Is Europe Returning to Pre Cold War Divisions?

Author Robert D. Kaplan notes the beginnings of a complex map, caused by Russian revisionism, the refugee crisis and a structural economic crisis in the EU

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/45/04459926-e4f5-40e5-be7a-f4d64a68a253/sqj_1604_danube_qa_01-wr-v1.jpg)

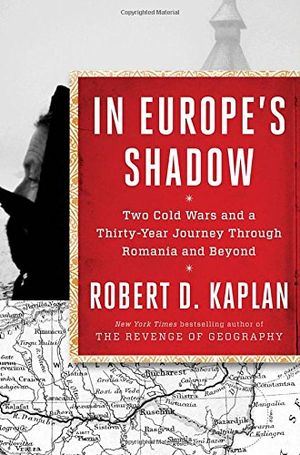

Robert D. Kaplan was a 21-year-old college graduate when he first traveled to Romania in 1973 at the height of the communist era. The country under dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu was dark, depressing, and dangerous. But the journey kindled a lifetime passion for a little-known country in the heart of central Europe. His new book, In Europe’s Shadow: Two Cold Wars and a Thirty-Year Journey Through Romania, weaves together the story of this first journey with subsequent travels to the region, cross-stitched with fascinating excursions down the byways of central European history, literature, and culture.

Speaking from his office in Washington, D.C., Kaplan explains why the Danube is the pre-eminent European river, why Russian president Vladimir Putin has his eyes on the waterway, and how the map of Europe is becoming medieval again.

The Danube carves a watery path across central Europe from the Black Forest to the Black Sea. How important has it been to the history and identity of the region?

One can argue that the Danube is the great river of Europe, more so than the Rhine or the Elbe. It starts in the heart of central Europe but ends in the Black Sea, on the border of the Russian steppe. It’s like an ideogram for greater central Europe. It was the umbilical cord for the Habsburg Empire, which to me is the ultimate, great European empire, and part of the European balance-of-power system that both resulted in wars and produced peace and stability.

Your own particular stamping ground is Romania. Has the Danube shaped that country’s history and culture?

Very much so. The Danube flows through what is today the former Yugoslavia. It defines much of Romania’s southern border, then takes a dramatic almost right angle to go north, before turning east and flowing into the Black Sea. That right angle hook separates a region of Romania called Dobruja from the rest of [the country]. If you go to Giurgiu, a small Romanian city on the Danube, an hour’s drive south of Bucharest, you suddenly see the Danube, very wide, with lots of sea traffic. The river is very much alive with commerce today.

The Danube-Black Sea Canal is today an important part of Europe’s internal waterways. It has a very dark history, doesn’t it?

Yes, it does. And I witnessed it first hand. During the Communist regime under both Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, in the early 1950s and 1960s, and the Ceauşescu regime, from the mid-1960s to the end of the 1980s, it was part of a prison labor system, where men went to work until they died. On my first reporting trip to Romania in 1981, I took a train from Bucharest to Cernavodă, in the Dobruja region, near the Danube, and watched construction on the canal. It was winter. There were scantily dressed workers lining up after a day’s work for the barest rations. It was a horrible scene, which I remember in grainy black and white.

You recently wrote, “As the EU continues to fragment … the continent’s map is becoming medieval again.” Explain what you mean by that.

If you look at the map of Europe in the medieval or early modern period, before the Industrial Revolution, what you see is a mishmash of states and mini-states: Greater this, Lower that, and all the minor German states. It’s a map of dizzying incoherence, which reflected a Europe in conflict. During the Cold War, it was a very simple map. You had two blocs, West and East.

In the post-Cold War period, up until about six years ago, there was this ideal of a super-European state stretching from Iberia to the Black Sea, united by free, open borders and a common currency. But now we see the beginnings of a more complex map caused by Russian revisionism, the refugee crisis, and the structural economic crisis in the EU—all of which harkens back to the medieval and early modern period.

I take it from the title that you think we are in a new Cold War. How does the Danube feature in Putin’s territorial ambitions?

Since the Ukraine crisis began in December 2014, a number of political commentators have dubbed it a second Cold War between the West and what is now Russia. So I used that subtitle for the book.

The Danube figures in this way: we all know about the northern front, the Baltic states and Poland and the Russian threat to that. But remember that Romania, combined with Romanian-speaking Moldova, has a longer border with Ukraine than even Poland has. And traditionally the Kremlin has had an imperial strategy to use the greater Danube area as a jumping-off point for influencing the eastern Mediterranean and the Greek archipelago.

We can’t let you go without telling us what your favorite spot on the Danube is, Robert.

[Laughs] Very good question. My answer is Budapest at night, when I’m looking out from Castle Hill over the various bridges that are strung with lights. I think the combination of water and light over the Danube at night in Budapest rivals that of Paris.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.