Everything in This Museum Is Fake

This Vienna art museum pays homage to the art of forgery

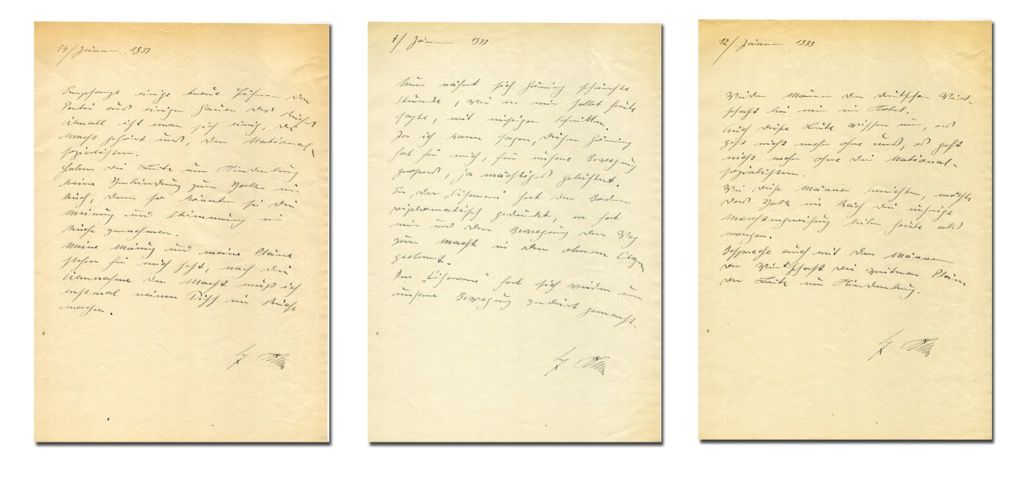

German artist Edgar Mrugalla was incredibly prolific in his lifetime, having painted more than 3,500 pieces by the time he was 65. And yet, not one of those was an original work. Mrugalla was an expert art forger, copying the works of Rembrandt, Picasso, Renoir and many other masters. His self-taught skill even earned him two years in prison, only to be released by working with authorities to uncover which artworks might be forgeries, including his own.

Though none were original, some of Mrugalla’s works are now on display in a museum: the Museum of Art Fakes in Vienna. Diane Grobe, co-owner and founder of the museum that opened in 2005, credits Mrugalla with the inspiration for the opening. “[I was inspired by] his exciting stories,” Grobe told Smithsonian.com via email. “He gave [the museum] our first forgeries — [paintings copying] Rembrandt, Müller [and] Picasso. After this meeting, we [looked] for other counterfeiters with similar exciting lives, [including Thomas] Keating, [Eric] Hebborn [and Han van] Meegeren, and then we began to collect their forgeries.” Now, the museum holds a collection of more than 80 forged works.

