Resurrecting the Czar

In Russia, the recent discovery of the remains of the two missing Romanov children has pitted science against the church

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Romanovs-Czar-monarchist-631.jpg)

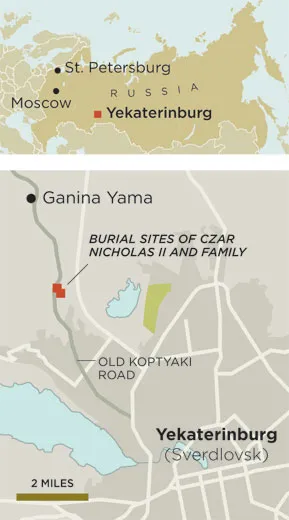

Valentin Gribenyuk trudges ahead of me through a birch and pine forest outside Yekaterinburg, Russia, waving oversize mosquitoes from his neck and face. The woods close in around us as we follow a trail, stepping over rotting tree trunks and dark puddles. “Right here is the Old Koptyaki Road,” he says, pointing to a dirt and gravel path next to a gas pipeline. “This is where the assassins drove their truck.” We stop at a spot where nine timbers are embedded in the ground. A simple wooden cross stands vigil. “The bodies were found buried right [at the site marked by] these planks.”

Like many Russians, Gribenyuk, a 64-year-old geologist, has long been obsessed with one of Russia’s most infamous crimes. He now finds himself at the center of the latest controversy surrounding the grisly, world-shattering events of July 17, 1918.

Around 2 a.m. on that day, in the basement of a commandeered house in Yekaterinburg, a Bolshevik firing squad executed Czar Nicholas II, his wife, Alexandra, the couple’s five children and four attendants. The atrocity ended imperial rule in Russia and was the signature act of a new Communist regime that would brutalize its citizens for most of the 20th century.

The murder of Czar Nicholas Romanov and his family has resonated through Soviet and Russian history, inspiring not only immeasurable government coverups and public speculation but also a great many books, television series, movies, novels and rumors. Yet if it has been an open secret that the Communists had dispatched the Romanovs, there was genuine mystery, apparently even within the government, concerning the whereabouts of the royal remains.

Then, in May 1979, a handful of scientists searching clandestinely in the woods outside Yekaterinburg, a city of 1.5 million residents 900 miles east of Moscow in the Ural Mountains, found the long-decayed skeletons of nine people, including three children. But the scientists didn’t divulge their secret until 1990, as the USSR teetered toward collapse. As it happened, a powerful new forensic identification method based on DNA analysis was just coming into its own, and it soon showed that the remains of five of the nine persons uncovered were almost certainly those of the czar, his wife and three of their children; the others were the four attendants.

The story, of course, has been widely reported and celebrated as a sign of post-Soviet openness and as a triumph of forensic science. It’s also common knowledge that the Russian Orthodox Church and some prominent Romanov descendants dispute those findings. The church and the royals—both of which were suppressed by the Soviets—are longtime allies; the church, which regarded the czar as a near-divine figure, canonized the family in 2000, and a movement to reinstate the monarchy, though still small, does have its passionate adherents. Ironically, both the church and some in the royal family endorse an older, Soviet recounting of events that holds that the Romanov remains were disposed of elsewhere in the same forest and destroyed beyond recovery. The 1990 forensic findings, they contend, were flawed.

But that became harder to accept after a July day in 2007.

That’s when a team of investigators working with Gribenyuk uncovered the remains of two other Romanovs.

Nicolay Alexandrovich Romanov was born near St. Petersburg in 1868, the son of Crown Prince Alexander and Maria Feodorovna, born Princess Dagmar of Denmark. His father ascended the throne as Alexander III in 1881. That year, when Nicolay was 13, he witnessed the assassination of his grandfather, Alexander II, by a bomb-throwing revolutionary in St. Petersburg. In 1894, as crown prince, he married Princess Alix of Hesse, a grand duchy of Germany, granddaughter of Queen Victoria. Nicholas became czar the same year, when his father died of kidney disease at age 49.

Nicholas II, emperor and autocrat of all the Russias, as he was formally known, reigned uneventfully for a decade. But in 1905, government troops fired on workers marching toward St. Petersburg’s Winter Palace in protest against poor working conditions. About 90 people were killed and hundreds wounded that day, remembered as “Bloody Sunday.” Nicholas didn’t order the killings—he was in the countryside when they took place—and he expressed sorrow for them in letters to his relatives. But the workers’ leader denounced him as “the soul murderer of the Russian people,” and he was condemned in the British Parliament as a “blood-stained creature.”

