One Way to Visit Bhutan Is By Way of El Paso

After making its debut at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, a temple from the Himalayan kingdom is uniquely reincarnated on a Texan university campus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c3/a2/c3a2fdba-20fb-4009-b0eb-b08f4c64b3c6/1lhakhangduskweb.jpg)

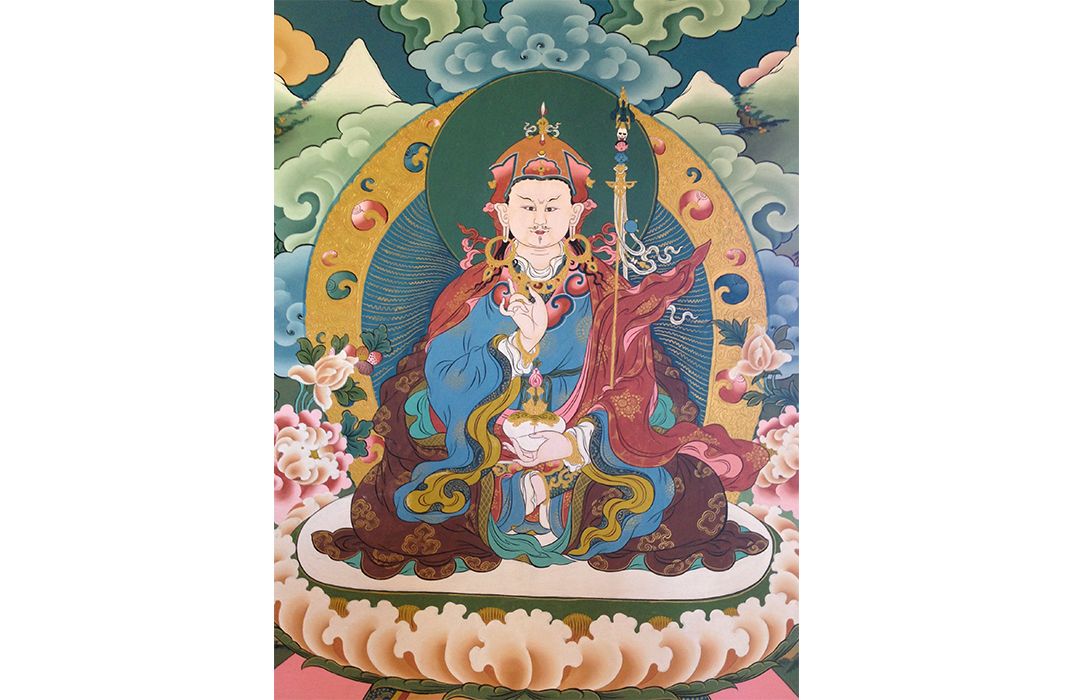

Ursula Landry and Jean McDaniel, longtime friends and yoga buddies, are in awe as they tour a Bhutanese temple on the campus of the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). The intricately carved woodwork and the colorful, floor-to-ceiling paintings of Buddhist deities look like nothing else here in this town on the border of Mexico.

“It’s mind-boggling to think someone painted all of this, did all of this,” said McDaniel, a native of El Paso who coyly says she graduated from the university many years ago. “It makes you want to go to Bhutan.”

But why would she? Instead, she can get a healthy dose of the Himalayan Kingdom, without the jetlag or the expense, minutes from her home. The college campus is now, more than ever, poised to serve as the perfect primer for anyone curious about the distant Asian land that some call “the last Shangri-la," which only opened its borders to tourism in the 1970s. The tiny nation, sandwiched between Tibet and India, didn’t allow the transmission of television or Internet until 1999, and just getting there can cost thousands of dollars. Tourists are required to pay a daily visa fee of around $250, which includes a driver and guide. A perilously narrow main road snakes and winds across the entire country—one reason independent travel is not permitted. For the most intrepid traveler, though, this sparsely populated landscape can be the trip of a lifetime, with unspoiled vistas and magnificent flora and fauna.

