Out of Time

The volatile Korubo of the Amazon still live in almost total isolation. Indian tracker Sydney Possuelo is trying to keep their world intact

Deep in the amazon jungle, i stumble along a sodden track carved through steamy undergrowth, frequently sinking to my knees in the mud. Leading the way is a bushybearded, fiery-eyed Brazilian, Sydney Possuelo, South America’s leading expert on remote Indian tribes and the last of the continent’s great explorers. Our destination: the village of a fierce tribe not far removed from the Stone Age.

We’re in the Javari Valley, one of the Amazon’s “exclusion zones”—huge tracts of virgin jungle set aside over the past decade by the government of Brazil for indigenous Indians and off limits to outsiders. Hundreds of people from a handful of tribes live in the valley amid misty swamps, twisting rivers and sweltering rain forests bristling with anacondas, caimans and jaguars. They have little or no knowledge of the outside world, and often face off against each other in violent warfare.

About half a mile in from the riverbank where we docked our boat, Possuelo cups his hands and shouts a melodious “Eh-heh.” “We’re near the village,” he explains, “and only enemies come in silence.” Through the trees, a faint “Eh-heh” returns his call.

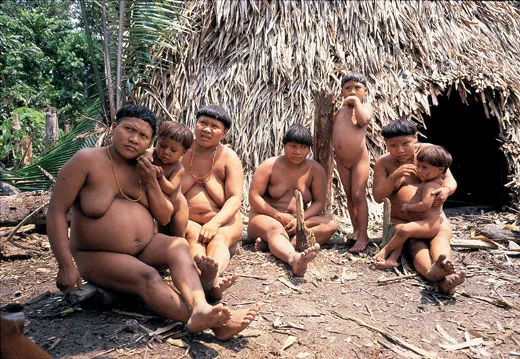

We keep walking, and soon the sunlight stabbing through the trees signals a clearing. At the top of a slope stand about 20 naked Indians—the women with their bodies painted blood red, the men gripping formidable-looking clubs. “There they are,” Possuelo murmurs, using the name they’re called by other local Indians: “Korubo!” The group call themselves “Dslala,” but it’s their Portuguese name I’m thinking of now: caceteiros, or “head-bashers.” I remember his warning of a half-hour earlier as we trudged through the muck: “Be on your guard at all times when we’re with them, because they’re unpredictable and very violent. They brutally murdered three white men just two years ago.”

My journey several thousand years back in time began at the frontier town of Tabatinga, about 2,200 miles northwest of Rio de Janeiro, where a tangle of islands and sloping mud banks shaped by the mighty Amazon forms the borders of Brazil, Peru and Colombia. There, Possuelo and I boarded his speedboat, and he gunned it up the JavariRiver, an Amazon tributary. “Bandits lurk along the river, and they’ll shoot to kill if they think we’re worth robbing,” he said. “If you hear gunfire, duck.”

A youthful, energetic 64, Possuelo is head of the Department for Isolated Indians in FUNAI, Brazil’s National Indian Bureau. He lives in the capital city, Brasília, but he’s happiest when he’s at his base camp just inside the JavariValley exclusion zone, from which he fans out to visit his beloved Indians. It’s the culmination of a dream that began as a teenager, when like many kids his age, he fantasized about living a life of adventure.

The dream began to come true 42 years ago, when Possuelo became a sertanista, or “backlands expert”—drawn, he says, “by my wish to lead expeditions to remote Indians.” A dying breed today, the sertanistas are peculiar to Brazil, Indian trackers charged by the government with finding tribes in hard to reach interior lands. Most sertanistas count themselves lucky to have made “first contact”—a successful initial nonviolent encounter between a tribe and the outside world—with one or two Indian tribes, but Possuelo has made first contact with no fewer than seven. He’s also identified 22 sites where uncontacted Indians live, apparently still unaware of the larger world around them except for the rare skirmish with a Brazilian logger or fisherman who sneaks into their sanctuary. At least four of these uncontacted tribes are in the JavariValley. “I’ve spent months at a time in the jungle on expeditions to make first contact with a tribe, and I’ve been attacked many, many times,” he says. “Colleagues have fallen at my feet, pierced by Indian arrows.” Since the 1970s, in fact, 120 FUNAI workers have been killed in the Amazon jungles.