He never fully recovered his authority. In August 1914, following the assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Nicholas plunged the unprepared nation into World War I. Supply lines collapsed; food shortages and unrest spread through Russia. Hundreds of thousands died in trenches under withering artillery and machine-gun fire by the German and Austro-Hungarian armies. On March 12, 1917, soldiers in St. Petersburg mutinied and began seizing imperial property. Three days later, facing the Russian Parliament’s demand that he quit, and fearing an outbreak of civil war, Nicholas abdicated the throne. He was evacuated to the Ural Mountains, where the family was put under house arrest.

The American journalist and historian Robert K. Massie, author of the best-selling biography Nicholas and Alexandra, described the czar as an inept ruler “in the wrong place in history.” But Massie also took note of Nicholas’ “personal charm, gentleness, love of family, deep religious faith and strong Russian patriotism.”

The Bolsheviks, a faction of Marxist revolutionaries led by Vladimir Lenin, seized power that October and moved the family to a two-story house in Yekaterinburg owned by a military engineer, Nikolai Ipatiev. Nine months later, the Romanovs were awakened in the middle of the night, told of advancing White Russians—counterrevolutionary forces, including remnants of the czarist army—and led into the basement. A ten-man execution squad entered the room. Their leader, Yakov Yurovsky, pronounced a death sentence. Nicholas uttered his last words—“What?” or “You know not what you do” (accounts differ)—and the squad opened fire. The shots instantly killed the czar, but some bullets failed to penetrate his daughters’ jewel-encrusted corsets. The young women were dispatched with bayonets and pistols.

State radio announced only that “Bloody Nicholas” had been executed. But rumors that the entire family had been murdered swirled. One week after the killings, the White Russian Army drove the Bolsheviks out of Yekaterinburg. (It would hold the city for about a year.) The White Russian commander appointed a judicial investigator, Nikolai Sokolov, to look into the killings. Witnesses led him to an abandoned iron mine at Ganina Yama, about ten miles outside town, where, they said, Yurovsky and his men had dumped the stripped bodies and burned them to ashes. Sokolov searched the grounds and climbed down the mine shaft, finding topaz jewels, scraps of clothing, bone fragments he assumed were the Romanovs’ (others have since concluded they were animal bones) and a dead dog that had belonged to Nicholas’ youngest daughter, Anastasia.

Sokolov boxed his evidence and took it to Venice, Italy, in 1919, where he tried to present it to Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, the czar’s uncle; the duke refused to show the items to the czar’s exiled mother, Maria Feodorovna, fearing they would shock her. To the end of her life in 1928, she would insist that her son and his family were still alive somewhere. Officials of the Russian Orthodox Church, also in exile, embraced the investigator’s account, including the conclusion that the bodies had been burned at Ganina Yama.

Legend had it that Sokolov’s evidence ended up hidden inside a wall at the New Martyrs Russian Orthodox Church in Brussels. But Vladimir Solovyev, a criminal investigator in the Moscow prosecutor’s office who has worked on the Romanov case since 1991, searched the church and turned up nothing. The evidence, he said, “vanished during the Second World War.”

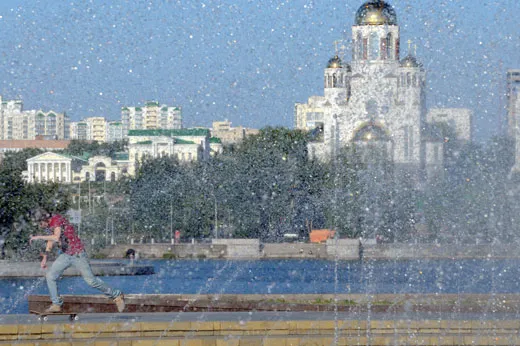

Yekaterinburg is a sprawling industrial city on the banks of the Iset River. Known as Sverdlovsk during Soviet times, Yekaterinburg, like much of Russia, is marked by its Communist past: on Lenin Street, a huge bronze statue of the Bolshevik revolutionary, his arm outstretched, leans toward City Hall, a Stalin-era structure covered with friezes of Soviet workers and soldiers. Inside a crumbling building near the city center, I climbed a stairwell redolent of boiled cabbage to a top-floor apartment, where I met Alexander Avdonin, a geologist who uncovered the truth about the Romanov remains—then kept it secret for a decade.

