The Fall and Rise of a Modern Maharaja

Born to a palace but stripped of his livelihood in the 1970s, Gaj Singh II created a new life dedicated to preserving royal Rajasthan

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fb/ec/fbecd6e7-c7e5-43dd-ae87-ff727ab9a715/sqj_1601_india_palaces_01.jpg)

Gaj Singh II tells the story matter-of-factly, as if it might have happened to anyone: He was four when his father, the tall, dashing Hanwant Singh, crashed his plane and died. The boy was told only that his father had “gone away” and that he would become the 29th maharaja of the princely state of Jodhpur. On the day of his coronation, thousands of people celebrated in the streets. The air thrummed with the echoes of trumpets and drums, and the new king, resplendent in a tiny turban and a stiff-collared silk suit, was showered with gold coins.

It was 1952. Five years earlier, India had become independent through the transfer of power from the British crown to the successor states of India and Pakistan. Singh’s mother, Maharani Krishna Kumari, recognized a new reality. She sent her son to England to study at Cothill House and then Eton College. “She didn’t want me growing up in a palace, with palace retainers, thinking nothing had changed,” Singh, now 68, recalled recently.

Tall and mustached, with combed-back hair, Singh is usually photographed while at parties in a festive turban, holding a glass of champagne, mingling with celebrity guests like Mick Jagger and Prince Charles. But in person he appears frail. He walks with care, and his voice is low and gravelly. Often seen in jodhpurs, the trousers named after the seat of his former kingdom, he is this day dressed simply in a green cotton tunic and pants.

Although Singh visited India during school vacations, he returned home for good in 1971, only after earning a graduate degree in philosophy, politics, and economics from Oxford. He was 23, and things had indeed changed: Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was determined to strip the royal families of their titles and eliminate the “privy purses,” or allowances, that had been offered to them as recompense for disbanding their princely states after independence. Several royals, led by Singh’s uncle, the maharaja of Baroda, formed a committee to negotiate with Gandhi, asking that any changes in their circumstances be introduced gradually. But Gandhi ultimately prevailed. “We became the bad boys,” Singh said, shrugging his shoulders while not quite hiding the sting.

Stripped of his $125,000-a-year allowance, Singh needed to find a way to offset the maintenance costs of the palaces, forts, jewels, paintings, and cars—including a Rolls-Royce Phantom II—that made up his lavish inheritance.

Young, decisive, and armed with a handful of advisers, he formed trusts and companies to protect and reinvest his assets. While in Europe he’d seen how the nobility had turned stately homes into hotels and thrown open their magnificent gardens to ticketed tours. “That made me think: We can do it as well,’’ Singh said. He approached some of India’s best conservators and environmentalists. “I was more open to advice [than some other royals],” he added with a smile. “I took a chance.”

The chance he took—and its payoff—is manifest today throughout Jodhpur, in the state of Rajasthan. The five-centuries-old city is a fairy-tale maze of ornate entryways, ancient temples, and mysterious gated havelis, or mansions, many of which originated with Singh’s family. An ancestor, Rao Jodha, founded the city in 1459 as the home of the warrior Rathore clan of the Rajput community. Jodha’s descendants—Singh’s clansmen—still live here. The men are recognizable as Rajputs by their handlebar mustaches, the ends twirled to a fine point. Shiny gold hoops gleam in their ears. The women are draped in gauzy, bright-colored saris but cover their faces in public out of modesty.

Singh wasn’t the first prominent Indian royal to monetize his legacy. Rambagh Palace in Jaipur, with its ornate Mogul terraces and crystal ropes of chandeliers, was converted into a hotel in 1957. Udaipur’s Lake Palace, built in the 1700s as a summer residence for the kingdom’s royal family, started accepting luxury travelers in 1963. Built on a rocky outcrop in the middle of a glittering lake, the white marble palace appears from afar to float on water. Twenty years later it was immortalized by Hollywood in the James Bond film Octopussy.

Yet an untold number of royal properties in India have fallen into ruin. The Archaeological Survey of India, a government agency, attempts to maintain some, not always successfully. A 2012 government report found that even World Heritage sites were in disrepair, with their antiquities being smuggled out of the country.

The nationalization of monuments in independent India took place in part because many royals were unable to hold on to their inheritances. Some lacked the vision; lengthy court battles sidetracked others. After the glamorous maharani of Jaipur, Gayatri Devi, died in 2009, her family went to court over her $400 million fortune, which included Rambagh among many other palaces, an enormous jewelry collection, and an apartment in London’s exclusive Mayfair district.

The property fights sometimes became the last word on their legacies, tarnishing the reputation of India’s royals. But the problems had started right after independence when it became clear that royal wealth had been built on the backbreaking slave labor of the poor. Even as royals ruled from palaces with as many as 500 servants, their subjects led impoverished lives under a dehumanizing caste system that determined where they lived and what work they did. The royals also carried the taint of having sided with the British during the Indian fight for independence. Unlike their counterparts in Britain, they are today neither widely accepted nor widely respected.

Singh, to his credit, isn’t blind to how people like him were perceived then and may still be now. “There was a stigma,” he says. “It’s changing, but we suffered because of that.”

Unlike some sniping royals, Singh poured his energies into work. He first turned his attention to the massive Mehrangarh Fort, or Fort of the Sun, which looms 400 feet above Jodhpur. For decades, bats were the fort’s only permanent residents, and in the early 1970s Singh’s first income from Mehrangarh was from the sale of their droppings. His Mehrangarh Fort Trust sold the bat guano to chili farmers as fertilizer.

