Rome’s Very Short Street With a Long, Magnificent History

Taste the food life on the Via Margutta, once home to Fellini and since 1953, the scene of Americans’ sweetest Roman Holiday

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/47/14473ca7-14e4-403c-8b1c-8b6ff26186d8/apr2015_i16_rome.jpg)

Editors' Note, April 9, 2015: This story originally featured a photo that inadvertently included spray-painted graffiti of a swastika tucked behind a planter in a street scene. Our editorial staff was not aware of the offensive graffiti before publication—if we had seen it, we certainly would not have published the photograph. Indeed, the graffiti is disturbing evidence of the current climate in Europe and a reminder that symbols of hate can crop up even on one of the world's most picturesque streets.

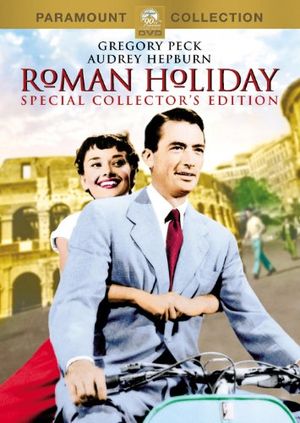

I probably saw the Via Margutta for the first time in 1965. I would have been 7 or 8 years old. I saw it on television. I was an unformed American boy in a formless American suburb and I saw Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn in the back of a cab on their way to Via Margutta, 51. I was watching Roman Holiday on the afternoon movie.

Rome to me in second grade was a daydream, an act of imagination, a confusion of clichés, of Peck and Hepburn and that apartment on the Margutta; it was the Colosseum, the Trevi Fountain, marble and granite, ball gowns and bone-white stone, cypress and staircases and olive trees, an impossible history of gladiators and Caesars and Hollywood, scooters and the Spanish Steps, the Vatican and Castle Sant’Angelo, a hot bright sun and unrequited love. It still is.

In the 50 years since, having finally arrived in Rome, having walked Via Margutta a dozen times, I’ve fallen more widely and deeply in love with it, with its warmth and disorder and mystery, with its fictions and its truths, with the romance of its chaos and decay, with its citizens and its sadness, with its monumentality and indifference to worry, its films and its comic politics and its joyful failures. A city is what it does to you, and Rome defies any attempt by the tourist to describe it—while insisting in every moment that it be described.

Via Margutta is a short street with a long history, three blocks going back 2,000 years. What likely began as an open sewer for the villas and palaces that have come and gone on the Pincian Hill above it is now the most charming little street in Rome. The name likely comes from a sarcasm, an eye-rolling Latin euphemism—“sea drop”—for the foaming pool where the cloacal stream poured down from the backhouses of Rome’s elite. The original buildings were probably stables.