Now we’re on the way to visit a Korubo clan he first made contact with in 1996. For Possuelo it’s one of his regular check-in visits, to see how they’re faring; for me it’s a chance to be one of the few journalists ever to spend several days with this group of people who know nothing about bricks, or electricity, or roads or violins or penicillin or Cervantes or tap water or China or almost anything else you can think of.

Our boat passes a river town named Benjamin Constant, dominated by a cathedral and timber mill. Possuelo glares at both. “The church and loggers are my biggest enemies,” he tells me. “The church wants to convert the Indians to Christianity, destroying their traditional ways of life, and the loggers want to cut down their trees, ruining their forests. It’s my destiny to protect them.”

At the time the portuguese explorer Pedro Cabral strode ashore in A.D. 1500 to claim Brazil’s coast and vast inland for his king, perhaps as many as ten million Indians lived in the rain forests and deltas of the world’s secondlongest river. During the following centuries, sertanistas led white settlers into the wilderness to seize Indian lands and enslave and kill countless tribespeople. Hundreds of tribes were wiped out as rubber tappers, gold miners, loggers, cattle ranchers and fishermen swarmed over the pristine jungles. And millions of Indians died from strange new diseases, like the flu and measles, for which they had no immunity.

When he first became a sertanista, Possuelo himself was seduced by the thrill of the dangerous chase, leading hundreds of search parties into Indian terri-tory—no longer to kill the Natives, but to bring them out of their traditional ways and into Western civilization (while opening up their lands, of course, to outside ownership). By the early 1980s, though, he had concluded that the clash of cultures was destroying the tribes. Like Australia’s Aborigines and Alaska’s Inuit, the Indians of the AmazonBasin were drawn to the fringes of the towns that sprang up in their territory, where they fell prey to alcoholism, disease, prostitution and the destruction of their cultural identity. Now, only an estimated 350,000 Amazon Indians remain, more than half in or near towns. “They’ve largely lost their tribal ways,” Possuelo says. The cultural survival of isolated tribes like the Korubo, he adds, depends on “our protecting them from the outside world.”

In 1986, Possuelo created the Department for Isolated Indians and—in an about-face from his previous work—championed, against fierce opposition, a policy of discouraging contact with remote Indians. Eleven years later he defied powerful politicians and forced all non-Indians to leave the JavariValley, effectively quarantining the tribes that remained. “I expelled the loggers and fishermen who were killing the Indians,” he boasts.

Most of the outsiders were from Atalaia—at 50 miles downriver, the nearest town to the exclusion zone. As we pass the town, where a marketplace and huts spill down the riverbank, Possuelo tells a story. “Three years ago, more than 300 men armed with guns and Molotov cocktails”—angry at being denied access to the valley’s plentiful timber and bountiful fishing —“came up to the valley from Atalaia planning to attack my base,” he says. He radioed the federal police, who quickly arrived in helicopters, and after an uneasy standoff, the raiders turned back. And now? “They’d still like to destroy the base, and they’ve threatened to kill me.”

For decades, violent clashes have punctuated the longrunning frontier war between the isolated Indian tribes and “whites”—the name that Brazilian Indians and non-Indians alike use to describe non-Indians, even though in multiracial Brazil many of them are black or of mixed race—seeking to profit from the rain forests. More than 40 whites have been massacred in the JavariValley, and whites have shot dead hundreds of Indians over the past century.

But Possuelo has been a target of settler wrath only since the late 1990s, when he led a successful campaign to double the size of the exclusion zones; the restricted territories now take up 11 percent of Brazil’s huge landmass. That’s drawn the attention of businessmen who wouldn’t normally care much about whether a bunch of Indians ever leaves the forest, because in an effort to shield the Indians from life in the modern age, Possuelo has also safeguarded a massive slab of the earth’s species-rich rain forests. “We’ve ensured that millions of hectares of virgin jungle are shielded from the developers,” he says, smiling. And not everyone is as happy about that as he is.

About four hours into our journey from Tabatinga, Possuelo turns the speedboat into the mouth of the coffeehued ItacuaiRiver and follows that to the ItuiRiver. We reach the entrance to the JavariValley’s Indian zone soon afterward. Large signs on the riverbank announce that outsiders are prohibited from venturing farther.

