One Man’s Korean War

John Rich’s color photographs, seen for the first time after more than half a century, offer a vivid glimpse of the “forgotten” conflict

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/koreanwar_nov08_631.jpg)

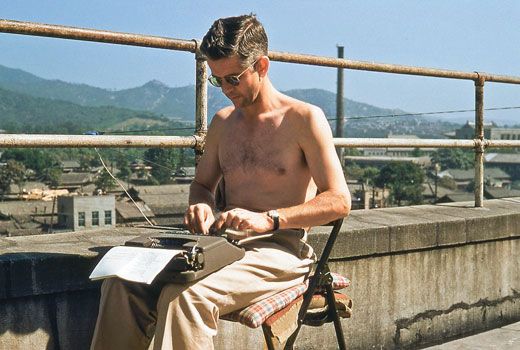

On the June morning in 1950 when war broke out in Korea, John Rich was ensconced in what he calls a "correspondents villa" in coastal Japan, anticipating a long soak in a wooden tub with steam curling off the surface and a fire underneath. Rich's editor at the International News Service had other plans. "Get your fanny back to Tokyo!" he bellowed over the phone. Days later, the 32-year-old reporter was on a landing ship loaded with artillery and bound for Pusan, Korea.

Along with notebooks and summer clothes, Rich carried some Kodachrome film and his new camera, a keepsake from a recent field trip to a Japanese lens factory led by the Life magazine photographer David Douglas Duncan. Rich, who was fluent in Japanese after a World War II stint as an interpreter with the Marines, had tagged along to translate. "It was a little company called Nikon," he recalls.

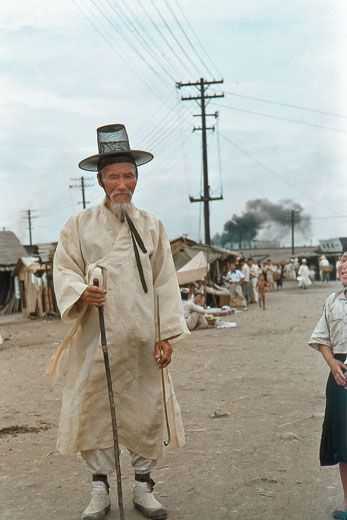

Over the next three years, between filing stories for the wire service and, later, radio and television dispatches for NBC News, Rich snapped close to 1,000 color photographs of wartime Korea. The pictures were meant to be souvenirs, nothing more. "I'd walk around and bang, bang, bang," says Rich, now 91, with hair like dandelion fluff. "If something looked good, I'd shoot away." He photographed from helicopters, on foot and from the rickety jeep he says he bartered for "four bottles of rotgut whiskey." He photographed prisoners of war on Geoje Island and British gunners preparing to fire on occupied Seoul. And he searched out scenes from ordinary life, capturing Korean children at play and women pounding laundry in a river. With color only a click away, Rich was drawn to radiant subjects: in his photographs, little girls wear yellow and fuchsia; purple eggplants gleam in the marketplace; guns spew orange flame.

He had no idea then that the pictures would constitute perhaps the most extensive collection of color photographs of the Korean War. Though Kodachrome had been around since the mid-1930s, World War II had slowed its spread, and photographers continued to favor black-and-white for its greater technical flexibility, not to mention marketability—the major periodicals had yet to publish in color. Duncan, Carl Mydans and other famous photojournalists working in Korea still used black-and-white film almost exclusively.

Rich bought film whenever he was on leave in Japan, and he sent pictures out for processing, but he barely glanced at the developed transparencies, which he tucked away for safekeeping. Rich's Nikon was stolen after the war, and he largely gave up taking photographs.

Then, about a decade ago, Rich, long retired to his birthplace of Cape Elizabeth, Maine, mentioned to a neighbor that he had color slides from the combat years in his attic in a Japanese tea chest. The neighbor, a photographer and Korean War buff, almost toppled over. Rich understood why when he started reviewing the pictures. The "Forgotten War" came back to him in a rush of emerald rice paddies and cyclones of gray smoke. "Those white hills, that blue, blue sea," he says. "I lay awake at night, reliving the war."

A few of the pictures surfaced in Rich's local newspaper, the Portland Press Herald, and in a South Korean paper after Rich visited the country in the late 1990s. And they were featured this past summer in "The Korean War in Living Color: Photographs and Recollections of a Reporter," an exhibition at the Korean Embassy in Washington, D.C. These pages mark their debut in a national publication.

The photographs have claimed a unique place in war photography, from the blurry daguerreotypes of the Mexican-American War to Vietnam, when color images became more commonplace, to the digital works now coming out of the Middle East. Once a history confined to black-and-white suddenly materializes in color, it's always a bit startling, says Fred Ritchin, a New York University photography professor who studies conflict images: "When you see it in color you do a double take. Color makes it contemporary."

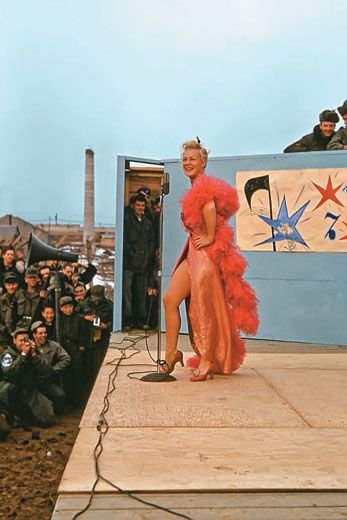

Rich, who covered the Korean War in its entirety, remembers two colors the most: the Windex blue of the ocean and sky, and the brown of sandbags, dusty roads and fields of ginseng. In his photographs, though, red seems the most vivid. It's the shade of Betty Hutton's pumps as she danced for the troops, and the diamonds on the argyle socks of the Scottish regiment that marched to bagpipes squealing "Highland Laddie" (a memory Rich invariably relates with liberal rolling of r's). Photographers, in fact, long revered Kodachrome for its vibrant crimsons and garnets. And yet, during Vietnam, these reds also led some critics to argue that war should not be photographed in color. "We hadn't seen the injured in red before," says Anne Tucker, curator of photography at Houston's Museum of Fine Arts, which is planning an exhibition of war images. To be sure, Rich's collection does not dwell on death, though it includes a picture taken south of Seoul in the spring of 1951 of two fallen Chinese soldiers and a scarlet splash on the ground.

Wearing pressed charcoal pants and house slippers, Rich shuffles industriously around his seaside cottage, where even the windowsills are stacked with figurines and carvings collected during a reporter's well-traveled life. Working mostly for NBC News, he covered Vietnam and many of the major conflicts of the 20th century—including, remarkably, the first Gulf War, when he was in his 70s and armed with shaky credentials from a weekly newspaper in Maine. (He says he briefly contemplated shipping out to the latest Iraq conflict.) The son of a postman and a homemaker, he played tennis with future Japanese Emperor Akihito, traveled to China with Richard Nixon and lived beside barbed wire in a partitioned Berlin. Three of his four children live in Asia (the other is a U.S. magistrate in Portland), and his wife, Doris Lee (whom he met in Korea and calls his "Seoul mate"), is never far from his side.

He has returned to his photographs because his eyesight is going. Glaucoma makes even reading the newspaper difficult and, especially when he wears the dark sunglasses he's prescribed, dims the goldenrod bouncing outside his door.

Riffling through piles of prints, Rich pulls out one of a South Korean soldier with pink flowers lashed to his helmet. "This is when spring came to Korea," he explains. The bright blossoms don't look like camouflage: the young man must have wanted to be seen. And now, finally, he is.

Abigail Tucker, the magazine's staff writer, last reported on the salmon crisis.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.