Retracing the Footsteps of China’s Patron Saint of Tourism

Travelers are discovering the Ming dynasty’s own Indiana Jones, an adventurer who dedicated his life to exploring his country’s Shangri-Las

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a6/e8/a6e86478-1148-4a23-8ccf-28c3c3e484f2/apr2015_f06_mingdynasty.jpg)

To conjure the lost world of imperial China, you might resort to the tales of Marco Polo, that famed Venetian interloper and fabulist. But you could find a more intimate view in the lively work of the most revered ancient Chinese travel writer of all, Xu Xiake (pronounced “Syoo Syah-kuh”), hailed by his growing number of modern admirers as, among other things, “imperial China’s Indiana Jones” on account of his death-defying adventures.

Born in 1587, he was an imposing figure, over six feet tall and as sinewy as a warrior monk, with luminous green eyes and an ascetic air. At age 20, the well-to-do young scholar decided to devote his life to his “wanderlust” and “love of the strange,” taking the poetic nom de plume Traveler in the Sunset Clouds. Voraciously curious, he would tackle any mountain peak—“as nimble as an ape and as sturdy as an ox,” one poet said—to experience a sublime view, which would inspire him to rapture. “I cried out in ecstasy,” he wrote of one summit, “and could have danced out of sheer joy and admiration.” A friend described Xu’s character as “Drifting with the Water, Floating in the Wind,” while another called him “half stubborn, half deranged.”

It’s our good fortune that Xu was at large in the golden age of Chinese travel, during the prosperous Ming dynasty (1368-1644), when commerce was booming and transportation was safer and more efficient than ever before. Tourist numbers reached record levels, seemingly in response to a proverb of the time that an educated gent should “read ten thousand books and travel ten thousand li,” referring to the imperial measure of roughly one-third of a mile. Xu’s literary monument would be his travel diary, or youji, which he intended to edit for publication. But he died at age 54, almost certainly of malaria, before he had the chance. Today scholars see that as a boon to history.

Because there is so little casual prose from the period, this unedited version, which runs to 1,100 pages, has unique historical value. “It’s a spontaneous, step-by-step account of his experiences on the road,” says Timothy Brook, a historian who has written several books on the Ming dynasty, most recently Mr. Selden’s Map of China. “His remarkable powers of observation bring the era to life for us in an extraordinarily vivid way.” The pages overflow with sharp details—encounters with camel herders, complaints about inns, comic arguments with recalcitrant porters. The enormous text was hand-copied by relatives and officially published by Xu’s descendants in 1776.

