The Remarkable Cave Temples of Southern India

Deccan’s intricate monuments, many of which are carved into cliffs, date back to the sixth century

As an architecture student in Melbourne, Australia, in the 1960s, I’d hardly ever seen a building older than a hundred years, let alone confronted a civilization of any antiquity. That changed resoundingly when I traveled to India while still at college.

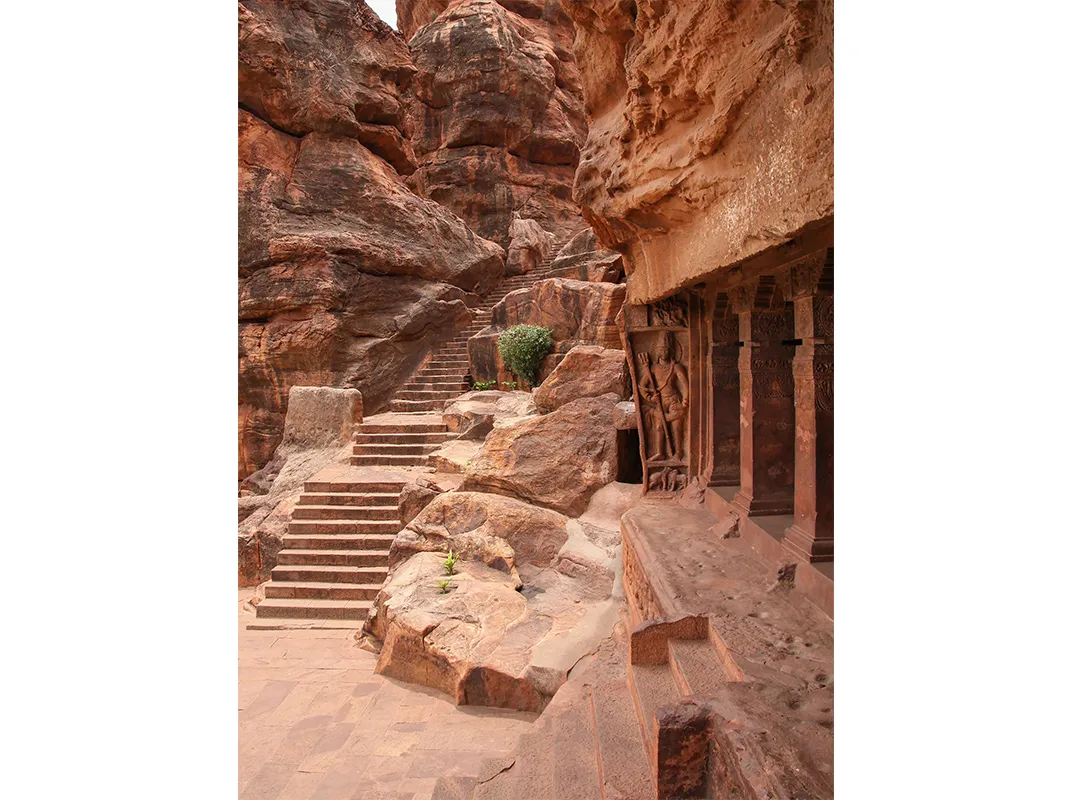

During my wanderings in the subcontinent, I somehow got to hear of a remote town called Badami with wonderful temples, just the sort of place worth seeking out, though I’d never read anything about it. I checked, and there it was on the map; there was even a train connection. Taking a pony cart from Badami station into town, I marveled at the dramatic landscape of the Deccan region. Red sandstone cliffs, shattered by deep fissures into rugged profiles, reared over mud-walled houses splashed with ocher paint.

After dropping my luggage at the local rest house, I wandered through the town and came upon a vast reservoir filled with vividly green water. At one end, women washed clothes by beating them on stone steps; at the other, a small temple with a veranda jutted invitingly into the water. High above the tank were cliffs punctuated with grottoes; I later realized these were artificial cave temples cut into the rock. On the summit of the cliffs opposite rose a freestanding temple fashioned out of the same sandstone as the rock itself, perfectly blending into its natural setting. Quite simply, this was the most intriguingly beautiful place I’d ever seen; 50 years later, having traveled to so many places around India, I haven’t changed my mind.