A Brazilian flag flies over Possuelo’s base, a wooden bungalow perched on poles overlooking the river and a pontoon containing a medical post. We’re greeted by a nurse, Maria da Graca Nobre, nicknamed Magna, and two fearsome-looking, tattooed Matis Indians, Jumi and Jemi, who work as trackers and guards for Possuelo’s expeditions. Because the Matis speak a language similar to the lilting, high-pitched Korubo tongue, Jumi and Jemi will also act as our interpreters.

In his spartan bedroom, Possuelo swiftly exchanges his bureaucrat’s uniform—crisp slacks, shoes and a black shirt bearing a FUNAI logo—for his jungle gear: bare feet, ragged shorts and a torn, unbuttoned khaki shirt. In a final flourish, he flings on a necklace hung with a bullet-size cylinder of antimalarial medicine, a reminder that he’s had 39 bouts with the disease.

The next day, we head up the Itui in an outboard-rigged canoe for the land of the Korubo. Caimans doze on the banks while rainbow-hued parrots fly overhead. After half an hour, a pair of dugouts on the riverbank tell us the Korubo are near, and we disembark to begin our trek along the muddy jungle track.

When at last we come face to face with the Korubo in the sun-dappled clearing, about the size of two football fields and scattered with fallen trees, Jumi and Jemi grasp their rifles, warily watching the men with their war clubs. The Korubo stand outside a maloca, a communal straw hut built on a tall framework of poles and about 20 feet wide, 15 feet high and 30 feet long.

The semi-nomadic clan moves between four or five widely dispersed huts as their maize and manioc crops come into season, and it had taken Possuelo four lengthy expeditions over several months to catch up to them the first time. “I wanted to leave them alone,” he says, “but loggers and fishermen had located them and were trying to wipe them out. So I stepped in to protect them.”

They weren’t particularly grateful. Ten months later, after intermittent contact with Possuelo and other FUNAI fieldworkers, the clan’s most powerful warrior, Ta’van, killed an experienced FUNAI sertanista, Possuelo’s close friend Raimundo Batista Magalhaes, crushing his skull with a war club. The clan fled into the jungle, returning to the maloca only after several months.

Now Possuelo points out Ta’van—taller than the others, with a wolfish face and glowering eyes. Ta’van never relaxes his grip on his sturdy war club, which is longer than he is and stained red. When I lock eyes with him, he glares back defiantly. Turning to Possuelo, I ask how it feels to come face to face with his friend’s killer. He shrugs. “We whites have been killing them for decades,” he says. Of course, it’s not the first time that Possuelo has seen Ta’van since Magalhaes’ death. But only recently has Ta’van offered a reason for the killing, saying simply, “We didn’t know you then.”

While the men wield the clubs, Possuelo says that “the women are often stronger,” so it doesn’t surprise me to see that the person who seems to direct the Korubo goings-on is a woman in her mid-40s, named Maya. She has a matronly face and speaks in a girlish voice, but hard dark eyes suggest an unyielding nature. “Maya,” Possuelo tells me, smiling, “makes all the decisions.” By her side is Washman, her eldest daughter, grim-faced and in her early 20s. Washman has “the same bossy manner as Maya,” Possuelo adds with another smile.

Their bossiness may extend to ordering murders. Two years ago three warriors led by Ta’van and armed with their clubs—other Indian tribes in the JavariValley use bows and arrows in war, but the Korubo use clubs—paddled their dugout down the river until they came upon three white men just beyond the exclusion zone, cutting down trees. The warriors smashed the whites’ heads to pulp and gutted them. Possuelo, who was in Atalaia when the attack occurred, rushed upriver to where the mutilated bodies lay, finding the murdered men’s canoe “full of blood and pieces of skull.”

Grisly as the scene was, Possuelo was not displeased when news of the killing spread quickly in Atalaia and other riverside settlements. “I prefer them to be violent,” he says, “because it frightens off intruders.” Ta’van and the others have not been charged, a decision Possuelo supports: the isolated Indians from the JavariValley, he says, “have no knowledge of our law and so can’t be prosecuted for any crime.”