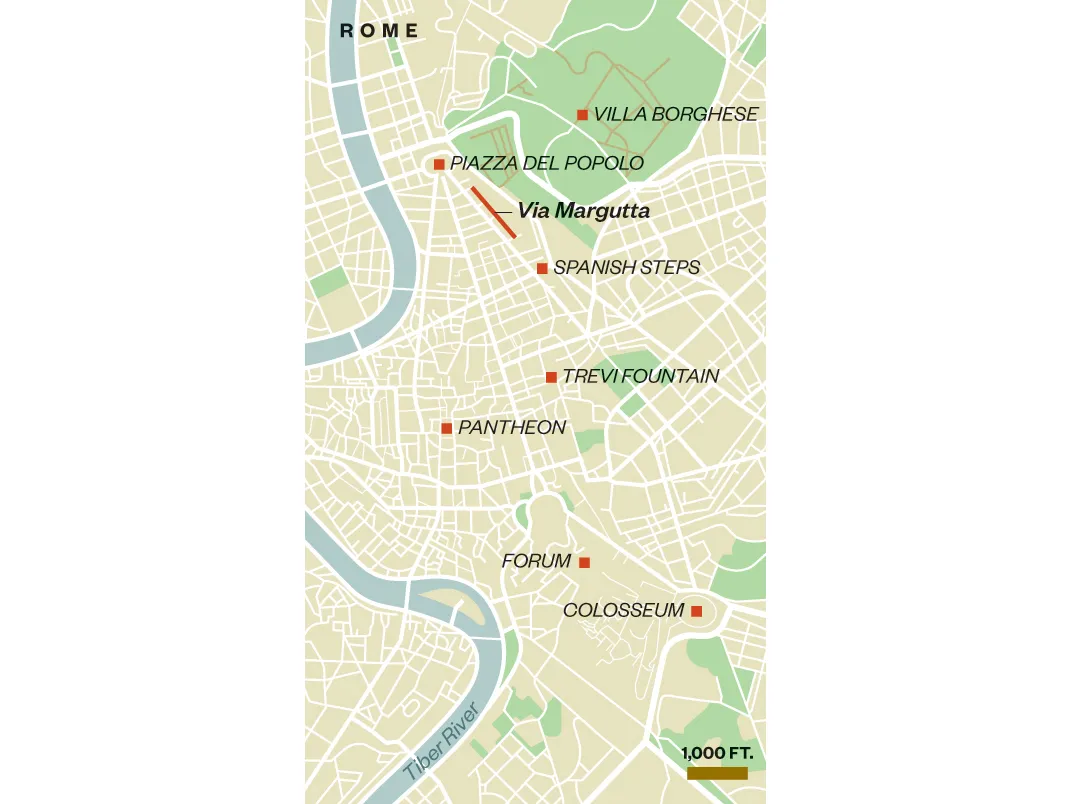

Now it’s an oasis of quiet set between the teeming Piazza di Spagna and the Piazza del Popolo, in the tourist center of the city below the parks and gardens of the Villa Borghese, the Piazza Bucarest and the Viale di Villa Medici. Mostly residential, lined with vining ivy and ocher stucco, cobblestones and window boxes, art galleries and artists’ studios, it is one of the most beautiful streets anywhere.

Maybe that’s why filmmakers dote on it so.

Roman Holiday is a love letter to love, and to Rome and to Hepburn and Peck. It launched America’s postwar tourist business to Italy, and that courtyard apartment is so charming and famous that film buffs from all over the world seek it even today, more than 60 years later. But it’s easy to miss, and when you find it, the door is almost always closed and locked. If you don’t know the movie, the premise was simple: Joe Bradley, played by Gregory Peck, is an American newspaperman scheming for a story and candid photos of runaway princess Audrey Hepburn. They fall in love and he doesn’t get the scoop.

A few years later Federico Fellini personified a variation of that tabloid cynicism in the character Paparazzo in his own film La Dolce Vita, which is the opposite of a love story.

Fellini lived at Via Margutta, 110. For decades he and his wife, actress Giulietta Masina, were fixtures in that colorful street. The marker is still at their apartment door. And the truth is, this, more than anything, accounts for my interest in their corner of Rome. I’ve been an avid fan for many years.

When not recreating the Via Veneto on Stage 5 at Cinecittà, or filming in the park across the Via Tuscolana from the studio, Fellini shot often in his own neighborhood. Once you know the streets around his home, you begin to recognize them in his movies. And in others. The maestro often drank his espresso around the corner at Bar Canova on the Piazza del Popolo by the twinned churches of Santa Maria—near the same spot he used in Roma and La Dolce Vita; and at which Woody Allen later filmed the scene where the newlywed wife loses her phone in To Rome With Love, his love letter to Roman love letters.

Masina and Fellini are gone now, but if you know where to look, and book the right hotel, you can still see the awnings and the shutters and the ornamental fruit trees on what used to be their terrace.

Theirs is the best-known house on the street.

But over the years Via Margutta has been a home to every kind of artist and craftsman, painter and sculptor, composer and poet. By the Middle Ages, it had become a lane of blacksmiths and carpenters and stonecutters. By the 18th and 19th centuries, painters were arriving here in earnest and the street was remade yet again.