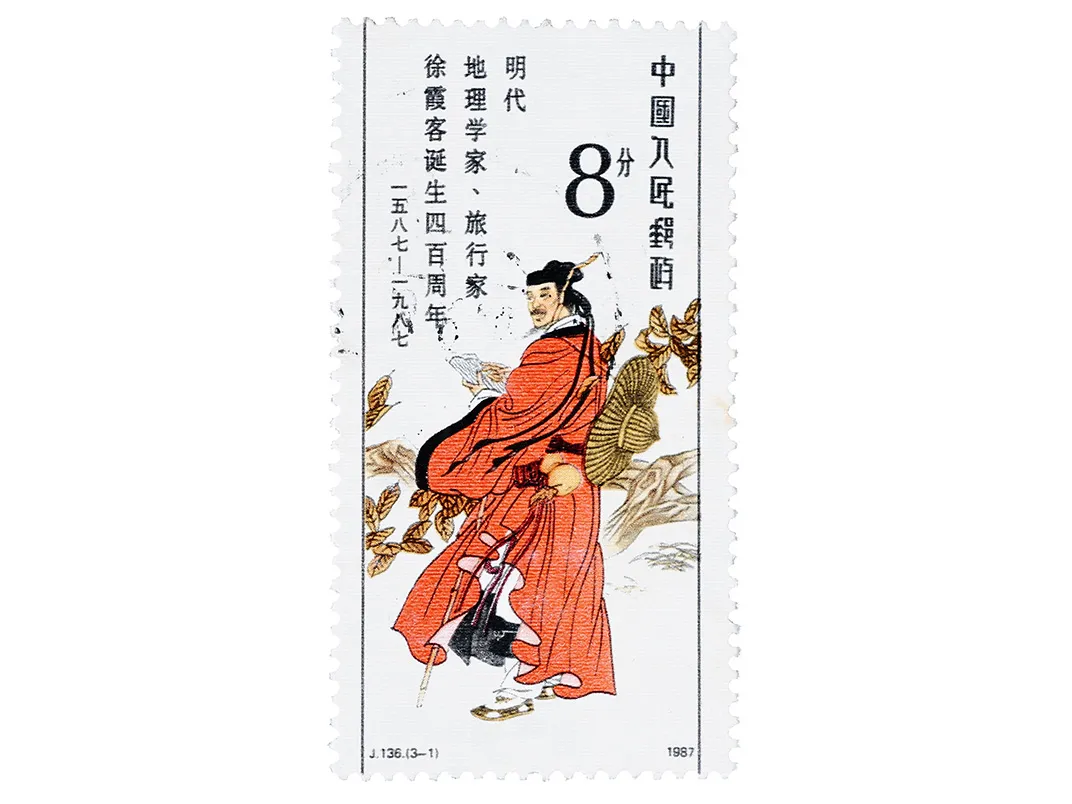

Xu Xiake has long been admired by Chinese intellectuals for his poetic writings and by others for his enviably footloose lifestyle—even Chairman Mao once said, “I wish I could do as Xu Xiake did.” But today, as millions of newly affluent Chinese are starting to travel, Xu is being reborn as a pop-culture celebrity. Beijing has embraced him as the “patron saint” of tourism, giving a gloss of ancient tradition to the lucrative new industry. Postage stamps have been issued in Xu’s honor and statues erected in the towns he visited. His diary has been reissued in annotated editions for academics and graphic novel versions for children, and a biopic has been broadcast on national TV. China’s National Tourism Day is May 19, the date he started his first journey, in 1613. There are now Xu Xiake travel awards and Xu Xiake rock-climbing contests. Most surreal, his ancestral home near Shanghai is now a national monument with a tourism park attached. Walking trails are signposted with images of our hero, like a kung fu film star, swinging down cliffs by rope, crawling through crevices on his stomach and fighting off bandits with his staff. Bill Bryson or Jan Morris or Paul Theroux could only dream of such hero worship.

To me, there was an intriguing irony that a land known for its teeming population and unrelenting industry should embrace a travel writer who was so solitary and poetic. Readers of Xu’s diary are surely struck by the gulf between his romantic ideals and the brash reality of China today, where sites like the Great Wall are jammed with bus tours. “The Chinese government’s entire raison d’être is bigger, faster, more,” says Brook. “It certainly wasn’t Xu Xiake’s. He was in love with nature. He would pause on his journey to watch a stream flowing. He just wanted to contemplate the world.”

Xu Xiake’s last and most ambitious road trip was to Yunnan, which happens to be on the front lines of Chinese tourism today. This scenic province in the foothills of the Himalayas was particularly difficult to reach in Xu’s time and represented a lifelong dream. He set off in the fall of 1636, at age 49, crowing to a friend, “I will make a report on the exotic realms,” and on a four-year journey he explored Yunnan’s snow-capped peaks and tropical valleys, visiting Buddhist monasteries and mingling with extraordinary cultures on the border of Tibet. Today, Yunnan has again become the ideal fantasy destination in China, and for reasons Xu Xiake would actually applaud. Young Chinese who have grown up in the polluted industrial cities are valuing its electric blue skies, pure mountain air and aura of spirituality. On one recent visit to China, I met a hiking guide in her 20s who had escaped the reeking factory zone of Guangzhou and had the zeal of a convert: “For Chinese people, Yunnan is where your dreams can be fulfilled.”

As I hopped a flight in Hong Kong for the Himalayas, I was wary of more than the altitude: In the new China, dreamscapes can vanish overnight. So I decided to follow Xu Xiake’s own travel route to find any vestiges of his classical Yunnan, hoping that the changes over the last 375 years wouldn’t require too many creative leaps of imagination.

In China, any destination that has been “discovered” is affected on a staggering scale. This was obvious when I landed in Lijiang, a legendary town at 8,000 feet in elevation, beneath Jade Dragon Snow Mountain, which for centuries has been the most idyllic entry point to Yunnan. When Xu arrived in 1639, he found it a colorful outpost populated by the proud Naxi people, its streets lined with willows and canals fed by pure alpine springs. This was the very edge of the Chinese empire, where Han settlers from the overpopulated coast mingled with local cultures considered half-barbaric. The monarch, Mu Zeng, invited the traveler to an epic banquet of “remarkable foodstuffs,” including a beloved Himalayan delicacy, yak tongue—although Xu couldn’t quite appreciate the flavor, he complained, because he was already too full and inebriated on rice wine.