Avdonin, white-haired and ailing at 78, grew up in Yekaterinburg, not far from the Ipatiev house, where the executions occurred. From the time he was a teenager, he says, he was intrigued by what happened that notorious night. There were, to be sure, many different accounts, but in the one that would eventually pay off for Avdonin, the Bolshevik leader Yurovsky indeed piled the Romanov corpses into a truck and drove to the Ganina Yama mine. But Yurovsky decided that too many people had witnessed the movements of trucks and soldiers during the night. So he later returned to the mine, put the bodies back in a truck and headed for some other iron mines 25 miles away. Five minutes down the road, the vehicle got stuck in mud. It was here, a few miles from Ganina Yama, witnesses said, that Yurovsky and his men hurriedly doused some of the bodies with sulfuric acid and gasoline and burned them. According to Moscow investigator Solovyev, nine bodies were placed beneath some logs and two others in a separate grave. Yurovsky apparently believed that separating family members would help obscure their identities.

“The decision was meant to be temporary, but the White Army was approaching, so that grave would be the final grave,” Solovyev told me.

But where, exactly, was that final site? In 1948, Avdonin got his hands on a diary written by a local Bolshevik official, Pavel Bykov; it had been published in 1926 under the title The Last Days of Czardom. The book—the first public admission by the regime that the entire Romanov family had been executed—suggested that the bodies hadn’t been burned to ash, but rather buried in the forest. By the 1940s, The Last Days had vanished from libraries, presumably confiscated by Soviet authorities, but a few copies survived. Avdonin also read an account by the Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, who said that, in the late 1920s, he had been taken to the burial site—“nine kilometers down the Old Koptyaki Road” from the center of town. Finally, Avdonin came across an account published by Sokolov, the original investigator. It contained a photograph of timbers—likely railroad ties—laid down in the forest; Sokolov described the site marked by the boards as a place where some unidentified corpses had been dumped. “Sokolov interviewed a railroad worker [who] said that a vehicle with corpses in it got stuck in a bog,” Avdonin said. “This worker said that the vehicle, horses and two dozen men spent all night in the forest.”

In the spring of 1979, Avdonin told me, he and several fellow geologists, hoping to locate the remains, obtained permits to conduct scientific research in the area. The ruse worked, and they quickly came across a place marked by planks laid in the earth. “There was nobody else around,” he told me. “We took shovels and we started digging.”

Avdonin spied the first bones—“three skulls, with bullet holes. We took them out of the soil. And we covered the place where we were digging, to leave no traces.”

Avdonin said he kept the skulls while he tried to find someone who could conduct forensic tests on them. After a year without success, he said, “we put the skulls back in the grave, because it was too dangerous to keep them.” Had he and the other men been discovered, “we could have easily been put in prison, or just disappeared.”

The men vowed to keep their findings secret, and they did so for ten years. But in 1990, in the last days of the Soviet regime, Avdonin wrote to Boris Yeltsin, at the time the chairman of the Supreme Council of Russia. While serving as Communist Party boss in Sverdlovsk in 1977, Yeltsin had carried out a Politburo order to destroy the Ipatiev house. (A Russian Orthodox church has recently gone up on the site.) But since then Yeltsin had morphed into a democrat, and Avdonin now felt he could trust him. “I told him where the remains lay,” Avdonin told me. “And I asked him to help me bring them back to history.” Yeltsin wrote back, and the next year, investigators from the Sverdlovsk region’s prosecutor’s office, using Avdonin’s information, exhumed nine skeletons from a single, shallow grave.

The bones had been found. Now it was the job of the scientists to make them speak. The Russian government, and Peter Sarandinaki of the U.S.-based Search Foundation, which promotes forensic study of the Romanov remains, asked pre-eminent forensic experts to help identify the skeletons. They included Peter Gill of the Forensic Science Service in Birmingham, England, Pavel Ivanov of the Genetic Laboratory in Moscow and later Michael Coble of the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory in Rockville, Maryland.

A human cell contains two genomes, or sets of genes: mitochondrial DNA, passed down by the mother, and nuclear DNA, inherited from both parents. Nuclear DNA, unique to each individual, provides the most powerful identification tool. But because only one set of nuclear DNA exists in a cell, it is often difficult to obtain an intact sample, particularly from aged sources. By contrast, mitochondrial DNA has hundreds to thousands of copies per cell; more of these molecules are likely to survive.