The trip to Badami contributed to a life-changing decision: to move to London and study Indian art and archaeology. Only then did I learn that Badami had been the capital of the Chalukyas, a line of kings who ruled over most of the Deccan for almost 200 years between the sixth and eighth centuries. One of a succession of dynasties in this part of India, the Chalukyas attracted my attention because they were great patrons of architecture and art, overseeing a transition from rock-cut architecture to freestanding, structural architecture, all embellished with magnificent carvings. No one in London in the early 1970s had much idea about the Chalukyas and their art. This was hardly surprising since no example of Chalukya sculpture had found its way into a European or American collection. The same is largely true today. Only by making a journey to Badami (about 300 miles from the city of Bangalore) and nearby sites can the outstanding contribution of Chalukya architects and sculptors be appreciated.

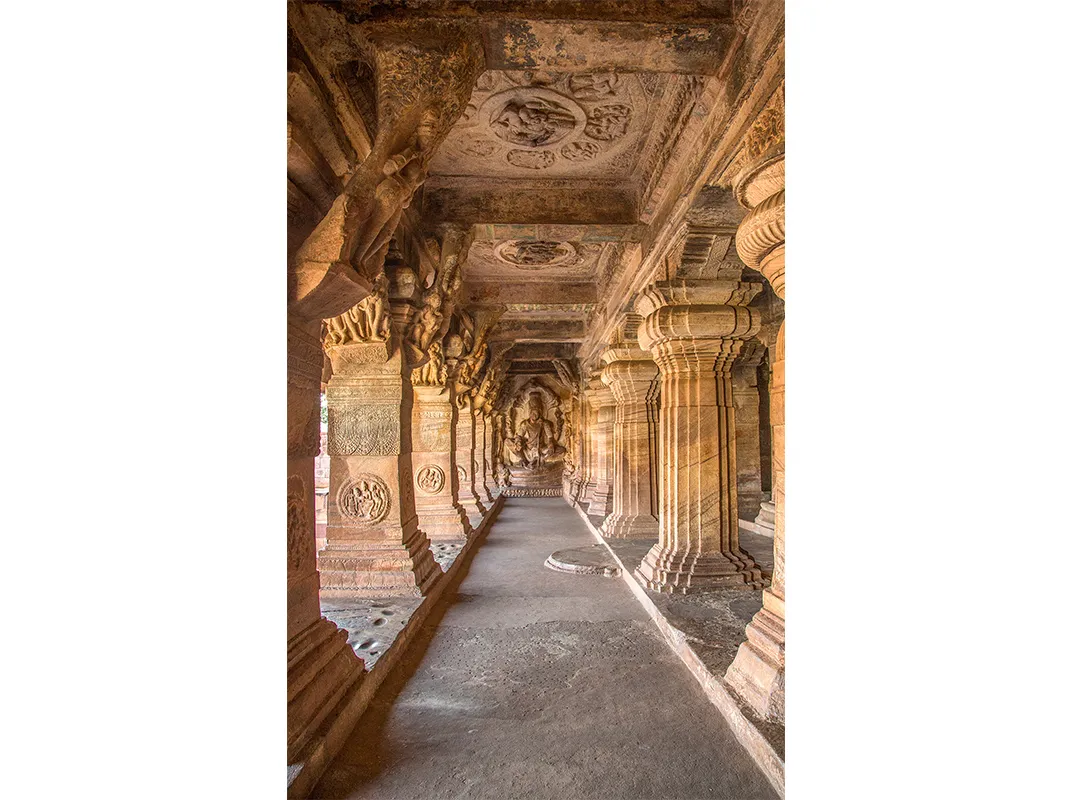

Any exploration of Chalukya art best begins in Badami, still the only town in this part of the Deccan with acceptable accommodations. Following the route that skirts the maze of streets and houses, you arrive at a stepped path built into the cliffs on the south side of the reservoir. Dodging the resident monkeys if possible, you can climb to the top and enjoy a spectacular panorama across the water. Opening to one side of the steps are four cave temples. The lowest is dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, as is evident from a majestic image of the eighteen-armed, dancing god carved onto the cliff face immediately outside. Once inside, you may think you’ve entered an actual structure, with lines of columns and beams supporting a flat ceiling. But this impression is deceptive; all these features are monolithic, hewn deeply into the cliff. A tiny chamber cut into the rear of the hall has an altar with a lingam, the phallic emblem of Shiva. A stone representation of Nandi, the bull that served as the god’s mount, is placed in front.

