Five Places Where You Can Still See Remnants of the Great Chicago Fire

Though the city was completely rebuilt within two years, you can still see evidence of the fire that destroyed it

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/48/df/48dfb52b-54d9-4902-a274-6f1c80478400/cf_finial4.jpg)

On October 8, 1871, the city of Chicago became an inferno. One spark inside a barn at the O’Leary residence on DeKoven Street sent flames whirling through the city, pushed on by hellish winds and fed by 3.3 square miles of wooden buildings. When the city emerged from the flames on October 10, about 300 people were dead, 90,000 were homeless and more than 17,000 buildings were destroyed.

To this day, no one knows for sure exactly what started the fire in the O'Leary barn – an accident, vandalism or a stray spark from a nearby chimney. And while folklore points the finger at Mrs. O'Leary's cow for kicking over a lantern, Catherine O’Leary and her cow were officially exonerated of blame by the Chicago City Council in 1997, more than 100 years later.

Few spots downtown survived the fire, and some of the debris was actually pushed into Lake Michigan, creating what we now know as Grant Park. The most famous of the architectural survivors, though, are the Water Tower and Pumping Station, and for a very good reason.

“One of the reasons the water tower was so important,” Russell Lewis, chief historian and executive vice president at the Chicago History Museum, told Smithsonian.com, “was that [after the fire] people did not have any physical geographical orientation to know where their home was or where they were, except by orienting to the water tower. They could say, ‘OK, from my porch the water tower looked like this,’ so they would try to approximate that location. Otherwise, all the physical boundaries were burned.”

In true Chicago spirit, though, within a couple years the city was almost completely rebuilt. “It was a new city,” Lewis said. “If you didn’t know there had been a fire, you’d have no idea there was one.” But if you know where to look, evidence of the fire lurks just beneath the polished surfaces we see today. These five spots are little-known remnants of the Great Chicago Fire—places where you can still see the trauma underneath the cover of a brand new city.

Char Marks, St. James Cathedral

When the church bells of St. James Cathedral at the corner of Wabash and Huron rang on the evening of Sunday, October 8, it wasn’t for religious services. Bells across the city rang out as a warning to the surrounding neighborhoods that a fire had broken out. When the fire was over, the only remaining parts of the church were the stone walls, a Civil War memorial in the narthex and the bell tower. According to the Driehaus Museum, if you stand in front of the church and look up today, the top of the bell tower is still shrouded in black char marks left behind as a memorial to this tragic chapter in the city’s history.

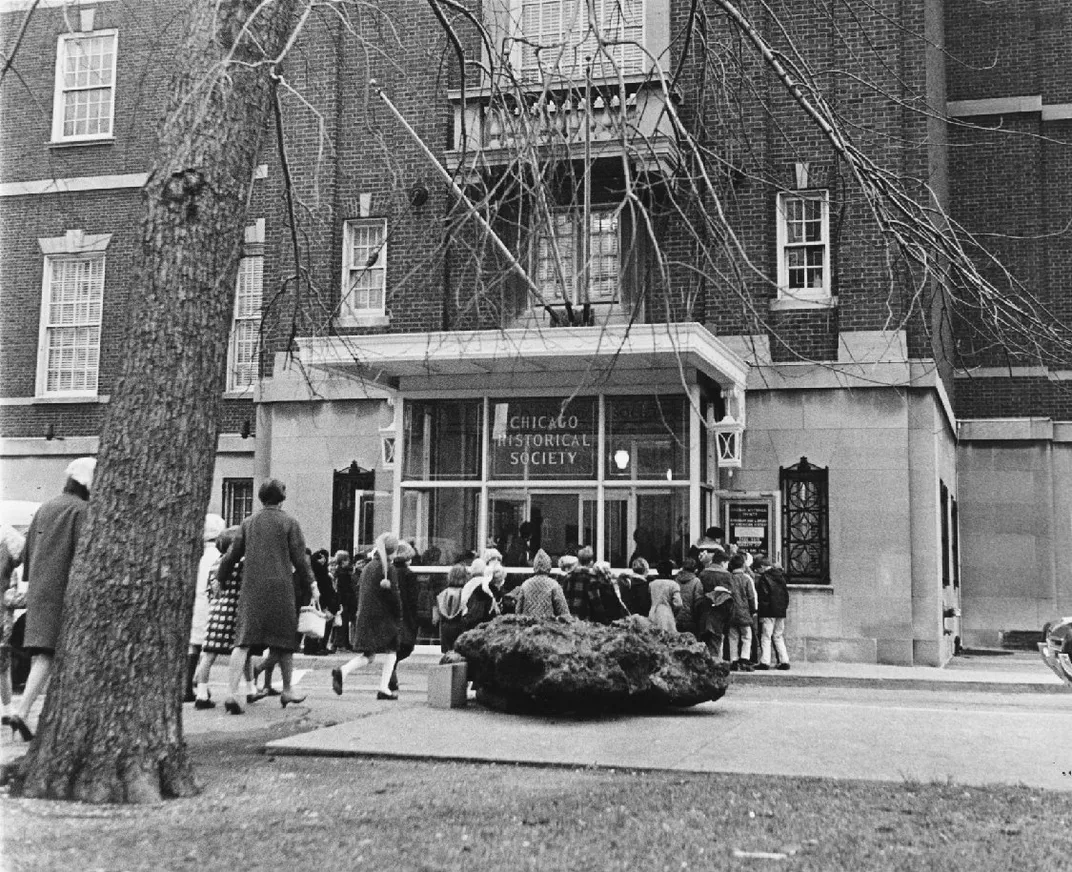

Fused Metal, Chicago History Museum

Tucked into some hedges behind the Chicago History Museum, a huge lump of melted metal sits sinking into the ground. “It’s the remnants of a hardware store,” Lewis said. “All of the iron and metal fused together leaving a very big, heavy blob.” The metal blob was moved behind the building in the 1970s after spending years in front of the museum. It’s not as easy to spot now, so ask someone to point it out.

Courthouse Finial, Lincoln Park

Similar to the bells in the cathedral, the bell in the city’s first courthouse at Clark and Randolph began ringing to warn residents of the fire. The bell continued to ring for the next five hours, until the building’s cupola collapsed, Lewis said. The courthouse roof was accented on the east and west wings with about 24 urn-shaped limestone finials. One of them was salvaged from the burnt rubble and installed in Lincoln Park, close to the corner of Clark and Armitage. It currently sits in front of the Lincoln Park Zoo.

The Beginning, Chicago Fire Academy

Consider this building the ground zero of the Great Chicago Fire. The Robert J. Quinn Fire Academy was built at DeKoven and Jefferson, on the site of the O’Leary house and barn. “That’s the poetic justice,” Lewis said. “They built the academy to train firefighters on the site.” Outside, a famous sculpture by Egon Weiner meant to represent a flame commemorates the historical event. Inside, visitors can find a firefighter emblem on the floor emblazoned with “1871”— this emblem marks the exact location of the O’Leary barn, where the fire began.

Graveyard Crypt, Lincoln Park

According to Lewis, Lincoln Park was originally a cemetery. It was bordered on one end by North Avenue, which at the time of the fire marked the northern boundary of the city. In 1865, the city decided to move the cemetery directly outside the city limits. When the fire came in 1871, the city was still in that process. “They hadn’t yet moved all the bodies and there were some open graves in this area that people hid in to escape the fire,” Lewis said. Now, all that remains (aside from an estimated 12,000 bodies still buried in unmarked graves from the original cemetery) is one crypt, for a wealthy hotelier named Ira Couch, which survived the fire and marks the area as a former cemetery.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)