In this case, the scientists were fortunate: they succeeded in extracting nuclear DNA from all nine skeletons. They found striking similarities in five of them—enough to conclude that “the bones belonged to one family, and it looked like parents and three kids,” says Evgeny Rogaev, a Russian-born geneticist at the University of Massachusetts, who was brought into the investigation.

The scientists also compared mitochondrial DNA from the female adult skeleton, presumably Alexandra, with that of a living DNA donor: Britain’s Prince Philip, who shared a common maternal ancestor—Queen Victoria—with the czarina. It matched.

In 1994, Ivanov, the Moscow-based scientist, obtained permission from members of the Romanov family to exhume Georgy Romanov, the czar’s younger brother, from his grave in St. Petersburg. (Georgy had died suddenly in 1899, at age 28.) Ivanov found that Georgy’s mitochondrial DNA was consistent with that of the adult male skeletal remains. Both samples also showed evidence of an extremely rare genetic mutation known as heteroplasmy.

The evidence led the forensic experts to one conclusion: the bones were those of Nicholas II, Alexandra and three of their five children. “The DNA testing was clear and convincing,” Coble says.

But not everyone was persuaded. Some insisted that the bodies couldn’t belong to the Romanovs, because there were only five related skeletons, not seven. In Japan, meanwhile, a forensic scientist, Tatsuo Nagai, performed DNA analysis on a handkerchief stained with Nicholas II’s blood after a would-be assassin attacked the czar with a sword in Oda, Japan, in 1890. Nagai and a Russian colleague reported in 1997 that mitochondrial DNA from the bloody handkerchief did not match that from the bones the experts had determined to be Nicholas’. (The results were never published in a peer-reviewed journal and were not replicated; the findings have not gained acceptance.) Compounding the confusion, a forensic scientist at Stanford University obtained a finger bone of Alexandra’s older sister, Elizabeth, who had been shot by Bolsheviks in July 1918 and tossed down a well. The mitochondrial DNA from the finger, he reported, was not consistent with DNA from the skeleton identified as that of Alexandra.

Those findings caused controversy, but scientists working with the Russian government contend that both the bloody handkerchief and the finger had been contaminated with DNA from other sources, throwing off the results. Using this 80-year-old bone as a reference, says Coble, “ignored the entirety of the evidence.”

President Boris Yeltsin and the Russian government agreed with Gill, Ivanov and the other forensic scientists. On July 17, 1998—the 80th anniversary of the killings—the remains that had first been uncovered in 1979 were interred beside other members of the Romanov dynasty in a chapel in St. Petersburg’s state-owned Peter and Paul Cathedral.

Russian Orthodox Church authorities insisted that the remains were not those of the Romanovs. The Russian Orthodox patriarch, Alexei—with the support of several key Romanov descendants—refused to attend the ceremony.

Ever since the Romanov bones came to light, Gribenyuk had yearned to locate the still-unrecovered remains of Maria and Alexei. Gribenyuk suspected that the czar’s daughter and son were buried near the timber-covered grave that held the other Romanovs. In 2007, he put together a team of a half-dozen amateur forensic sleuths and headed for the Old Koptyaki Road. On their third search of the area, on July 29, 2007, they located some 40 bone fragments, buried in watery soil at a depth of about one and a half feet, 230 feet from the other members of the royal family.

Coble, the U.S. Army scientist, analyzed the bone fragments and extracted mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from both specimens. He compared the results with data from the remains attributed to Nicholas, Alexandra and their three daughters.

His analysis showed that mitochondrial DNA from the bone fragments of the unidentified boy and girl was distinctly similar to that from Czarina Alexandra. Further analysis using nuclear DNA—which, again, is inherited from both parents—indicated “it was four trillion times more likely” that the young female was a daughter of Nicholas and Alexandra than that she was unrelated, Coble says. Likewise, it was “80 trillion times more likely” that the boy was a Romanov rather than an unrelated male.

Coble and other scientists conducted an additional genetic test, involving analysis of markers on Y chromosomes—genetic material passed down through the paternal line. They compared the boy’s Y chromosome with those from the remains of Nicholas II as well as a living donor, Andrei Romanov, both of whom were descended from Czar Nicholas I. The testing, says Coble, “anchors Alexei to the czar and a living Romanov relative.”

