Photos From the Coldest City on Earth

What’s it like to live and work in the coldest inhabited place on Earth? Photographer Amos Chapple shares his stories from the frozen cities of Siberia

For most people, Oymyakon—the world's coldest permanently settled area, located a few hundred miles from the Arctic Circle in the Russian tundra—wouldn't be a top-of-the-list travel destination. But for New Zealand photographer Amos Chapple, it offered an opportunity he couldn't refuse. Working as an English teacher in Russia to support his travel photography, Chapple viewed a trip to Oymyakon—and its nearest city, Yakutsk (576 miles away)—as a chance to embark on a unique photography project.

"There's this idea that to be seen as a serious photographer, you have to seek out suffering in the world," says Chapple, who worked as a news photographer in New Zealand for years before branching into travel photography. "I wanted to take a photojournalistic approach to stories that are not negative, not nasty. I was looking for a headline that I could hang a picture story on, and coldest place in the world is a good example of that."

Temperatures in Yakutsk peak at around minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit during the month of January, but Chapple describes the city as cosmopolitan and surprisingly wealthy. Settled in large part due to an abundance of natural resources around it (diamonds, oil and gas are all plentiful), Yakutsk is an economically vibrant place. Still, it's extremely remote: six time zones away from Moscow, there is a small airport but no railway, and the town boasts but one major road leading in and out of it. Known as the "Road of Bones," it was built by gulag inmates under Stalin's regime.

During the Soviet era, the government paid workers bonuses to move to climatically unappealing areas. The promise of riches enticed thousands of workers to Yakutsk, where they mingled with the indigenous ethnic population, known as the Yakuts, and laborers who remained from the gulag system to turn the provincial outpost into a major regional city. Today, Alrosa—the corporate giant that supplies 20 percent of the world's rough diamonds—is headquartered in the region. Because of the city's abundance of natural resources, and its resident's extra wealth from working in the coldest city on Earth, Yakutsk is an expensive place to live in and to visit. Women wear a winter uniform of fur coats, which entice Siberian burglars even more than stashes of money, since they can be resold for thousands of dollars. "If you say that your family is Siberian, quite probably you are rich, just from doing pretty simple work," Chapple says.

It's also an expensive city to sustain: emergency fuel shipments to Siberian cities cost Russia an estimated $500 million per year. According to Clifford Gaddy, an economist with the Brookings Institution who co-authored the book The Siberian Curse, it would be less expensive for the country to simply fly laborers into Siberia to extract the natural resources and then fly them out again instead of paying to keep Siberian cities functioning. Building in Yakutsk is also challenging because the city is constructed on continuous permafrost—13 feet below the surface, Yakutsk's soil holds steady at 17 degrees Fahrenheit, no matter the temperature of the air. Normally, the soil (a combination of sand and frozen ice) is hard as a rock and nearly impenetrable, but around the edges, and when the ice begins to warm, the soil thaws to a powdery consistency. If a building is constructed on thawing permafrost—or the heat from the structure speeds thawing—its foundation can quickly become unstable. To account for this challenge, every building in Yakutsk is built on underground stilts.

Contrasted against Yakutsk's relatively cosmopolitan comforts, the villages of the greater Sakha Republic (of which Yakutsk is the capital) are frozen hamlets. To get to Oymyakon, which set the record in 1933 as the coldest place on Earth with a temperature of minus 90 degrees Fahrenheit, Chapple had to travel for two days via a combination of shared vans and hitchhiking. At one point, he was stranded for two days at a gas station. "I was eating reindeer meat for two days," Chapple says, recalling the small cafe and teahouse, ironically named Cafe Cuba, that served as his sole option for food during that time. "Reindeer was the staple meat of the tundra."

Reindeer isn't the only thing that inhabitants of the coldest region on Earth eat, but their diet skews meat-heavy. Chapple also ate a dish of macaroni pasta and frozen chunks of horse blood, as well as a Yakutian specialty of thinly shaved frozen fish. "It's basically like frozen sashimi, and it's divine," he says. "Somehow the texture of the frozen fish, with the warm bits at the end, is very distinctive and delicious."