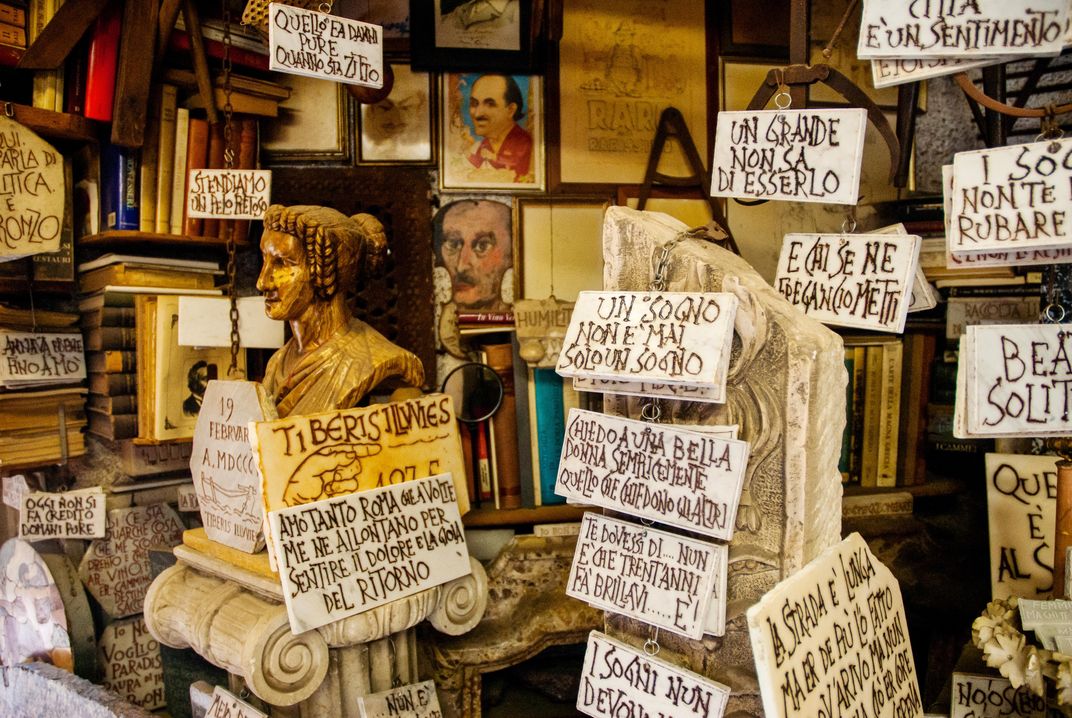

A few doors up is the Goffi Carboni Antiquariato, a gallery and antiques shop with a half century in the street. Among the porcelains and landscapes, Giovanni Carboni will tell you that by the mid-1800s, painters came here from across Europe. Via Margutta was its own school of painting. “Fortuny, for example, came from Spain. Around 1858 he came to Rome to study Italian painting. It was an important school; this was the street of the painters.”

The famous fountain at the far end of the street, the Fontana delle Arti, is capped by a carving of a bucket filled with artists’ brushes. To this day, there’s an annual painters’ festival on the street.

Debussy, Liszt, Puccini and Wagner are all said to have lived on the Via Margutta. Stravinsky, too, who came here with his friend Pablo Picasso. Now oligarchs and well-heeled tourists do their drinking in the Stravinsky bar around the corner at the super-luxe Hotel de Russie, where the Picasso Suite rents for $3,200 a night. Cy Twombly and Salvatore Scarpitta, two of America’s most important postwar modernists, both had studios here. Truman Capote lived at number 33 while writing director John Huston’s Beat the Devil—in the same year William Wyler released Roman Holiday.

I asked another movie buff in an email not long ago what he thought of Roman Holiday, and he wrote back, “I love the film—its romance, its fairy-tale quality, the style it was made in, its great cast and director. I think it’s a beautiful movie and I always loved it. I wanted to be a character in that film.” The movie buff is director Francis Ford Coppola. I also asked him if he knew the Via Margutta. “Sure, the street of the painters,” he wrote back. “Charming.”

Woody Allen wound up on the Margutta mostly by chance, or at least by the design of his production team. “I didn’t know Rome very well. It was really the art director who found all the beautiful locations that we had.” Martin Scorsese’s first film—storyboarded when he was 11—was to be set here, too. Instead, he shot Gangs of New York at Cinecittà studios 50 years later. Antonioni, Visconti, Bertolucci, Fellini, Coppola, Scorsese—it all begins in 1945 with Roberto Rossellini. As Jean-Luc Godard once said, “All roads lead to ‘Rome, Open City.’” So every director from de Sica to Sorrentino has been through here with a camera.

Only four or five or six stories on each side, in every shade of earth, of terra cotta, from one end to the other the only thing I’ve seen of similar scale to rival the Via Margutta are the lesser red rock slot canyons and arroyos of Zion National Park. The warmth off the stone, the sandpaper feel of it under your fingertips, the narrow perfection of light and proportion and sky. Azzurro. Rosso. Celeste. The quiet. Early and late, without shoppers and tourists, improbably, it has that same quality of solitude, too.

Via Margutta is a handy antidote to the crush in the Sistine Chapel and at St. Peter’s and the crowds at the Pantheon and the Forum and the Hippodrome and across the Capitoline. On its worst tourist days, Rome can feel like a wedding cake dropped on an anthill.

Being here can be stressful. It is the condition of most Americans, indeed most Westerners, to feel lately overworked and overscheduled. Our tense dissatisfaction is the near constant state not only of the modern citizen-consumer, but of modernity itself. We wear it in our expression and our step, and if you look up from your phone long enough to glimpse yourself in a plate glass window on the Via del Corso your first day in Rome, you’ll see what I mean.

Then ride the subway, that living catacomb of beggars and the old women rattling their cups of folded newspaper, the homeless sleeping on the platforms; read about the riots, the joblessness, the poverty. Rome is every magnificence and all our squalor.

