Photos Capture India’s Ancient, Vanishing Stepwells

These intricate architectural marvels are in danger of disappearing

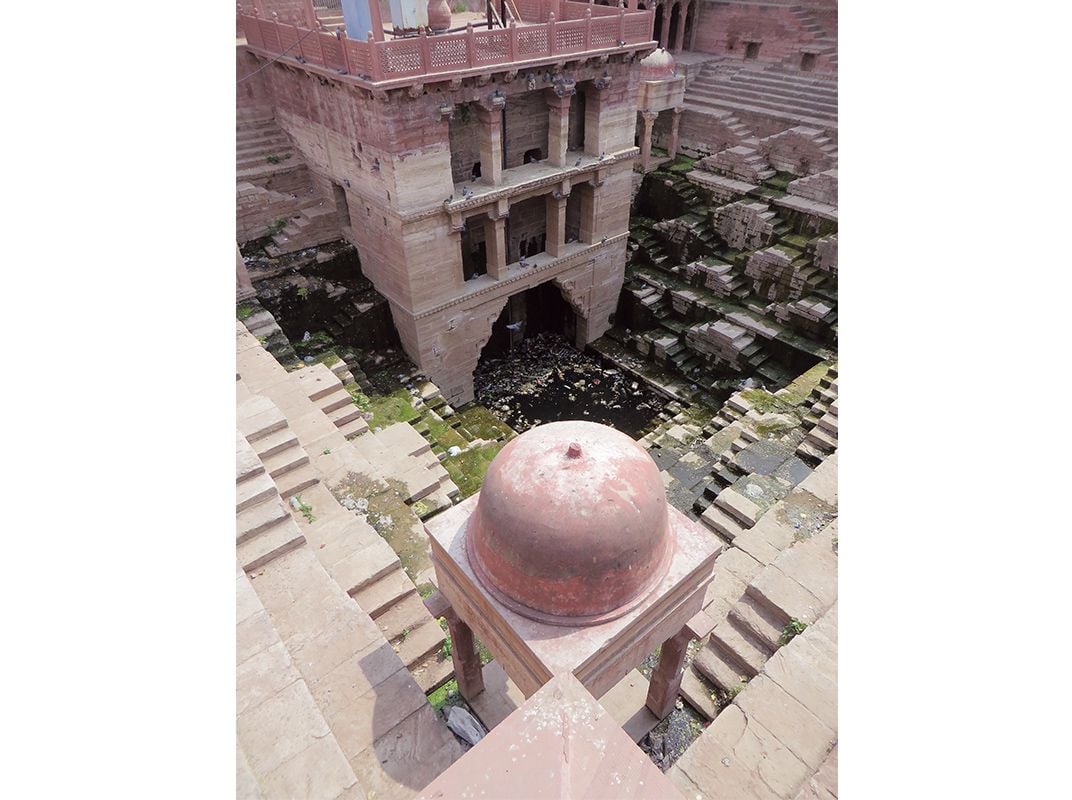

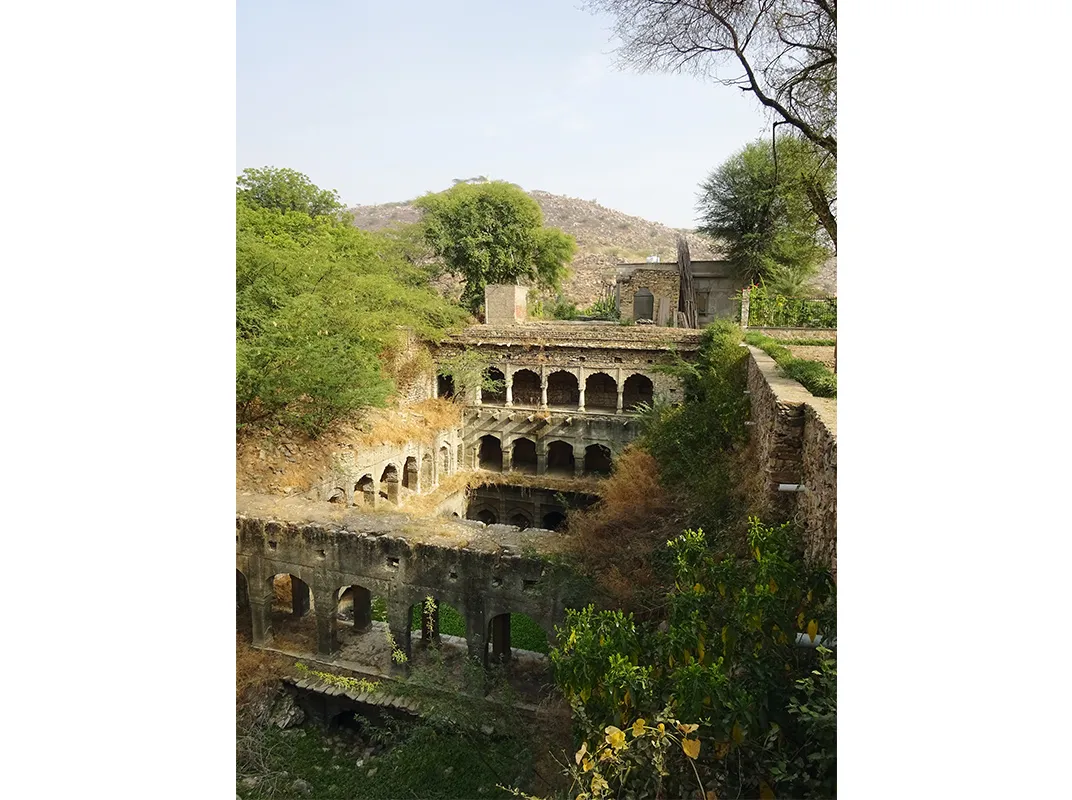

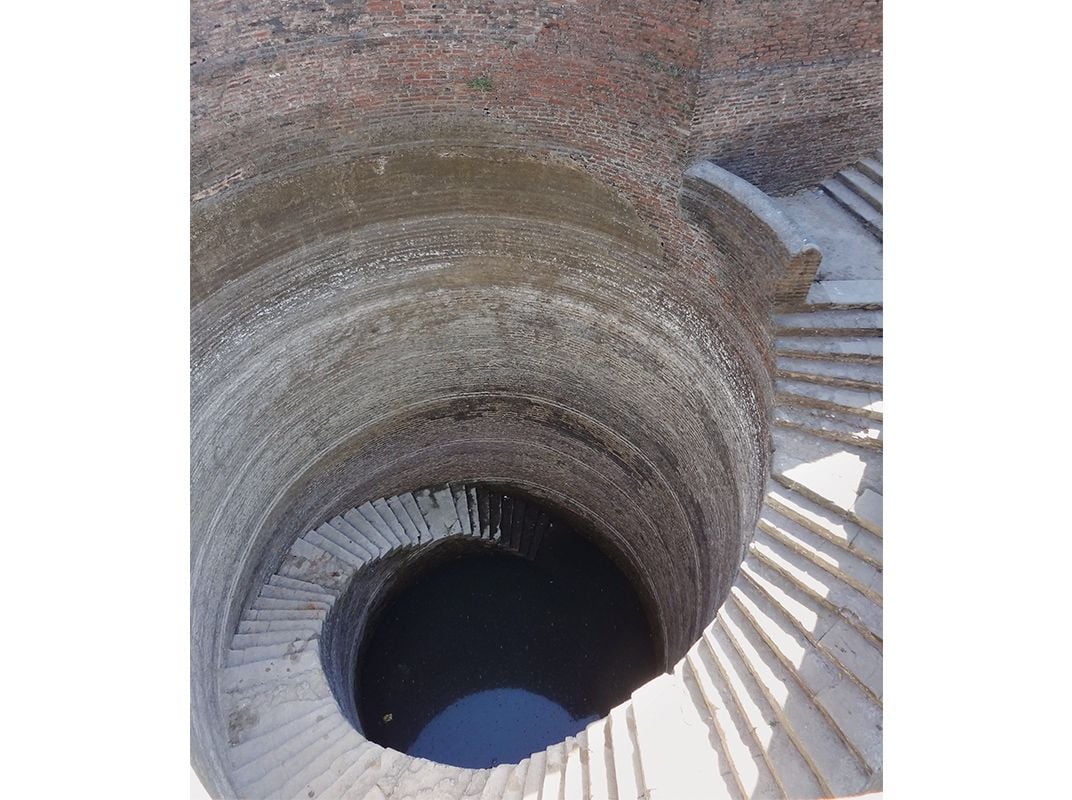

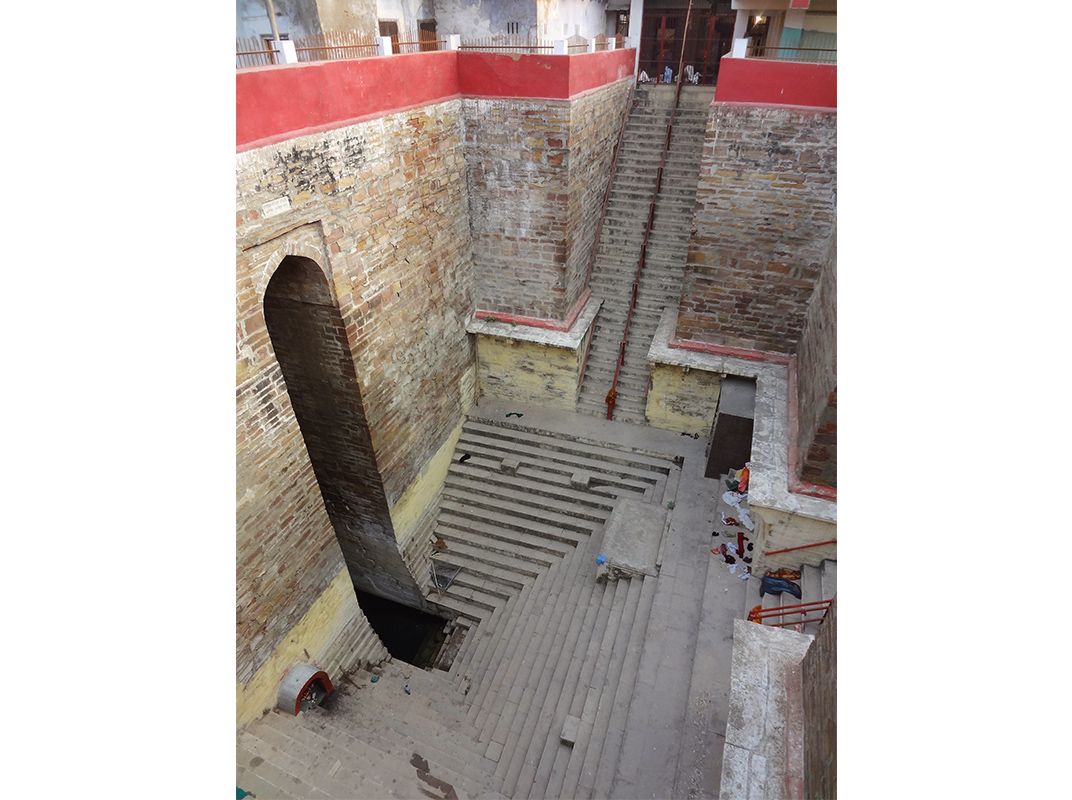

It is easy to miss the vast, ancient stepwells of India even if you are standing directly in front of one. These structures are sunken into the Earth with stairways that spiral or zigzag as far as nine stories down into the cool, dark depths where a pool of water lies. Once an important part of daily life in India, modern wells have replaced them. Walls, vegetation and neighboring buildings have grown up to hide them. Victoria Lautman, author of The Vanishing Stepwells of India, spent years searching them out.

Lautman fell in love with stepwells on her first trip to India.

“My driver took me to this place and let me out of the car in a dusty kind of dirt place and said, 'walk to that wall,'” Lautman recalled. “And I did. It was just a very nondescript low, cement wall and when I looked over it, it was a shocking experience. The ground fell away into what looked like a man-made chasm. And that was it.

"But what was shocking about it," Latman continued, "was that I couldn't recall another experience of looking down into architecture into such a complex man-made experience. It was really transgressive and bizarre. That was the first experience.”

On subsequent trips to India, Lautman sought out stepwells and documented them through photographs and research.

