A Visit to Robben Island, the Brutal Prison that Held Mandela, Is Haunting and Inspiring

To visit the brutal prison that held Mandela is haunting, yet inspiring

The busload of tourists on Robben Island grew quiet as Yasien Mohamed, our 63-year-old guide, gestured to a bleak limestone quarry on the side of the road. It was here, he said, that Nelson Mandela toiled virtually every day for 13 years, digging up rock, some of which paved the road we were driving on. The sun was so relentless, the quarry so bright and dusty, that Mandela was stricken with “snow blindness” that damaged his eyes.

Nevertheless, Mandela and other heroes of South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement, such as Govan Mbeki and Walter Sisulu, used their time in this quarry to teach each other literature, philosophy and political theory, among other things. “This campus may not look like the fancy university campuses you have in America,” Mohamed said, “but this limestone quarry was one of the great universities of the world.”

Robben Island, a desolate outcropping five miles offshore, is a testament to courage and fortitude in the face of brutality, a must-see for any visitor to South Africa. Tours leave Cape Town four times a day, and the trip includes a bus tour of the island and a visit to the prison.

The island was first used as a political prison in the mid-1600s; Dutch settlers sent slaves, convicts and indigenous Khoikhoi people who refused to bend to colonial rule. In 1846 the island was turned into a leper colony. From 1961 to 1991, a maximum-security prison here held enemies of apartheid. In 1997, three years after apartheid fell, the prison was turned into the Robben Island Museum.

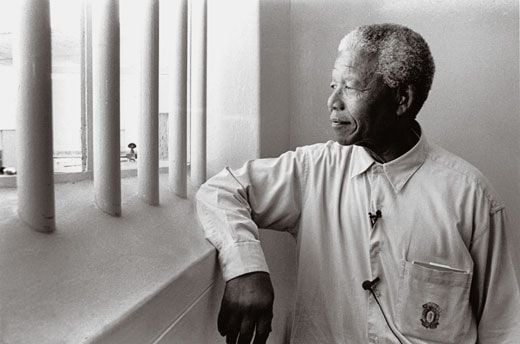

The most powerful part of the tour is a visit to Mandela’s cell, a 7-by-9-foot room where a bulb burned day and night over his head for the 18 years he was jailed here, beginning in 1964. As Mandela recalled in Long Walk to Freedom, “I could walk the length of my cell in three paces. When I lay down, I could feel the wall with my feet and my head grazed the concrete at the other side.”

Many guides are themselves former prisoners, and they speak openly about their lives inside one of the world’s most notorious gulags. Our prison guide, named Zozo, said he arrived on the island in 1977 and underwent severe beatings, hunger and solitary confinement before he was released in 1982. As Zozo stood in the room he once shared with other inmates, he recalled a vital lesson: “Our leader, Nelson Mandela, taught us not to take revenge on our enemies. And because of this today we are free, free, free.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.