Preparing for a New River

Klallam tribal members make plans for holy ancestral sites to resurface after the unparalleled removal of nearby dams

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Elwha-River-tribal-youths-631.jpg)

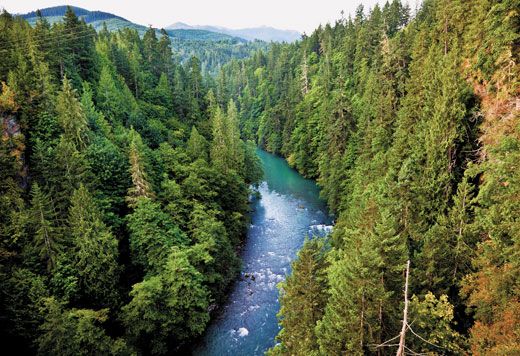

The turquoise, snow-fed Elwha River crashes through the cedar forests of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. In the early 1900s, the river was dammed to generate electricity for a nearby logging town, but the dams devastated the Klallam Indians who had lived along the Elwha for thousands of years. The structures blocked the river’s salmon runs and flooded a sacred place on the riverbanks considered the tribe’s creation site.

Now the two antique dams are being dismantled—the largest and most ambitious undertaking of its kind in U.S. history. Demolition began this past September and will take three years to complete. It will free up some 70 miles of salmon habitat and allow the fish to reach their upstream spawning grounds again. Scientists expect a boom in bald eagles, bear and other creatures that gorge on salmon.

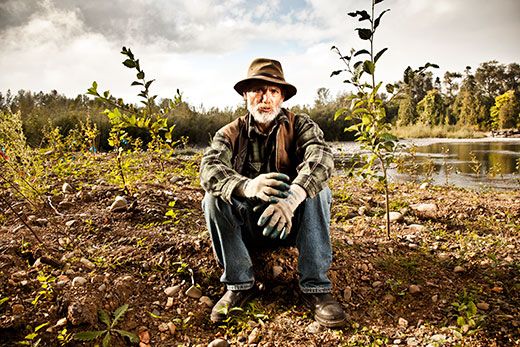

The Klallam people, who have lobbied for the dams’ removal for decades, are preparing their children for the river’s renaissance. The Elwha Science Education Project, hosted by NatureBridge, an environmental education organization, has held camps and field trips for youths from the Lower Elwha Klallam and other tribes to acquaint them with the changing ecosystem—and maybe spark an interest in watershed science.

“We want them to say, ‘I could be fixing this river,’” says Rob Young, the coastal geoscientist who designed the program. “‘I could be helping it heal. I could be uncovering sacred sites. That can be me. And it should be me.’”

When I visited a camp, held in Olympic National Park, some of the middle schoolers already knew the Elwha’s saga well; others couldn’t spell the river’s name. But for a week, all of them were immersed in ecology and ancestral culture. They went on a hike to a nearby hot spring. They listened to tribal stories. They played Plenty o’ Fish, a rather cerebral game in which they weighed a fisheries biologist’s advice about salmon harvests against a greedy grocery store agent’s bribes. They studied how their ancestors pounded fern roots into flour, made snowberries into medicine and smoked salmon over alder wood fires.

The kids helped repot seedlings in a park nursery where hundreds of thousands of plants are being grown to replant the river valley after the reservoirs are drained. The nursery manager, Dave Allen, explained how important it is that invasive plants don’t elbow out the native species when the soil is exposed and vulnerable. “You guys will have lived your lives and this will still be evolving and changing into forest,” Allen told the kids. “When you are old people—older than I am, even—you’ll still be seeing differences.”

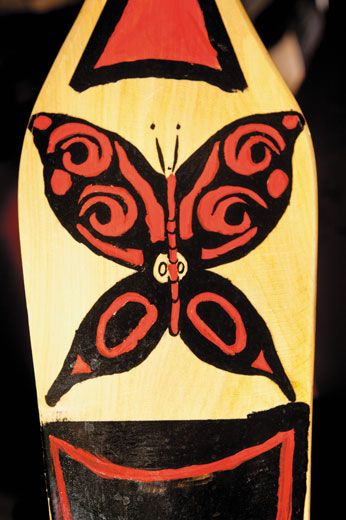

The highlight of the week was a canoe journey and campout across Lake Crescent. The kids occupied two huge fiberglass canoes. Each crew had dark designs on the other, with much splashing between the boats, and they wanted to race, but their competitive passions outstripped their paddling skills and the canoes turned in slow circles.

Dinner that night, cooked over a fire among the fragrant cedars, was native foods, supplemented by teriyaki chicken bused over from the dining hall. The steamed stinging nettles tasted something like spinach. The kids gagged over the raw oysters, but when the counselors cooked the shellfish on the campfire rocks, everybody asked for seconds.

Afterward, the children sang one of the tribe’s few surviving songs. Far from an enthusiastic paddling anthem, the haunting “Klallam Love Song” is about absence, longing and the possibility of return. Tribal members would sing it when their loved ones were away. The words are simple, repeated over and over. “Sweetheart, sweetheart,” they would cry. “You are so very far far away; my heart aches for you.”

Abigail Tucker wrote recently about beer archaeology and Virginia’s bluegrass music. Brian Smale is based in Seattle.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.