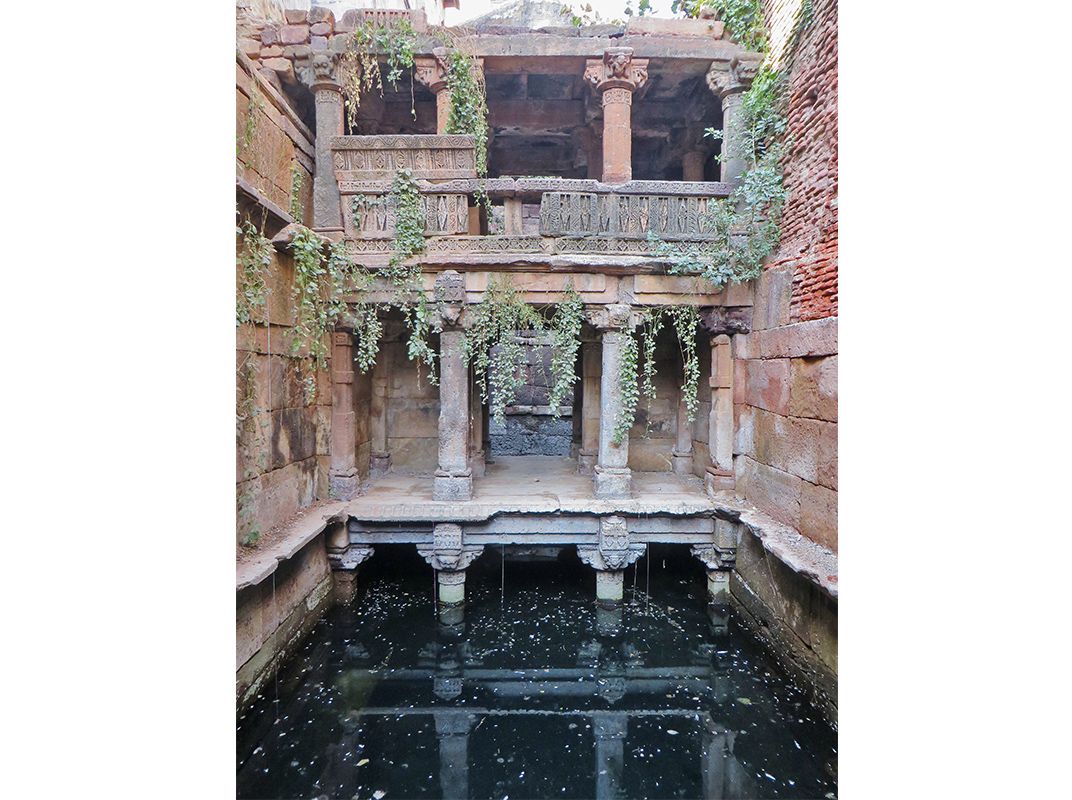

People began constructing stepwells in western India in around 650 AD. They were intended primarily as a source of clean water but also served as gathering places, temples and refuges from the heat. They could be as simple as a spiraling staircase down to a round pool of water in the center, or a busy maze of stairs and columns with the complexity of a sketch by M.C. Escher.

While Hindu in origin, the value of stepwells was grasped by Muslim rulers of the Mughal empire beginning in the early 1500's. Some Hindu religious inscriptions where defaced, but they allowed construction to continue and even built their own wherever they went.

When the British occupied India (succeeding the Mughals) they considered stepwells unsanitary and set about creating new sources of water. Drilled and bored wells became common, along with pumps and pipes that made stepwells obsolete. The vast majority of Indian stepwells fell into disuse. The last one was built in 1903.