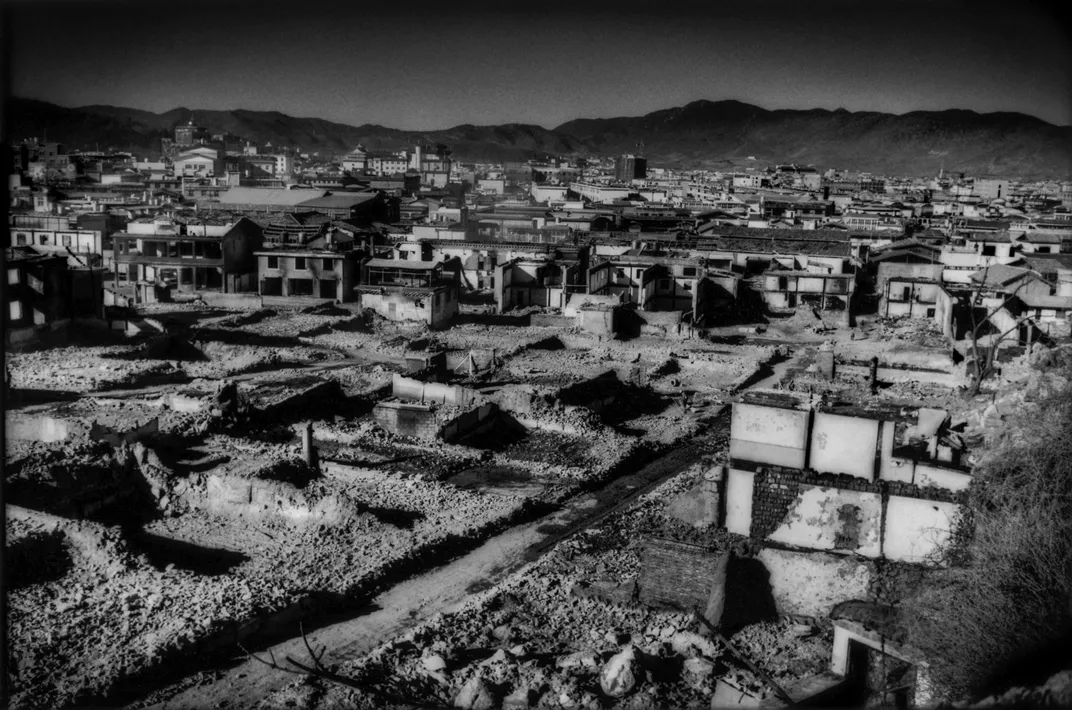

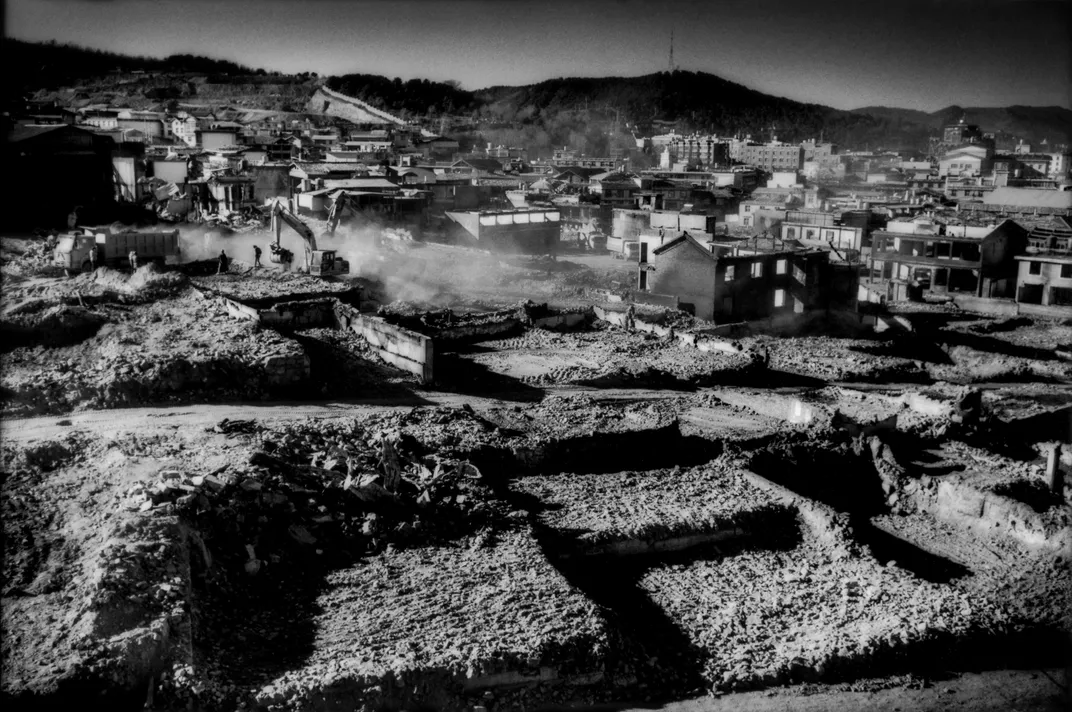

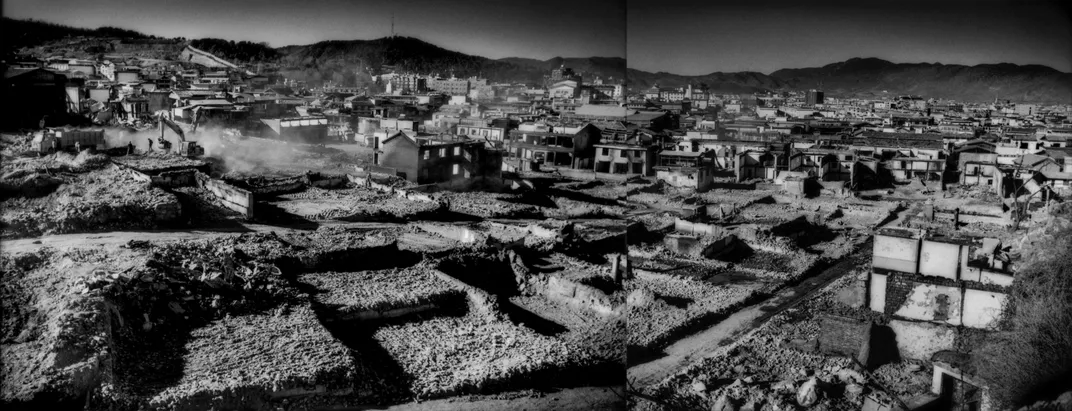

Centuries later, at least the hedonism lives on: Lijiang has reinvented itself as China’s most raucous party town, with an ambience resembling a Shanghai nightclub. Its ancient storefronts have been lovingly restored, but behind the delicate lattice shutters are karaoke bars, where singers compete over loudspeakers, wailing along to Korean pop. The cobblestone alleys are jam-packed with young revelers from every corner of China. Lijiang is a parable of the dangers of success. It was barely known before 1997, when Unesco anointed its historic center as one of China’s first World Heritage sites. Since then, tourism has been promoted without planning or restraint, and a mind-boggling eight million visitors a year now flush through its narrow streets, making Venice seem a model of bucolic calm. To its critics, Lijiang is an example of everything that can go wrong with Chinese tourism. Officials promote economic growth at any cost, they argue, pointing out that the historic part of town has been overrun with cheap souvenir stores while local residents have been driven out. Johnson Chang, a Chinese art curator and expert on traditional culture, argues that the mass tourism model can devastate historic sites as completely as a wrecking ball. “It used to be that government officials would knock down old China because they thought it had no economic value,” he said. “Now they just turn it into a Disney-style theme park.”