Up the steps is the largest of the cave temples, also furnished with columns and beams, as in a constructed hall. This is consecrated to Vishnu, who is depicted in various forms in magnificent panels carved onto the end walls of the front veranda: The god is seated on the cosmic serpent; he appears in his man-lion incarnation, with the head of a ferocious animal, leaning on a club; and in yet a third appearance the god is shown with one leg kicked high, pacing out the three steps of cosmic creation. Angled brackets “supporting” the beams have reliefs of human couples in tender embrace, posed beneath flowering trees. This auspicious motif was evidently intended to provide Vishnu’s home with magical protection. An inscription engraved on an interior column explains that the temple was commissioned by a Chalukya prince in 578, making it the earliest dated Hindu cave temple in India.

More remarkable Chalukya architecture and art is only about an hour’s drive away from Badami, in the village of Aihole (pronounced eye-HO-lee). When I first made this excursion decades ago, there were no cars, only public buses, and it took the better part of a day. I may have been one of the first foreigners to reach Aihole. On a stroll outside the town with someone I met who could muster some English, I came across a woman working on road repairs, carrying earth in a metal bowl on her head. When told I came from London, she asked if this unfamiliar place could be reached by bus. In a way it could, since road travel across the Middle East was still possible then!

Aihole in those early days was a bewildering mix of past and present, with village houses built right up to, and even into, ancient temples. Some temples bore the names of their inhabitants rather than those of the divinities for which they were originally built. All the Aihole temples are constructed of sandstone blocks placed one upon the other without any mortar. The oldest stands atop the Meguti hill that overlooks the town, with a faraway view of the Malaprabha River flowing through a lushly irrigated valley. This is not a Hindu monument, but Jain. This ancient, austere religion, espousing nonviolence and giving religious prominence to the salvation of the soul rather than to gods, survives today among minority communities in different parts of India, including the Deccan.

The sandstone exterior of the Meguti Hill temple, though now ruined, is clearly divided into three vertical parts: a basement running along the bottom; walls above that rhythmically project outward and recess inward, each change of plane marked by a slender pilaster; and at the top, a parapet with a line of small curved and arched roofs. As I was to later learn, these features are typical of the Dravidian temple style of southern India. Set into the wall, an inscribed stone panel mentions the history and exploits of Pulakeshin, the Chalukya ruler who ordered the temple be erected in 634. Verses composed by the court poet Ravikirtti praise the rule as “almost the equal of Indra [god of the heavens].”

Other, better-preserved Chalukya monuments in Aihole are in town. They are no longer encroached upon by houses, as when I first saw them, but set in a grassy compound protected by barbed wire. The largest, the Durga temple, is unusual in appearance since its plan has a semicircular end. This peculiar shape reminded some ancient Indian authors of an elephant’s backside, though that was unlikely to be the intention of the temple’s designer.

Walking along the shaded veranda that surrounds the temple, you can marvel at a series of sculpted panels set into the side walls. They portray a range of Hindu divinities: Shiva with the bull Nandi; Vishnu in his man-lion and boar incarnations; the same god with his eagle mount, Garuda; and the goddess Durga violently plunging her trident into the neck of the buffalo demon that had threatened the power of all the gods. In spite of this last panel, the temple was not dedicated to the goddess Durga; its name derives instead from durg, or fort, since in troubled times the temple came to be used as a lookout. Rising on its roof is a dilapidated tower with curved sides, once topped by a gourdlike ribbed finial, now fallen on the ground nearby. This type of tower is typical of the Nagara temple style of northern India.