Yet I find Rome soothing, relaxing, not in spite of these truths, but because of them. Rome insists on my humanity, prompts me to say that while everything changes nothing changes, and that what we know of human nature today is what we knew of human nature 2,000 years ago. It does away with my worries and my ambitions, because you and I are part of a continuum of vanity and appetite moving endlessly back and forward into nothingness.

For all its luminous past, Rome is a city of the unending present. Understanding its magic, its balm to disappointment, is much less important than experiencing it. Its promise of connection, of continuity. Fellow feeling. As if I’ve already lived through everything.

It’s always like coming home.

This is the Eternal City not only for its literal persistence, but because in the right light, on the right street, on the right day, stepping into the long parade of its past, it can make me feel immortal. How slowly time moves, how rarely does my own reality intrude. In a city of the infinite present it is possible at last to forget everything—or remember it. Maybe that’s why everyone’s here. That, and the sunsets.

A city is the stories you tell about it. Love. Passion. Beauty. Memory. Too much to describe, too much to take in. Too much to eat, too much to drink. Too much everything. Rome is hard on its poets. In fact Keats died right around the corner, in that house at the foot of the Spanish Steps.

At this end of the Margutta in late afternoon, you’ll recognize the Osteria Margutta by its antique blue window frames, by the smell of fresh bread and of garlic in oil, and from a sequence in that Woody Allen movie. Alison Pill and Flavio Parenti play a scene here at an outdoor table. (You’ll never go wrong with the carbonara.) There’s another scene with Alec Baldwin, just there, sitting a few hundred feet away. The movie is harmless, a postcard about a postcard from postcard Rome.

But Paolo Sorrentino’s 2013 masterpiece, La Grande Bellezza, the great beauty, extends the Rome staked out by La Dolce Vita. It is very much about longing, loss and mourning a place even as you walk through it, mourning yourself and your past and your future, letting go of ambition and vanity. It is the most stunning movie set in Rome in years. They shot a scene with Toni Servillo right around the corner.

What is it about Rome that so many directors across the decades love? Not only the scenery, but the fraternity, and the competition. According to Coppola, “That so many of those absolutely great Italian directors—more than you can count on all your fingers and toes—all worked there.”

Out front, in the shops and restaurants on the Via del Babuino—baboon street—is where the real tourist action is, and where the spending happens. Back here it’s all morning glories and wisteria and shell limestone door frames. The painted ceilings of the improbably small hotels. I walk it whenever I can, in rain or shade or under the fat lemon sun. Always the feel of a movie set, of dress extras in perfect suits walking perfect dogs. Singles. Couples. Lost families with too much luggage. The bored. The resigned. The metronome of high heels on the cobbles. The overheard dialogue, the spats and reconciliations, all those musical vowels, the sweet nothings and the smell of gardenia and sandalwood corkscrewing out of the boutiques. The sound of water in that fountain.

Up the block, at 61A, there’s been an overnight smash-and-grab robbery. The candy-cane police tape is incongruous across the front of the GB-Enigma jewelry store, a super-luxury outpost owned by a scion of the Bulgari family. Thieves have taken a sledgehammer to every display window and methodically emptied them. For now, you can still see the damage in the Google street-view images of the store. It is a rare thing when reality gets even a toehold here. Via Margutta is a fantasy, after all. Rome is a fantasy.

Near the end of my last visit, I found it, the Gregory Peck/Joe Bradley apartment at Via Margutta, 51. There’s a gallery next door at 51A. If there’s a man inside sitting behind his desk, approach him. You’ll know him when you see him. You’ll smile and he’ll smile, and you’ll point to the famous address, and before you can even ask the question in your broken Italian, he’ll smile wider and say “Vacanze Romane?” You’ll nod and smile and say “Sì.” By then if you’re very lucky he’s fished the key from his pocket and you’re saying “Grazie” again and again as he beckons you to the door. You’ll hesitate a second, then walk right through. Everything is just as you pictured it. All these years later and here you are at last.

A groomed gravel courtyard ringed with apartments and artists’ studios with windows two stories high. Cast iron gas lamps. Ornamental trees. Climbing ivy. The hill to the villas green and steep in front of you. A staircase half hidden to the left, eagle rampant across the lintel. There’s a wide brushstroke of darkening blue above it all, and the kind of late day quiet that settles on an empty house.

Up those stairs, off limits to gawkers and fanatics and movie buffs, is a little balcony, with an arbor just below it, and beyond it another short sweep of stairs with a wrought-iron railing curving up to Joe’s apartment door. Without moving—without even opening my eyes—I can see it all so clearly.

A city is what it does to you. On the Via Margutta, every one of us is beautiful. Every one of us lives forever. And Rome has all the time in the world.

Roman Holiday (1953)

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jeff_MacGregor2_thumbnail.png)