It was some comfort to read that even in the Ming dynasty commercialism was a danger. Xu Xiake was annoyed to find that at famous grottoes, extra fees were charged to cross suspension bridges or to use rope ladders. On holy mountains, some visitors hired sedan chairs in order to be carried to the summit, or even “sea horses”—local farm boys who transported tourists on their backs, tied on by cloth strips like swaddled babies. There were package tours: Confucius’ birthplace, Qufu, was a prototype tourist trap, with three grades of tour on offer in the rambling hotel complexes. After a guided climb of nearby Mount Tai, first-class guests were treated to a gourmet meal and exquisite opera, while budget travelers made do with a lute soloist. And red light districts thrived. At one jasmine-scented resort south of Nanjing, powdered courtesans sang seductive songs at their windows, while waves of male customers filed back and forth before them. When a client made an assignation, a spotter would yell out, “Miss X has a guest!” and torch-bearing assistants would lead him inside via a secret doorway, according to one account in Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China. Later, however, “a tinge of desperation” would prevail as hungover men “groped their way through the darkness like ghosts.”

In modern Lijiang, the only way to avoid the chaos is to emerge in the early hours of the morning. The town is eerily silent, and I wandered the maze of alleyways to the Mufu Palace, just as Xu Xiake had done when he met with the Naxi king. For a full hour, it was a haunting experience. I had breathtaking views over the terra-cotta roofs of the old town, looking like a sepia-tinted postcard. Even more evocative are the nearby villages just below the snow line, where houses are crafted from gray stone and Naxi women still carry water barrels on their backs. Here, ancient traditions are still resilient. In Baisha, I met a traditional herbalist named Dr. Ho, who in his 90s plies his trade in a rambling house crammed with glass vials and plants. (His health advice was simple: “I recommend two things. First, stay positive. Second, be careful what you put in your mouth.”)

Dr. Ho suggested I visit Xuan Ke, a classical musician whose passion for the guqin, a zitherlike stringed instrument, traces a direct lineage back to the literati of the Ming period. During the Communist rampages against the arts, Xuan spent 21 years as a prisoner in a tin mine. On his release, he reunited with Naxi musicians who had met in secret to pass on their skills, often rehearsing in silence, using lutes with no strings, drums with no hide and flutes without wind. Now a successful recording artist in his late 80s, he lives like a reclusive rock star in a grand mansion where a half-dozen ferocious Tibetan mastiffs are kept on chains. Thanks to the stubborn Naxi spirit, Xuan told me, classical music has survived in Yunnan better than other parts of China. “Everywhere else, young musicians try to update the original style,” he said. “But we see the value of staying the same.” To prove the point, he invited me to hear his Naxi Orchestra not far from Lijiang’s karaoke strip. During their performance, the 30 or so elderly musicians were forced to compete with the booming rock music from the nearby bars. While surtitles translated the singer’s ethereal lyrics into English—“A lotus on the fairy’s hand dabs dew on a golden tray,” for example—the bass from the karaoke clubs grew so loud that my seat began to shudder. But like the musicians on the Titanic, the Naxi artists didn’t falter a beat, or even acknowledge the din. At least they were free to play.

It wasn’t at first obvious how I would recapture Xu Xiake’s love of nature, even in Yunnan. For example, one of the world’s deepest ravines, Tiger Leaping Gorge, has been marred by a highway carved along its flanks and viewing points clogged by tour buses. But by following the offbeat route recorded in Xu’s diary, I was able to encounter more pristine worlds.

A crowded local bus took me 112 miles south to Dali, a lakeside town beloved in the Ming dynasty for its warm climate, fertile soil and spiritual aura. Now Dali is similarly admired as a Chinese hippie hangout, with funky vegetarian cafés that serve rare mushrooms and edible tree fungi such as spongy “tree ears” and a crisp item charmingly translated as “frog’s skin.” Its embryonic hipster culture has fostered a new environmental awareness. “Yunnan hasn’t been as scarred by China’s development craze over the last 30 years,” said an American expat, Andrew Philhower, as we sat in a sunny craft beer garden that would not have been out of place in Boulder, Colorado. “So now they have a better chance of avoiding past mistakes. People are already aware of what they have to lose.”

And certainly parts of Dali’s landscape remain just as Xu Xiake would have seen them. I climbed one steep trail through the tea terraces into Cangshan National Park, through yawning canyons where autumn leaves fell like flakes of gold dust. Emulating the graffiti poets of old, park officials have dabbed inspiring messages on the trail in red paint: “Enjoy being here!” one exhorted. Another: “Save the memories!” A third, after a tiring incline, seemed more forlorn: “You can see the bright side of everything.”

