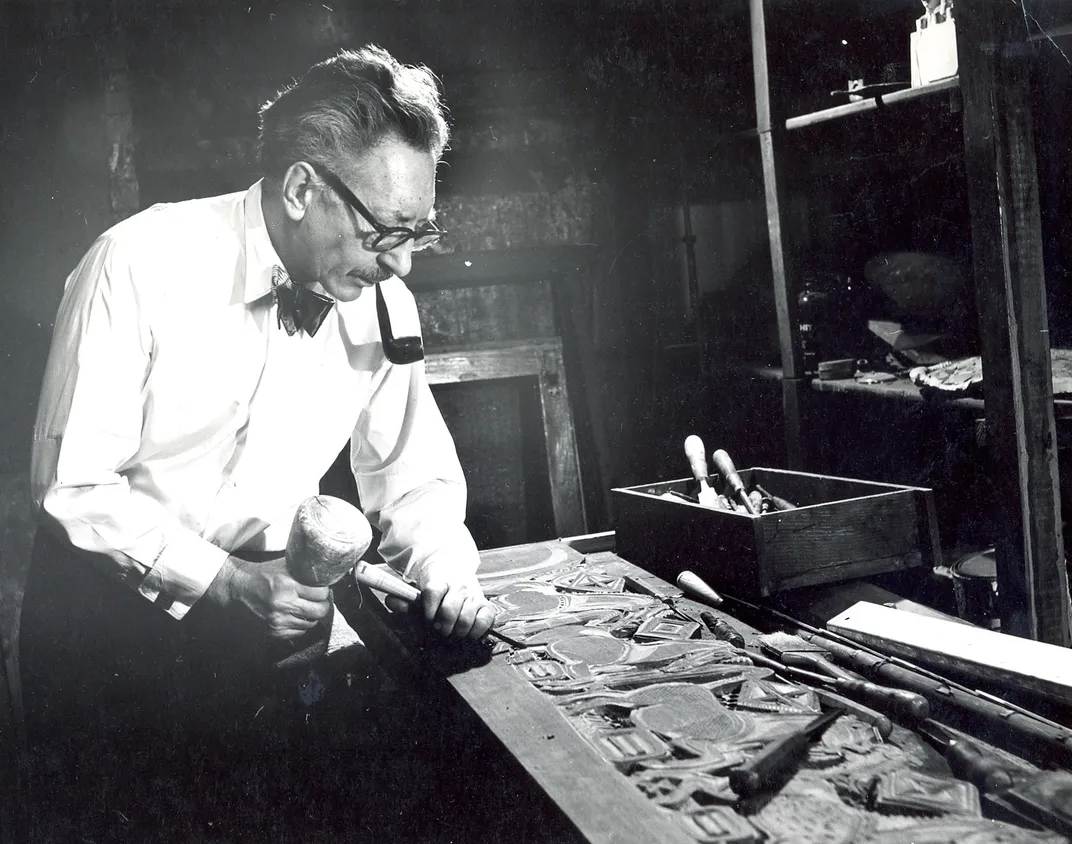

Born in 1899, Miller had a bucolic upbringing, mostly in Idaho, where he developed a fascination with the natural world. From an early age, he had a talent for drawing, which led him to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. But traditional art training bored him. The school was focused on technique, while Miller yearned to engage with big ideas about the meaning of art, according to the 2009 book Edgar Miller and The Handmade Home, the only comprehensive volume on Miller’s work. He dropped out after a couple of years and, in 1919, became an apprentice to Alfonso Iannelli, who was well known as a sculptor, commercial designer and metalworker. Iannelli had created concrete sculptures for the Midway Gardens, a three-acre music pavilion on Chicago’s South Side that was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Miller spent five years at Iannelli’s studio, where he became skilled in sculpture, stone cutting, mural painting, casting and woodcarving. In 1923, an advertisement titled “The Parade of Chicago Artists” described Miller: “the blond boy Michelangelo sculpts, paints, batiks, decorates china, makes drawing, woodcuts, etching, lithographs.”