After possuelo speaks quietly with Maya and the others for half an hour in the clearing, she invites him into the maloca. Jemi, Magna and most of the clan follow, leaving me outside with Jumi and a pair of children, naked like their parents, who exchange shy smiles with me. Ayoung spider monkey, a family pet, clings to one little girl’s neck. Maya’s youngest child, Manis, sits beside me, cradling a baby sloth, also a pet.

Even with Jumi nearby, I glance about warily, not trusting the head bashers. About an hour later, Possuelo emerges from the maloca. At Tabatinga I’d told him I could do a haka, a fierce Maori war dance like the one made famous by the New Zealand national rugby team, which performs it before each international match to intimidate its opponents. “If you do a haka for the Korubo, it’ll help them accept you,” he says to me now.

Led by Maya, the Korubo line up outside the maloca with puzzled expressions as I explain that I’m about to challenge one of their warriors to a fight—but, I stress, just in fun. After Possuelo tells them this is a far-off tribe’s ritual before battle, Shishu, Maya’s husband, steps forward to accept the challenge. I gulp nervously and then punch my chest and stamp my feet while screaming a bellicose chant in Maori. Jumi translates the words. “I die, I die, I live, I live.” I stomp to within a few inches of Shishu, poke out my tongue Maoristyle, and twist my features into a grotesque mask. He stares hard at me and stands his ground, refusing to be bullied. As I shout louder and punch my chest and thighs harder, my emotions are in a tangle. I want to impress the warriors with my ferocity but can’t help fearing that if I stir them up, they’ll attack me with their clubs.

I end my haka by jumping in the air and shouting, “Hee!” To my relief, the Korubo smile widely, apparently too practiced in real warfare to feel threatened by an unarmed outsider shouting and pounding his flabby chest. Possuelo puts an arm around my shoulder. “We’d better leave now,” he says. “It’s best not to stay too long on the first visit.”

The next morning we return to the maloca, where Ta’- van and other warriors have painted their bodies scarlet and flaunt head and armbands made from raffia streamers. Possuelo is astonished, never having seen them in such finery before. “They’ve done it to honor your haka,” he says with a grin.

Shishu summons me inside the maloca. Jumi, rifle at the ready, follows. The low narrow entrance—a precaution against a surprise attack—forces me to double over. As my eyes adjust to the dim light, I see the Korubo sprawled in vine hammocks strung low between poles holding up the roof or squatting by small fires. Stacked overhead on poles running the length of the hut are long slender blowpipes; axes and woven-leaf baskets lean against the walls. Holes dug into the dirt floor hold war clubs upright, at the ready. There are six small fireplaces, one for each family. Magna bustles about the hut, performing rudimentary medical checks and taking blood samples to test for malaria.

Maya, the hut’s dominant presence, sits by a fireplace husking corn, which she’ll soon begin grinding into mash. She hands me a grilled cob; delicious. Even the warriors are cooking and cleaning: muscular Teun sweeps the hut’s earthen floor with a switch of tree leaves while Washman supervises. Tatchipan, a 17-year-old warrior who took part in the massacre of the white men, squats over a pot cooking the skinned carcass of a monkey. Ta’van helps his wife, Monan, boil a string of fish he’d caught in the river.

“The Korubo eat very well, with very little fat or sugar,” says Magna. “Fish, wild pig, monkeys, birds and plenty of fruit, manioc and maize. They work hard and have a healthier diet than most Brazilians, so they have long lives and very good skin.” Apart from battle wounds, the most serious illness they suffer is malaria, brought to the Amazon by outsiders long ago.

The men squat in a circle and wolf down the fish, monkey and corn. Ta’van breaks off one of the monkey’s arms complete with tiny hand and gives it to Tatchipan, who gnaws the skimpy meat from the bone. Even as they eat, I remain tense, worried they could erupt into violence at any moment. When I mention my concerns to Magna, whose monthly medical visits have given her a peek into the clan members’ lives unprecedented for an outsider, she draws attention to their gentleness, saying, “I’ve never seen them quarrel or hit their children.”

But they do practice one chilling custom: like other Amazon Indians, they sometimes kill their babies. “We’ve never seen it happen, but they’ve told us they do it,” Magna says. “I know of one case where they killed the baby two weeks after birth. We don’t know why.”