On his way to the Butterfly Spring, where thousands of fluttering insects still gather every spring in a whirlwind of color, Xu passed a village called Xizhou (Happy Town). I was delighted to discover it is now home to a creative experiment in sustainable tourism, the Linden Centre. In contrast to the glitzy high-rise hotels that sprout in China’s megacities, the 16-room guesthouse is a renovated courtyard mansion, with an ambience more akin to an eco-lodge in Brazil. It’s the brainchild of American expats Brian and Jeanee Linden, who decided to offer travelers a taste of the ancient arts, such as calligraphy, painting and tea ceremonies. “We looked all over China for the right location,” Jeanee recalled, before finding this antique residence, which had survived the revolution with its décor largely intact because it had been a barracks for army officers. Even so, renovations proceeded fitfully. In a Chinese version of A Year in Provence, the difficulties were less with quirky tradesmen than interfering bureaucrats from four different levels of government, who held up work for months at a time.

Today, the Linden Centre is a modern update of the aristocratic refuges Xu stayed in, where provincial literati invited him to enjoy art and music over erudite banter. When it opened in 2008, it was an instant success with foreign travelers starved for historical charm in China. Chinese guests, accustomed to their five-star amenities, were at first shocked to find that, instead of Gucci and Prada stores, the Xizhou village market offered string beans and pig’s feet. But a more open attitude is emerging. “Our Chinese guests are now highly educated. They’ve been to Europe and the U.S. And they want to exchange ideas,” says Jeanee, who estimates that a quarter of the center’s clientele is now local Chinese. “Yunnan is really like a laboratory of tourism. Suddenly, the new generation wants a genuine experience.”

Traveling into the remoter regions of Yunnan is still a challenge. Squeezed into tiny bus seats on bone-jarring cliff highways and bartering for noodles in roadside stalls, I began to realize that few in the Chinese government can have actually read Xu Xiake’s diary. Despite his devotion to travel, he is an ambiguous poster boy for its pleasures, and as his diary attests, he suffered almost every mishap imaginable on his Yunnan journey.

He was robbed three times, contracted mysterious diseases and was lost and swindled. After one hapless mountain guide led him in circles, Xu questioned the whole effort: “I realized this was the most inauspiciously timed of a lifetime’s travels.” On another occasion, while waiting for funds after a theft, he became so broke he sold his clothes to buy food. He once recited poetry in exchange for mushrooms.

Sadly, Xu’s traveling companion, a monk named Jingwen, fell ill with dysentery on the road and died. He was an eccentric character who apparently carried a copy of the Lotus Sutra written in his own blood, but he was devoted to Xu, becoming injured while defending him from a violent robbery. Xu, devastated, decided to bury his friend’s remains at the ostensible goal of the journey, a sacred peak called Jizu Shan, which is now almost entirely forgotten by travelers. I decided to follow his footsteps there, too. (The name means Chicken Foot Mountain, referring to its unique shape, three spurs around a central summit, resembling a fowl’s claw.)

In the Ming dynasty, all mountains were considered the homes of immortal beings and were thought to be riddled with haunted caves where one might find hidden potions of eternal life. But Jizu Shan also boasted a thriving Buddhist community of resident monks, luring pilgrims from as far away as India and Mongolia. Xu lived on the mountain for several months, captivated by its otherworldly beauty while staying in a solitary hut far from the pilgrim hordes whose torches lit up the sky “like the glittering stars.” (“Spending the night of New Year’s Eve deep in the myriad peaks is better than a thousand nights in the world of men.”) Xu even wrote a guidebook to Jizu Shan in verse, citing ten great attractions.

Today, the rare visitor to Chicken Foot Mountain finds an old cable car installed by the local government in a vain attempt to boost tourist numbers. When I arrived, the only other passenger was a pious banker from Beijing. Suddenly, the lack of crowds made Jizu Shan a magical site. My goal was to find Jingwen’s burial site, which Xu Xiake chose because it had the best feng shui on the mountain, but my only directions were from a cheap, not-to-scale map. Setting off into the forest, I passed a broad, carved-out tree where a bodhisattva, or Buddhist holy man, had once lived for 40 years. Inside was an altar and—I was startled to find—a real monk. He told me he had been living in the tree for a decade, and had learned to sleep upright, in the lotus position. He showed me the site of the house where Xu stayed; it had survived until the 1960s, when the Red Guards destroyed it along with many other religious buildings.

He pointed the way to Jingwen’s tomb, and I couldn’t resist asking if he was lonely in his tree. “How can I be?” he smiled. “I have the Buddha for company.”