Through Iannelli, Miller developed relationships with key players in the Chicago art and architecture scene, such as Holabird & Root, one of Chicago’s leading architecture firms. He worked on murals and installations for the firm. He also worked on projects across the country, including ornamentation for North Dakota’s capitol building in Bismarck, an acclaimed series of stained glass windows in architect Barry Byrne’s Church of Christ the King in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and murals for Fred Harvey restaurants—a chain of eateries in railroad depots—in three states. He rarely, if ever, turned down a job, and he worked in both architecture and graphic design. In the ‘30s, Miller’s most prolific decade, his work included stained glass for major office buildings and mausoleums, stone sculptures for churches and other facades, murals for restaurants and private clubs, book covers, and advertisements for the department story Marshall Field and Company. (Some of his architectural projects and murals survive, but many do not). One trade magazine, Modern Advertising on Display, said he “pioneered the use of modern art in advertising,” while Architecture magazine hailed him as “a new luminary.”

While he was working on his commercial projects in the ‘20s, Miller was also making art independently, and he was part of a rich community of bohemian artists. One of them was his friend Sol Kogen, who hatched a plan to create a new artists’ colony in Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood, where rents were low. Kogen had the money to buy old buildings, and his idea was to have artists rehab them in exchange for rent. The first such complex is now known as the Carl Street Studios, at 155 West Burton.

One of Miller’s heroes was William Morris, a leader in the British Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century, which sought to vindicate crafts made by hand and so-called decorative arts in an increasingly industrial world. Morris believed a home could be a complete work of art, bringing together all of the arts. Miller sought to create such a work at Carl Street, and for him that meant that every detail was embellished. “Miller was part of this movement of romantic eclecticism, the idea of art, design and architecture all coming together,” says Zac Bleicher, founder and executive director of Edgar Miller Legacy. The Carl Street Studios were Miller’s first chance to achieve his vision, and he threw himself into it with the feverish intensity with which he approached all his projects. “Miller had to be creating at all times,” Sullivan observes.

Miller made major architectural changes to the Victorian building, including removing floors to create two-story vertical windows. His process remains something of a mystery: An architect, Andrew Ribori, was designated to consult, but Miller rarely sought his advice, instead improvising from rough sketches or nothing at all. He was helped by builders and artisans he knew and trusted, including his brother and sister. While Kogen had enough money to buy the buildings, there wasn’t much budget beyond that, so, Miller salvaged his materials from wrecking sites. From his rural upbringing, Miller was accustomed to working with whatever was at hand, and creative reuse became an important part of his process.

Miller adorned spaces with as many handmade details as he could: frescoes and murals, tile friezes, iron railings, light fixtures he built himself, and built-in fireplaces surrounded by tile mosaics. Bleicher says, “At Carl Street, a little moment of genius will appear around a corner—a stained glass window, or a mosaic.” In the ‘40s, a writer for The New York Times Magazine described the studios: “In this one structure, there’s a touch of Moderne, Deco, Prairie, Tudor, Mission, a little English Country House and Arts and Crafts.”

The Carl Street Studios, which are still intact and privately owned today, were a progenitor of Glasner Studio, which is considered Miller’s masterpiece and is the subject of the new virtual tour. In 1928, Kogen purchased another apartment building at 1734 N. Wells Street, now known as the Kogen-Miller Studios. The wealthy industrialist R.W. Glasner, who had been following Miller’s career, commissioned him to make one of the nine apartments into space where he could entertain. “Finally, Miller had the budget to do everything that he wanted, and Glasner gave him free reign,” Bleicher says. Over several years, Miller packed the four-story, 3,000-square-foot studio with stained glass windows, wood carvings, tilework and bas-reliefs.

The apartment changed hands over the years, but remarkably, Miller’s work remained intact. Frank Furedy, a businessman who held a number of patents, bought the apartment in the 1940s and brought Miller back to create a carved ceiling on the first floor that depicts the world’s greatest scientists and inventors, such as Guglielmo Marconi, who invented the radio. (Furedy himself was included). A carving of a mushroom cloud with “AD 1945” below it reflects the fact that the first atomic bombs had just been dropped. In the ‘60s, the apartment was owned by civil rights activist Lucy Hassell Montgomery, who hosted her radical friends there, including Fred Hampton, a leader in the Black Panther Party hiding out from the FBI, who deemed him a threat. (The apartment was added to the FBI’s hotspot list). In the 2000s, the space was restored by owner Mark Mamolen, and filled with period furniture and collected works by Miller, such as painted ceramics, drawings and pieces of murals.