Finally, Solovyev, the Moscow investigator, remembered that a bloody shirt worn by Nicholas on the day of the assassination attempt in Japan had been given, in the 1930s, to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. The shirt had not been seen for nearly 60 years. It was eventually traced to a storage-room drawer. Because of the age of the blood and the possibility of contamination, “I was absolutely skeptical [of getting a good DNA sample],” says Rogaev, of the University of Massachusetts. “But it worked even better than the bone samples.”

“This was the critical thing,” says Coble. “We now had a sample of the czar’s blood, and we had bone samples from after his death. We had living and post-mortem DNA. And they were a perfect match.”

So far, the church has continued to challenge the authenticity of Maria’s and Alexei’s remains, just as it has refused to accept the identification of their parents’ and siblings’ skeletons. And the Russian leadership—President Dmitri Medvedev and Prime Minister Vladimir Putin—who are acutely sensitive to the power of the Russian Orthodox Church, have yet to authorize burial of the most recently unearthed remains with those of the other Romanovs in St. Petersburg. The bone fragments are stored inside a locked medical refrigerator at the Sverdlovsk Region Forensic Research Bureau in Yekaterinburg.

“The criminal case is closed; the bodies have been identified,” says Tamara Tsitovich, a top investigator at the laboratory. “They should be buried as quickly as possible.”

The Rev. Gennady Belovolov, 52, is a prominent clergyman within the Russian Orthodox Church in St. Petersburg. He grew up in the Caucasus, where he was taught in school that the czar was a weak-willed person who failed to save Russia at the most difficult moment of its history. After the fall of the Communists, Belovolov read Russian and foreign biographies, and “I came to see [the czar] as a man with tremendous morality and charm, and his tragic end could not leave any sane person indifferent,” he says. “The story that happened to him became a symbol of what happened to Russia—the lost chance for greatness.”

Belovolov told me that, despite the scientific evidence, he still believed in Sokolov’s 1918 conclusion that the royal family had been burned to ashes at Ganina Yama. “Seventy years later, new people came, they found the remains of unknown victims in a grave and declared they belonged to the czar. [But the Bolsheviks] executed many in the forest during that time.” As for the bones of Maria and Alexei discovered three years ago by Gribenyuk and his friends, Belovolov said, “there are researchers who show completely different results. The church would be happy with only 100 percent certainty, nothing less.”

The church has another reason to resist the new findings, according to several observers with whom I spoke: resentment of Yeltsin’s role in rehabilitating the czar. “The church hated the idea that someone who was not only a secular leader but also a party functionary stole what they thought was their domain,” says Maria Lipman, a journalist and civil society expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Moscow. “This movement to sanctify the family of the czar—they wanted it to be theirs, and instead Yeltsin stole it.”

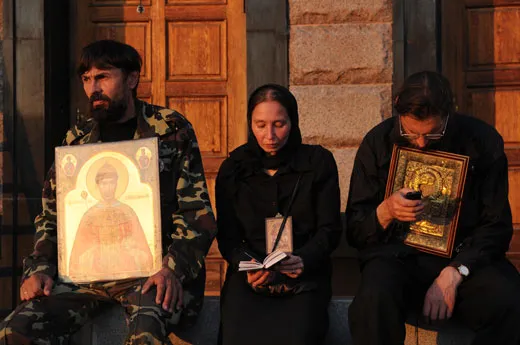

A fascination with the Romanov family’s “martyrdom,” along with what many describe as a spiritual yearning for a strong, paternal leader, have led some Russians to believe that their country’s salvation lies in the return of the monarchy. Each July 17, religious pilgrims retrace the route taken by the bodies of the Romanovs from the Ipatiev house to Ganina Yama; descendants of White Russian exiles have started monarchist societies; the great-grandchildren of Cossacks and Hussars who flourished under imperial rule have agitated for restoration of the Romanov line.

The Russian Imperial Union is a monarchist group founded by White Russian exiles in Paris in 1929. The union’s leader, Georgy Fyodorov, 69, doesn’t buy the forensic conclusions. “Nobody can give you 100 percent assurances that the [ Old Koptyaki Road] bones are those of the emperor,” said Fyodorov, the son of a White Russian Army major. “Nicholas told [his supporters] before he was killed: ‘Don’t look for my body.’ He knew what would happen—it would be destroyed completely.”