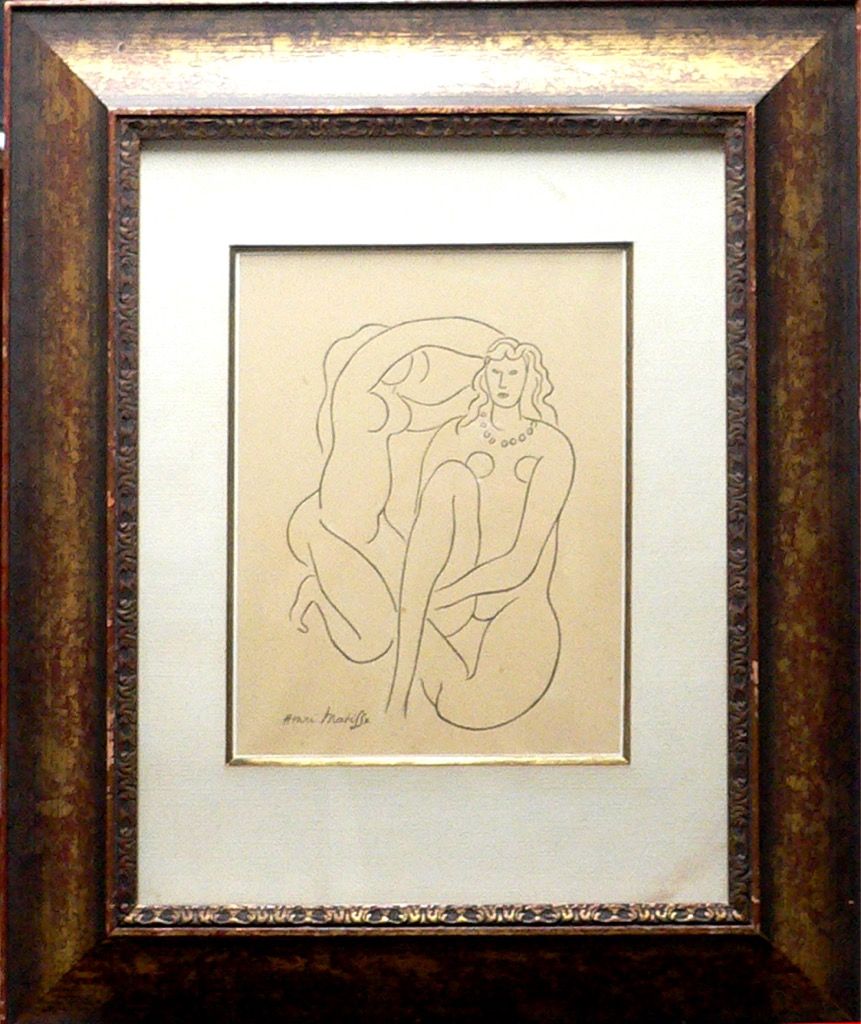

Some of the more unique items in the museum, according to Grobe, include a set of fake diaries written by Konrad Kujau who claimed they had actually been written by Hitler; a forgery in the style of Christian Bernhard Rode sold to an antique shop by a man trying to help out some friends in the German Democratic Republic; and a fake Matisse first identified as a forgery by the artist’s daughter.

One of the other forgers whose work is exhibited in the museum, Han van Meegeren, became famous virtually overnight. After dropping out of architecture school in the early 1900s to focus on his first love, painting, he lived in poverty while painting portraits of citizens in the upper class. But he was unsatisfied; he wanted more acknowledgement for his work. So he moved to southern France in 1932, and there worked to copy paintings by Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer. He became so skilled at his forging work that he eventually painted what, for a time, many considered to be one of Vermeer’s best works: a fake, painted by van Meegeren, called "Emmaus," which he sold to an art museum in Rotterdam for the modern equivalent of $6 million.

But it was another fake that eventually earned van Meegeren his fame. In 1945, he was arrested; he had forged another Vermeer and sold it to second-in-command Nazi Hermann Goering. But, as the war was now over, he was afraid of potential accusations that he had worked with the Nazis, so instead he confessed to faking the painting, and to faking Emmaus and several others. Though found guilty, he died in 1947, just before his year-long sentence was meant to begin.

Each forger featured in the museum learned their trade a different way—whether through schooling, self-teaching, or simply a desire to learn to paint. And virtually all of them were caught, prosecuted, and sometimes sentenced to jail time.

The curators of the museum place great importance on correctly labeling when an artwork is a genuine fake. Three types of works exist inside the museum: copies, meaning it’s a legitimate copy of an existing artwork but does not claim that it’s by the original artist—and for this museum, the original painter should have been deceased for at least 70 years; a standard forgery, which is a piece done in the style of a certain painter and labeled with that artist’s name; or an identical forgery—a copy of an existing piece of artwork labeled with the original artist’s name. All of these are considered to be genuine fakes.

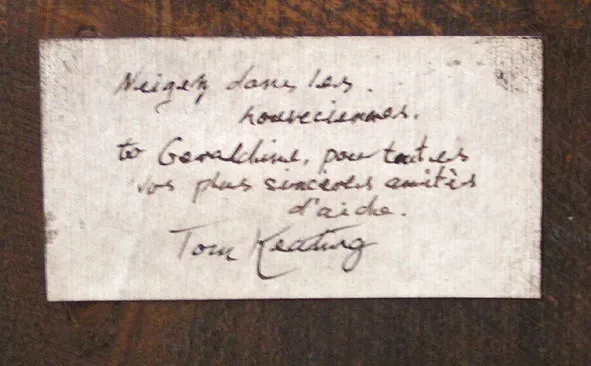

Grobe’s favorite piece in the museum is a faked Jean Puy painting by forger Tom Keating. On the back of the painting, Keating dedicated the work to Geraldine Norman, a famous art expert, who confirmed for the museum that the piece is indeed a forgery. Keating left little hints inside his work, things he called “time bombs” that would ultimately give the painting away as a fake—such as using peculiar materials, adding deliberate flaws or even writing on the canvas with a white lead pencil before painting so it would only be seen if the piece was x-rayed. The museum’s Puy forgery by Keating has one such time bomb included—though to find out what it is, you'll have to visit the museum and look for yourself.

In addition to housing the artworks themselves, the museum also tries to spread awareness of art law as it relates to fakes and forgeries. The production alone of a piece of art mimicking another artist, for example, is not illegal. But once the product is sold under the guise of an original, then it breaks the law. In that sense, the entire Museum of Art Fakes tells something of a crime story, chronicling the world of stolen creativity and intellectual property.

“The museum, with all the crime stories, makes people interested in art,” Grobe said. “It is funny, but also very informative. We allow a different look at art. And because the museum provides information on current art market law, perhaps we will prevent further fraud.”

The collection at the museum continues to grow; the owners are always purchasing new pieces.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)