Edgar Miller Legacy began offering small public tours of Glasner Studio in 2014. The apartment complex is still privately owned—Glasner Studio itself is owned by a member of Bleicher’s family—so access is limited. The organization estimates that fewer than a few thousand people have ever seen the space over the course of its existence. (The fact that his best work is in private homes is yet another reason why Miller remains little-known).

“Glasner Studio is like nothing you’ve ever seen before,” says Richard Cahan, co-author, with Michael Williams, of Edgar Miller and The Handmade Home. “It shows how Miller had an encyclopedic mind, for architecture, humanity and life itself. He did everything in a completely spontaneous manner, and he had fun, unlike most architects. It’s impossible to place him in the pantheon of Chicago architecture, because he was an original.”

The virtual tour allows viewers to explore a 3D rendering of the space and click on various elements to read text, listen to audio clips and watch videos about them. Walking in the door, one can see up to the second level, and a two-story stained glass window. Above the door is a white plaster bas-relief that depicts five muses: dance, music, drama, art and, in the center, architecture. “Miller believed architecture was the highest art form, where science and technology blend with artistic expression and produce harmonious living environments,” Sullivan says in the tour audio.

Visitors can follow the stairs, which are covered by elaborately carved wood latticeworks—some geometric, some featuring flora and fauna—up to the top floor, where they’ll see The Garden of Paradise stained glass window, the space’s apotheosis, both literally and figuratively. Sullivan calls the window, which is nine feet tall and 20 feet wide, spanning an entire wall, “one of the greatest secular stained glass pieces in America.” Jungle animals, birds and nude men and women are stylistically posed in an idyllic garden. In one of the 24 panels, a woman caresses a stag. The window epitomizes Miller’s ideas about the sanctity of nature and his wish for humanity to live in harmony with it. A pitched ceiling makes the room feel like a cathedral.

“All of Miller’s many influences are in that window,” Sullivan says, of The Garden of Paradise. “Medieval, byzantine, modern, organic naturalism, there’s so much synthesized, yet it’s not discordant.” A chevron pattern appears in the window and throughout the house and is thought to demonstrate the influence of Mexican folk traditionalism, in which a zig-zag signifies the cycle of life, ascending from birth into life and then descending into death.

“While nothing can replace seeing Glasner Studio in-person, a virtual tour is in some ways a better way to it, because in person the space can be visually overwhelming,” Cahan says. “I had to walk through it many times before I could grab it in my mind. But I knew immediately I’d never seen anything like it before.”

Edgar Miller Legacy created the virtual tour when Covid-19 made it impossible for people to tour the space in person. Glasner Studio has been closed for public tours since March. The nonprofit hopes the tour will raise awareness of Miller’s work, and encourage preservation of the spaces and more scholarship on the artist. Miller’s papers are housed at the Chicago History Museum, but he has been little studied, Sullivan says. “There’s been a lot of scholarship about art and architecture in mid-century Chicago, but not as much about the interwar years,” she observes.

According to Bleicher, Miller was part of an experimental culture in the 1920s and ‘30s that had a hopeful vision for the future. That vision didn’t pan out because of the Great Depression, and a very sterilized style of architecture and design took over after World War II. “Miller challenged expectations, molds, ideas about what art can be,” he adds. “Exploring the living spaces he created, you see his philosophy of unbridled creativity. We hope people will see that and be inspired.”

For Cahan, Miller’s “legacy” is hard to pin down. “When I think of the word legacy, I think of people following in a person’s footsteps,” he says. “Nobody has followed in Edgar Miller’s footsteps, because nobody can do what he did.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/e4/1ce40b17-287b-49e2-a3ab-94149d0a8a81/glasner_studio_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/70/8a70e01b-424b-4ecc-a3cb-157568d3a87e/glasner_studio_social.jpg)