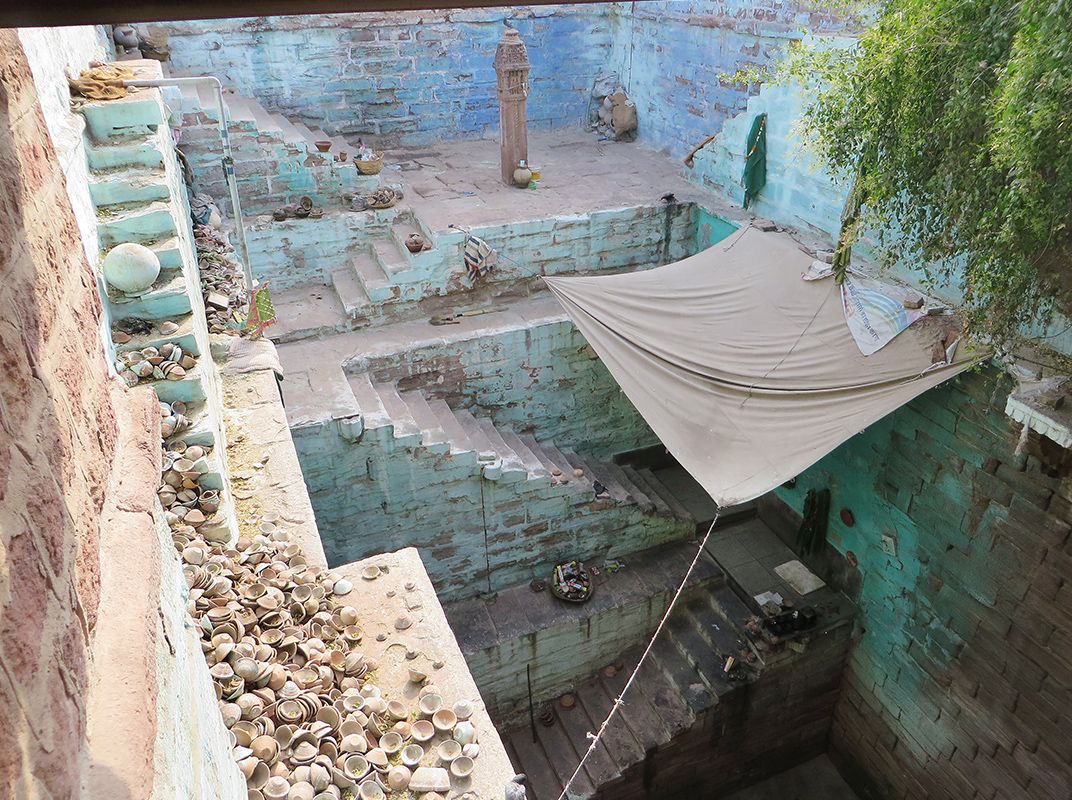

In areas without consistent, coordinated trash removal, many disused stepwells became handy pits into which garbage was (and still is) thrown. Some have been claimed by wasps, rats, snakes, turtles, fish and mongooses.

“[From the photos,] you can't tell how decrepit and rundown and remote and dangerous a lot of these stepwells are,” Lautman says. “I was going into these things by myself and pushing myself to slide down on my butt down a thousand years of garbage, asking myself, 'why are you doing this?' [...] This is not for the faint of heart. Anyone who is afraid of heights or bugs or snakes or just the incredible filth, anybody who doesn't like any of that is going to have a hard time.”

This is architecture that is both ubiquitous and invisible. There are hundreds – perhaps over a thousand – stepwells in India and Pakistan. But Lautman often found that people who lived mere blocks away from a stepwell had no idea that it existed. She has helpfully included GPS coordinates for every well described in her book. (An online, collaborative atlas can also be found here.) A few stepwells, including Rani-ki-Vav (the Queen’s Stepwell) at Patan, Gujarat, have been well-preserved and are known tourist destinations, but most are obscure and difficult for travelers to find.

Lautman has been a journalist for over 25 years, with a focus on arts and culture. She received an M.A. in art history and worked at the Smithsonian Institution’s Hirshhorn Museum before beginning her career in journalism.

While the book is filled with color photographs on nearly every page, Lautman is not a professional photographer. “These photos were all taken with this idiot[-proof] point-and-shoot camera I got at Best Buy,” she says.

During five years of regular travel to India, None of the photographs in this book have been staged. Lautman captures the stepwells as they truly are – often littered with trash and choked with vines.

“To me, the thing that's very compelling about them is that in spite of their condition, the beauty and the power of these things comes through,” says Lautman. “It's important for me to present them in this condition because I feel that if you raise awareness then more people will come and see them. Hopefully more villages will take care of them and respect them.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JacksonLanders.jpg)