In support of their view, Fyodorov and Belovolov both cite the discredited results obtained from the Japanese handkerchief. And they question why the skull attributed to Nicholas bears no mark from the Japanese saber attack. (Forensic experts say that acidic ground conditions could have leached away such a marking.)

Fyodorov, who lives in St. Petersburg, said that Avdonin and his supporters have “political reasons” for pushing their version of events. “They want to put an end to it—‘God bless them, goodbye Romanovs.’ But we don’t want [the issue] swept away. We want the monarchy to return.”

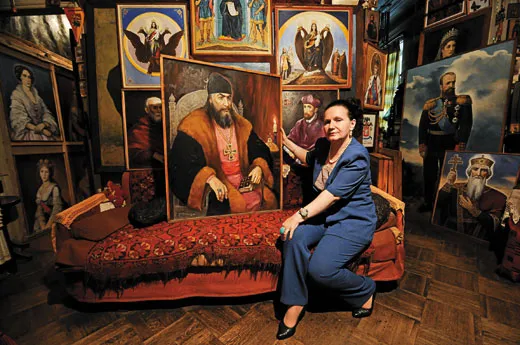

Xenia Vyshpolskaya, a self-employed portraitist specializing in the Romanov czars, is not only pro-monarchy but might be considered pro-fascist as well. On her wall, squeezed in among the Romanovs, are framed photographs of Francisco Franco, Benito Mussolini and Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet. Vyshpolskaya told me that her ambition is “to have a gallery of the world’s right-wing leaders....Each of them, like Nicolay, tried to take care of his people. You can agree or disagree with their methods.”

Such sympathy for fascist strongmen is not unusual among those in Russia who, like Vyshpolskaya, support the return of the monarchy. The Russian Imperial Union’s Fyodorov told me that he was hoping a right-wing general would overthrow the Russian government: “Someone like Franco [should] take power, become a dictator, clean up the mess, and in two or three years restore the monarchy.”

“The monarchy was brutally put to an end, and it was a tragedy for Russia,” says Princess Vera Obolensky, who claims to be a descendant of the 16th-century czar known as Ivan the Terrible. She grew up in Paris and emigrated to St. Petersburg three years ago.

“The monarchy is a romantic idea,” says French historian Mireille Massip, an expert on White Russian exiles. “Democracy is not popular, because democrats turned out to be total losers. Communists aren’t popular. Monarchism is seen as something fresh and fashionable.”

The Russian Orthodox Church has created a memorial to Nicholas and his family in the woods at Ganina Yama. When I visited it with Gribenyuk, we parked next to a row of tour buses and walked through a wooden gate flanked by souvenir kiosks. Tourists and pilgrims browsed through Nicholas pins, postcards and orthodox icons. Perhaps nowhere was the link between the church and the royal family more evident. Religious choral music blared from loudspeakers. Just beyond a large bust of Nicholas, its base inscribed with the words “Saint, Great Martyr and Czar,” footpaths led to a dozen churches of varying sizes scattered through the woods. Each of these impressive structures, constructed of rough-hewn logs and topped by a green-tile roof and golden dome, was dedicated to a different patron saint of the Romanovs. We approached a plank walkway that surrounds a grass-covered pit—the abandoned mine where the Bolshevik death squad first dumped the corpses after the regicide. One worshiper was laying a bouquet of white lilies on the grass. Priests and tour groups led by young acolytes wandered past. “The church has really built this [complex] up,” Gribenyuk observed.

At the same time, the church appears poised to obliterate the sites uncovered by Avdonin and Gribenyuk, a few miles away, where, according to the government and forensic scientists, the Romanov remains were found. Last year, the church tried to acquire the land and announced plans to construct at the site a four-acre cemetery, a church and other structures bearing no connection to the Romanovs.

“It is enough to cover up everything,” said Gribenyuk.

This past spring, he and others filed a legal action to block the project, arguing that it would destroy one of Russia’s most important landmarks. (As we went to press, the court ruled against the church. The decision is likely to be appealed.)“The bodies were buried here 92 years ago,” Gribenyuk said, “and now the church wants to bury the memory of this place again.”

Joshua Hammer, who wrote about Sicily’s Mafia in the October issue, lives in Berlin. Photographer Kate Brooks is Istanbul based.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)