Once past infancy, children face other dangers. Several years ago, Maya and her 5-year-old daughter, Nwaribo, were bathing in the river when a massive anaconda seized the child, dragging her underwater. She was never seen again. The clan built a hut at the spot, and several of them cried day and night for seven days.

After the warriors finish eating, Shishu suddenly grips my arm, causing my heart to thump in terror. “You are nowa, a white man,” he says. “Some nowa are good, but most are bad.” I glance anxiously at Ta’van, who stares at me without expression while cradling his war club. I pray that he considers me one of the good guys.

Shishu grabs a handful of red urucu berries and crushes them between his palms, then spits into them and slathers the bloody-looking liquid on my face and arms. Hunching over a wooden slab studded with monkey teeth, he grinds a dry root into powder, mixes it with water, squeezes the juice into a coconut shell and invites me to drink. Could it be poison? I decide not to risk angering him by refusing it, and smile my thanks. The muddy liquid turns out to have an herbal taste, and I share several cups with Shishu. Once I’m sure it won’t kill me, I half expect it to be a narcotic like kava, the South Seas concoction that also looks like grubby water. But it has no noticeable effect.

Other Korubo potions are not as benign. Later in the day Tatchipan places on a small fire by the hut’s entrance a bowl brimming with curare, a black syrup that he makes by pulping and boiling a woody vine. After stirring the bubbling liquid, he dips the tips of dozens of slender blowpipe darts into it. The curare, Shishu tells me, is used to hunt small prey like monkeys and birds; it’s not used on humans. He points to his war club, nestled against his thigh, and then his head. I get the message.

As the sun goes down, we return to Possuelo’s base; even Possuelo, who the clan trusts more than any other white man, considers it too dangerous to stay overnight in the maloca. Early the next morning we’re back, and they ask for the Maori war dance again. I comply, this time flashing my bare bottom at the end as custom demands. It may be the first time they’ve ever seen a white man’s bum, and they roar with laughter at the sight. Still chuckling, the women head for the nearby maize and manioc fields. Shishu, meanwhile, hoists a 12-foot-long blowpipe on his shoulder and strings a bamboo quiver, containing dozens of curare darts, around his neck. We leave the clearing together, and I struggle to keep up with him as he lopes through the shadowy jungle, alert for prey.

Hour slips into hour. Suddenly, he stops and shades his eyes while peering up into the canopy. I don’t see anything except tangled leaves and branches, but Shishu has spotted a monkey. He takes a dab of a gooey red ocher from a holder attached to his quiver and shapes it around the back of the dart as a counterweight. Then he takes the petals of a white flower and packs them around the ocher to smooth the dart’s path through the blowpipe.

He raises the pipe to his mouth and, aiming at the monkey, puffs his cheeks and blows, seemingly with little effort. The dart hits the monkey square in the chest. The curare, a muscle relaxant that causes death by asphyxiation, does its work, and within several minutes the monkey, unable to breathe, tumbles to the forest floor. Shishu swiftly fashions a jungle basket from leaves and vine, and slings the monkey over a shoulder.

By the end of the morning, he’ll kill another monkey and a large black-feathered bird. His day’s hunting done, Shishu heads back to the maloca, stopping briefly at a stream to wash away the mud from his body before entering the hut.

Magna is sitting on a log outside the maloca when we return. It’s a favorite spot for socializing: “The men and women work hard for about four or five hours a day and then relax around the maloca, eating, chatting and sometimes singing,” she says. “It’d be an enviable life except for the constant tension they feel, alert for a surprise attack even though their enemies live far away.”

I see what she means later that afternoon, as I relax inside the maloca with Shishu, Maya, Ta’van and Monan, the clan’s friendliest woman. Their voices tinkle like music as we men sip the herbal drink and the women weave baskets. Suddenly Shishu shouts a warning and leaps to his feet. He’s heard a noise in the forest, so he and Ta’van grab their war clubs and race outside. Jumi and I follow. From the forest we hear the familiar password, “Eh-heh,” and moments later Tatchipan and another clan member, Marebo, stride into the clearing. False alarm.