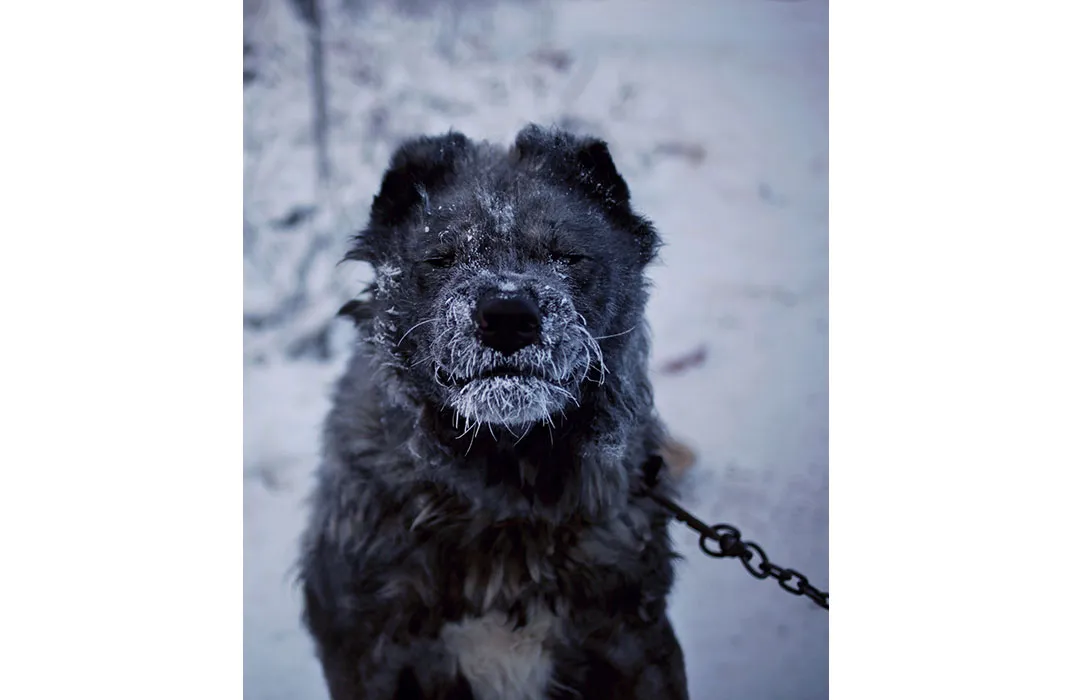

When he arrived in Oymyakon, whose population hangs at around 500 permanent inhabitants, Chapple was struck by the emptiness of the place. "The streets were just empty. I had expected that they would be accustomed to the cold and there would be everyday life happening in the streets, but instead people were very wary of the cold," he says. "It felt extremely desolate. It wasn't, but everything was happening indoors, and I wasn't welcome indoors." In the hours Chapple spent wandering the village streets, his main companions were street dogs or village drunks (alcoholism is rampant in Oymyakon).

Still, life in the village goes on. Schools don't close unless the temperatures fall below minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit. Farmers bring their cows to the village's watering hole—a "thermal" spring that stays a few degrees above freezing—then lead them back to their insulated stables. The thermal spring is the village's lifeblood, its entire reason for existence: reindeer herders would visit the spring in order to hydrate their herds, returning again and again until the village became a permanent settlement (Oymyakon literally means "unfrozen water").

Living in the coldest inhabited place on Earth does have some distinct drawbacks, however. Bathrooms are mostly outdoors, because indoor plumbing presents a challenge due to frozen pipes. Residents have cars, but must leave them running outside, sometimes overnight, so the mechanics don't freeze up. Even so, sometimes more extreme measures are necessary. "A guy I was staying with left his car running all night, but even so, in the morning, the drive shaft was completely frozen. Without any ceremony, he pulled out a little flamethrower, went under the truck and started fanning the bottom of his truck with a flamethrower," Chapple says. "It's part of the toolkit [for living in Oymyakon], a little flamethrower."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)