When asked and like most locals, McDaniel and her friend Landry aren’t exactly sure just why the university features Bhutanese-style architecture on each of its buildings, from the guard shacks to the library to the parking garage. They only know that it has been this way forever—almost since the school was first established 100 years ago. Nor are they quite sure how this authentic 40-by-40 foot temple, called a lhakhang, came to find a home right next to a beautiful new 16-acre park in the center of the school. It’s the only structure of its kind ever to be built by native artisans outside Bhutan; and its journey to El Paso began with a stop seven years ago on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

The temple was originally constructed as a temporary showpiece for the 2008 Smithsonian Folklife Festival. Its interior was crafted by skilled craftsmen in Bhutan, then shipped to the United States for assembly on the Mall by a Bhutanese and American crew. (At the end of the long workday, the Americans taught their colleagues—most of whom had never even seen a plane before, much less been on one—softball.) That summer, a million people visited the festival, and over the course of two weeks, hundreds of thousands waited in line for a chance to step foot inside the temple.

But according to Preston Scott, curator of the festival's Bhutan exhibition, "after the show, nothing is saved." So the distinctive red-roofed structure was headed straight for the dumpster until Diana Natalicio, the long-standing UTEP president, claimed it for the campus. She’s had it tucked away most of these past seven years in a giant storage facility while a massive renovation project took place on the quad.

“It would have been a shame to cut this thing up and throw it away,” says Scott, who is pleased with the structure's new permanent home. “Most of the themes (depicted on the walls of the temple) are about wisdom and compassion, and that’s the heart and soul of any university or any learning community in the world, the highest values you can teach,” he adds. “That’s what this is all about at a very deep and subtle level.”

In retrofitting it for its permanent home, stone was used for the exterior walls this time around, as opposed to the plywood that propped it up in 2008. A wheelchair ramp and HVAC system are about the only two American features—elements you won’t find, at least yet, in similar structures in Bhutan.

Yet why would a university located literally across the street from Juarez, Mexico, be replete with Bhutanese architecture, with every single structure on the campus mimicking its style? For nearly a hundred years, the school has had a unique, if capricious, tie to Bhutan. It began in 1914 when Kathleen Worrell, the wife of the school’s first dean provost, read an article in National Geographic magazine. Entitled "Castles in the Air," it was the first published report about the remote nation. The article and photographs by a British Raj administrator named John Claude White enchanted her.

In 1916 1917, when a fire destroyed the buildings that comprised the original campus, Worrell asked her husband to rebuild using the architectural style depicted in the story. The Franklin Mountains in El Paso, she argued, resembled the Himalayas that she saw in the photographs.

Despite this unusual provenance, few in the university community are aware of the story of how their school came to look the way it does, with sloping roofs and walls, inset windows, colorful mosaic mandalas and spires. McDaniel said she had no idea about the school’s history when she attended. Most current students seemed to have an inaccurate interpretation of the facts: “I think the Kingdom donated money,” said one young man languishing at the new campus park adjacent to the temple. “Someone’s wife or daughter went there, right?” said another. And even fewer knew much about Bhutan, which today is fabled for its unique development strategy, a commitment to measured growth versus unbridled capitalism, called “Gross National Happiness.”

It wasn’t till a campus administrator wrote to the then-Queen of Bhutan in the 1960s—a decade before the country began modernizing and slowly opening its borders to tourists—that a formal relationship between the school and the country was established. Today, the campus serves as a living museum to Bhutan.

Dotted across the campus are other relics collected over the years from the Kingdom, including three 16- to 20-foot tall tapestry scrolls known as thangkhas, and an ornate 23-foot-long altar that resides in the lobby of the library. The school also owns a rare copy of the five-foot 7-inch tall and 133 pound photographic folio, entitled Bhutan: A Visual Odyssey Across the Last Himalayan Kingdom, recognized by Guinness as the world’s largest published book.

Natalicio says the addition of the structure honors the long-standing connection El Paso has with Bhutan. Increasing the number of Bhutanese students on campus has done that, too. Eighteen students are currently enrolled, more than at any other institution in the United States.

The Bhutanese students find they serve each day on campus as living emissaries for their homeland. At the temple’s opening, two of them patiently explained to curious visitors how at home, shoes would have to be removed before entering a lhakhang. “When I was in New York, people used to say, ‘Bhutan, where is that?’” said Rigden Chungdu, a freshman finance major from Thimphu, the capital city. Now that he lives in El Paso, he said,“I say I’m from Bhutan and they say, ‘Oh, Bhutan, yes, UTEP.’ And I feel really happy about it.”

Radio Shangri-La: What I Discovered on my Accidental Journey to the Happiest Kingdom on Earth

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Lisa-Napoli.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/2e/d92e0ee6-de3f-40db-b9b7-37fa40407120/jh002767web.jpg)