Next morning, after I’ve performed the haka yet again, Maya hushes the noisy warriors and sends them out to fish in dugouts. Along the river they pull into a sandy riverbank and begin to move along it, prodding the sand with their bare feet. Ta’van laughs with delight when he uncovers a buried cache of tortoise eggs, which he scoops up to take to the hut. Back on the river, the warriors cast vine nets and quickly haul up about 20 struggling fish, some shaded green with stumpy tails, others silvery with razor sharp teeth: piranha. The nutritious fish with the bloodthirsty reputation is a macabre but apt metaphor for the circle of life in this feisty paradise, where hunter and hunted often must eat and be eaten by each other to survive.

In this jungle haunted by nightmarish predators, animal and human, the Korubo surely must also need some form of religion or spiritual practice to feed their souls as well as their bellies. But at the maloca I’ve seen no religious carvings, no rain forest altars the Korubo might use to pray for successful hunts or other godly gifts. Back at the base that night, as Jumi sweeps a powerful searchlight back and forth across the river looking for intruders from downriver, Magna tells me that in the two years she’s tended to clan members, she’s never seen any evidence of their spiritual practice or beliefs. But we still know too little about them to be sure.

The mysteries are likely to remain. Possuelo refuses to allow anthropologists to observe the clan members firsthand— because, he says, it’s too dangerous to live among them. And one day, perhaps soon, the clan will melt back into the deep jungle to rejoin a larger Korubo group. Maya and her clan broke away a decade ago, fleeing toward the river after warriors fought over her. But the clan numbers just 23 people, and some of the children are approaching puberty. “They’ve told me they’ll have to go back to the main group one day to get husbands and wives for the young ones,” says Magna. “Once that happens, we won’t see them again.” Because the larger group, which Possuelo estimates to be about 150 people, lives deep enough in the jungle’s exclusion zone that settlers pose no threat, he’s never tried to make contact with it.

Possuelo won’t bring pictures of the outside world to show the Korubo, because he’s afraid the images will encourage them to try to visit white settlements down the river. But he does have photographs he’s taken from a small airplane of huts of still uncontacted tribes farther back in the Javari Valley, with as few as 30 people in a tribe and as many as 400. “We don’t know their tribal names or languages, but I feel content to leave them alone because they’re happy, hunting, fishing, farming, living their own way, with their unique vision of the world. They don’t want to know us.”

Is Sydney Possuelo right? Is he doing the isolated tribes of Brazil any favors by keeping them bottled up as premodern curiosities? Is ignorance really bliss? Or should Brazil’s government throw open the doors of the 21st century to them, bringing them medical care, modern technology and education? Before I left Tabatinga to visit the Korubo, the local Pentecostal church’s Pastor Antonio, whose stirring sermons attract hundreds of the local Ticuna Indians, took Possuelo to task. “Jesus said, ‘Go to the world and bring the Gospel to all peoples,’ ” Pastor Antonio told me. “The government has no right to stop us from entering the JavariValley and saving the Indians’ souls.”

His view is echoed by many church leaders across Brazil. The resources of the exclusion zones are coveted by people with more worldly concerns, as well, and not just by entrepreneurs salivating over the timber and mineral resources, which are worth billions of dollars. Two years ago more than 5,000 armed men from the country’s landless workers movement marched into a tribal exclusion zone southeast of the JavariValley, demanding to be given the land and sparking FUNAI officials to fear that they would massacre the Indians. FUNAI forced their retreat by threatening to call in the military.

But Possuelo remains unmoved. “People say I’m crazy, unpatriotic, a Don Quixote,” he tells me when my week with the Korubo draws to a close. “Well, Quixote is my favorite hero because he was constantly trying to transform the bad things he saw into good.” And so far, Brazil’s political leaders have backed Possuelo.

As we get ready to leave, Ta’van punches his chest, imitating the haka, asking me to perform the dance one last time. Possuelo gives the clan a glimpse of the outside world by trying to describe an automobile. “They’re like small huts that have legs and run very fast.” Maya cocks her head in disbelief.

When I finish the war dance, Ta’van grabs my arm and smiles a farewell. Shishu remains in the hut and begins to wail, anguished that Possuelo is leaving. Tatchipan and Marebo, lugging war clubs, escort us down to the river.

The canoe begins its journey back across the millennia, and Possuelo looks back at the warriors, a wistful expression on his face. “I just want the Korubo and other isolated Indians to go on being happy,” he says. “They have not yet been born into our world, and I hope they never are.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.