Half an hour later, I stumbled across the grave along with a marble wall bearing Jingwen’s name. It did indeed have a panoramic view to a slender pagoda on a knife-edge cliff, and I noticed the monk’s spirit had still not been abandoned: a box of incense sticks was hidden in a niche, along with three matches. It seemed appropriate to light an offering. The first match blew out in the wind. So did the second. But the last spluttered to life, sending up a sweet plume.

The site felt like a poignant memorial to Xu Xiake himself. When he buried his friend here in 1638, Xu was uncharacteristically weary of travel. “Now with (my) soul broken at the end of the world,” he mourned, “I can only look alone.” Xu returned to Jizu Shan at the end of his Yunnan expedition, in 1640, but he was exhausted and ill. He had contracted what was probably malaria in the jungle lowlands. The disease became so serious that his royal patron, the Naxi king, provided a sedan chair to carry him home across China, a journey that took roughly six months. But once back in his ancestral residence, the inveterate traveler was unable to settle down. According to a friend, Xu felt indifferent to his family and preferred to lie all day in his bed, “stroking some of his strange rocks.”

One is reminded of Tennyson’s Ulysses: “How dull it is to pause, to make an end / To rust unburnished, not to shine in use!” Xu died in 1641.

Tradition holds in China that before he became ill, Xu Xiake continued his journey from Yunnan north into the Buddhist kingdom of Tibet. The land had always fascinated him, and he had even written an essay about the Dalai Lama. But most historians dismiss the idea. The overwhelming evidence suggests that King Mu Zeng forbade the trip because the road north was filled with bandits, and Xu obeyed.

Today, the border of Yunnan and Tibet is a final frontier of Chinese travel, and it seemed to offer a glimpse of how the future would unfold. In 2001, the county—including the only town, Dukezong—sold out by renaming itself Shangri-La and claiming to be the inspiration for the 1933 novel and 1937 Frank Capra film, Lost Horizon, about a magical Himalayan paradise. The name change has been a huge public-relations success. And yet, the Tibetan culture was said to be thriving in the shadows. So I hitched a ride there with a French chef named Alexandre, in a yellow jeep with no windows. For the five-hour journey, I huddled under rugs wearing a fur hat to protect against the freezing wind and sunglasses to block the blinding light. After all the crowded bus trips I’d taken, being in the open air was exhilarating; I felt acutely alive, much as Jack Kerouac had said of his ride in the back of a pickup truck speeding through the Rockies.

Jagged mountain ranges eventually closed around us like jaws. Tibetan houses huddled together in enclaves as if for warmth. Women trudged by with sun-beaten faces, their babies in woolen slings. The real Shangri-La was no paradise, with trucks rumbling down the streets carrying construction materials for the next hotel project. Alexandre pulled up before the ornate wooden structures of the old town, where a smoky restaurant was filled with families huddled over noodle bowls. The specialty was a hot pot topped with slices of yak meat, the lean, tasty flesh in a hearty broth fortifying me for the thin air at 9,800 feet.

A few hours later, in the valley of Ringha, one of the holiest places for Buddhists in the Himalayas, the remote Banyan Tree lodge offers accommodation in sepulchral Tibetan houses that also happen to be appointed with mini-bars and down comforters. On the bottom floor, where farm animals were once stabled, wooden tubs bring relief with aromatic Yunnanese bath salts. And yet, past and present converged easily. When I went for a stroll, pigs meandered by and farmers repairing a roof offered me the local hot tea made of yak milk, salt and butter.

Standing on the steps of the village temple, I raised a cup to Xu Xiake. For a moment, it seemed possible that culturally sensitive tourism could help preserve Yunnan. But after I got back to New York, I learned that a fire had razed much of Shangri-La’s ancient Tibetan town. Someone had forgotten to turn off the heater in a guesthouse. Local authorities, despite their lust for development, had not provided working fire hydrants and the wooden architecture burned like tinder—an irreplaceable loss.

Xu Xiake championed the educational value of travel, and its liberating potential. “A great man should in the morning be at the blue sea, and in the evening at Mount Cangwu,” he wrote. “Why should I restrict myself to one corner of the world?”

But China, of course, is no longer the playground of just one man.

Related Reads

Xu Xiake (1586-1641): The Art of Travel Writing

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)