Comparing the Meguti hilltop temple and the Durga temple in town, I understood that builders and craftsmen at Aihole had been brought from different parts of India to work for the Chalukya kings. How this had happened is partly explained by the location of the Chalukyas in the heart of the Deccan, wedged between northern and southern India. Nowhere else in the country are temples in such divergent styles built right next to each other. These contrasts are on display at Pattadakal, a village on the bank of the Malaprabha, roughly midway between Badami and Aihole. On my 1960s visit, the only way to reach Pattadakal from Aihole was to walk for three hours beside the Malaprabha, risking savage dogs and wading through the river at the end. Visitors today can reach Badami by car in little more than a half hour.

The Pattadakal temples represent the climax of Chalukya architecture in the first half of the eighth century. Larger and more elaborately embellished than those in Badami and Aihole, the Pattadakal monuments are all dedicated to Shiva. Built close to one another, they face east toward the Malaprabha, which here makes a turn to the north, with the water appearing to flow toward the distant Himalaya, the mountain home of Shiva. The two grandest Pattadakal temples were financed by sister queens in about 745 to celebrate the military victory of their lord, Vikramaditya, over the rival Pallava kings to the south. A notice of their bequest is incised onto a nearby, freestanding sandstone column. They would have been among the most impressive Hindu monuments of their day.

The temples of the two queens are laid out in identical fashion, each with a spacious hall entered through covered porches on three sides. The hall interiors are divided into multiple aisles by rows of columns, their sides covered with relief carvings illustrating popular legends, such as those of Rama and Krishna. The central aisle in each temple leads to a small sanctuary accommodating a Shiva

lingam, but only in the Virupaksha temple is there any worship. A priest is in attendance to accept contributions from tourists in their role as pilgrims. The outer walls of both temples have multiple projections marked by a sculpted figure of a god. The profusion of carvings amounts to a visual encyclopedia of Hindu mythology. Walls on either side of the front porch of the Virupaksha temple, for instance, have a matching pair of panels, one of Shiva appearing miraculously out of the lingam and the other of Vishnu pacing out the cosmos. Above the walls of each temple is a tower in the shape of a pyramid soaring upward to the heavens. These typical Dravidian-style towers contrast markedly with other temples at Pattadakal that have curving towers in the Nagara manner.

Pattadakal is now a UNESCO World Heritage site under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India, which proudly displays the inscription on the signboard at the entrance to the landscaped compound. But when I was first here, the village houses were built right up to the ancient monuments. And I’ll never forget that in the doorway of one temple was a tailor briskly pedaling away at his Singer sewing machine.

One Chalukya complex that still retains something of its original sacred context is Mahakuta, on a side road running between Pattadakal and Badami. Judging from a column discovered here with an inscription dated 597, the shrines at Mahakuta, all dedicated to Shiva, have been in continuous worship for almost 1,400 years. They are grouped around a small rectangular pond fed by a natural spring; local youths delight in jumping into the water, as I also did on several occasions. The sound of the splashing agreeably complements the music and prayers that drift out of the nearby temples. Here, too, architects and craftsmen from different parts of India must have been employed since the temples were built in both Nagara and Dravidian styles. While we know nothing of the origin and organization of the different guilds of workmen, they were certainly accorded high status in Chalukya times.

By now it must be clear that I rapidly succumbed to the allure of the rugged Deccan landscape and the architectural brilliance of the Chalukya temples, let alone the extraordinary beauty of the sculptures. Not only were these among the earliest Hindu monuments in India, they were also remarkably well preserved. When I had to select a topic for my dissertation at the University of London, I came quickly to the decision to focus on the Chalukya period.

Which is how I came to return to the Deccan in the winter of 1970, accompanied by two junior architects in order to make measured plans, elevations and sections, not with modern electronic devices but with old-fashioned tape measures and stepladders. One of my team’s first publications was an article about the main temple at Mahakuta. Since we had been greatly helped in our fieldwork by a local priest, I thought I’d bring him a copy. But when I arrived at Mahakuta almost a decade later, this particular priest was nowhere to be found; there was only a local boy, who spoke no English, officiating. I showed him the article, which had drawings and photographs. He immediately recognized his temple. He opened the sanctuary door, lit a lamp and saluted the lingam. He then took my article and presented it as an offering to the god. And so in this single gesture, I was briefly transformed from a fledgling scholar into a true devotee of Shiva.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.