Inside the fort’s sandstone clasp are palaces, courtyards, dungeons, and shrines. Climb to the top for a breathtaking bird’s-eye view of the city. Just below, a part of the old city, Bramhapuri, unfolds in a sea of blue—a color, by some accounts, that Brahmans have painted their houses to distinguish them from others’. Beyond lie temples, lakes, and the distant sand dunes of Thar, or the Great Indian Desert.

Singh donated nearly 15,000 items from his personal collection to the trust to create a museum within the fort. Opened in 1974, it’s a dazzling selection with broad appeal. Young men snap selfies by the gleaming swords and daggers of the armament gallery. Couples take a quiet interest in the line of gently swinging royal baby cradles. Tourists gawk at 16 exquisite howdahs—carriages for elephant riders. Some are fashioned of silver.

Today the fort attracts more than one million paying visitors a year. Admission fees support a staff of nearly 300, including security guards and crafts-persons, and Mehrangarh is self-sustaining.

Singh could have left it at that, says Pradip Krishen, an environmentalist. But Singh recruited Krishen to help turn a 172-acre rocky wilderness below the fort into a park. The area had been invaded by thorny mesquite trees native to the U.S. Southwest. Wild animals roamed freely, and homeless families camped there. “It would have been easy for him to sell off the land thinking, it’s wasteland anyway—it’ll make me big bucks,” said Krishen. But after a decade of work, the wilderness has been replaced by walking trails, and visitors to Rao Jodha Desert Rock Park can see roughly 300 different species of plants and many varieties of birds, snakes, and spiders, all in their natural habitat.

Historic sites in India are often littered with trash, but Mehrangarh is striking in its pristine cleanliness. Karni Jasol, director of the Mehrangarh Fort Museum, makes sure it stays that way. From his office in the Autumn Palace of the fort, with a computer at his fingertips, Jasol manages everything to the smallest detail. He is very recognizably a clansman of Singh’s, with a sharp nose, dark mustache, and careful manner of speech cultivated at Mayo College, an exclusive private boarding school modeled after Eton, to which India’s most privileged families often send their sons.

Jasol’s own sensibility was shaped in part by nine months he spent at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries of Asian art in Washington, D.C. This experience led to “Garden & Cosmos,” Mehrangarh’s first major exhibition, 56 royal paintings from Singh’s personal collection. The artworks, dating from the 17th to 19th centuries, are sweepingly large and vibrantly colored. Some are amusingly fanciful—in one, the Princess Padmini zooms through the air like Supergirl. Others show male royals in their downtime—swimming and enjoying wine on a moonlit terrace.

The exhibition made its award-winning debut at the Smithsonian before traveling to three continents. The Guardian newspaper, writing about its appearance at the British Museum in London, hailed it as “the most intoxicating show of the year.” The exhibition was a milestone for Singh, helping establish his credentials globally as a serious conservator.

Singh never lived in Mehrangarh, but converting Jodhpur’s 347-room Umaid Bhawan Palace into a hotel meant opening the doors of the home where he has lived most of his life. Singh launched the hotel in the 1970s, and in 2005 the Indian luxury hotel chain Taj stepped in, putting the palace on the map as one of the world’s great destinations.

As a child, Singh played badminton in the marble halls of Umaid Bhawan and hide-and-seek under its hundred-foot-high dome. The palace bustled with so many people at any given time that meals were laid out for at least 30 just to be safe. Then, when Singh had children of his own, they roller-skated down the same halls and threw disco-themed parties for friends in the palatial rooms. They were also known to stand on the very top floor and hurl spitballs down at passing visitors—a misdemeanor that, on being discovered once, ended with them being sent to bed with bread and water.

Originally, the palace zenana was the exclusive purview of women. It was where they lived. But the zenana wing is now the primary residence of the Singh family. It has its own garden, as big as a public park, with wild parrots and strutting peacocks. Lalique glassware and antique furniture adorn the high-ceilinged rooms. Singh’s office adds some homey touches. It is full of handsome art, but the largest painting is a portrait of his two children when they were young. Cushion covers are embroidered with images of his favorite breed of dog—Jack Russell terriers. The family has four of the dogs, all named after alcoholic beverages. Singh’s personal favorite is a rambunctious little fellow named Vodka.

Singh’s grandfather, Umaid Singh, father of Hanwant Singh, laid the foundation stone of the palace in 1929 on a hill that rose hundreds of feet above the surrounding plains. Fondly remembered in his New York Times obituary as having once visited England for polo season with four wives, seventy ponies, and a hundred servants, Umaid Singh commissioned the palace to “reflect the prestige of the state,” writes Giles Tillotson in one of his books on the family. Gaj Singh makes a point of saying in interviews that Umaid Bhawan was built as an act of charity—to give jobs to the poor to stave off famine during a drought. The 3,000 half-starved people who toiled to build the palace for well over a decade may not have seen it that way, of course.

Designed by the British architect Henry Lanchester, the palace is a marble and sandstone wonder in a style sometimes called Indo-deco, surrounded by 26 acres of gardens. It has a central hall and intricately carved pillars crowned with a finely detailed dome. Visitors walking through the hall tend to bump into things, as they’re unable to take their eyes off the ceiling. Rooms fan out on all sides. An elevator with a sofa inside—where the younger royals would sneak in for a cigarette break—takes hotel guests up to the top floor, which is filled with murals by the Polish artist Stefan Norblin. The top-end suites, where the king and queen originally lived, have pink marble, silver ornaments, and a sunken bathtub.

During a recent visit, the British director Gurinder Chadha was in the midst of an eight-week shoot for her film Viceroy House, which stars Gillian Anderson of The X-Files and Hugh Bonneville, best known for playing the patriarch of another splendid property in Downton Abbey. Films are shot at the palace so frequently, it’s said, that visiting friends of the Singhs are often invited on board as extras.

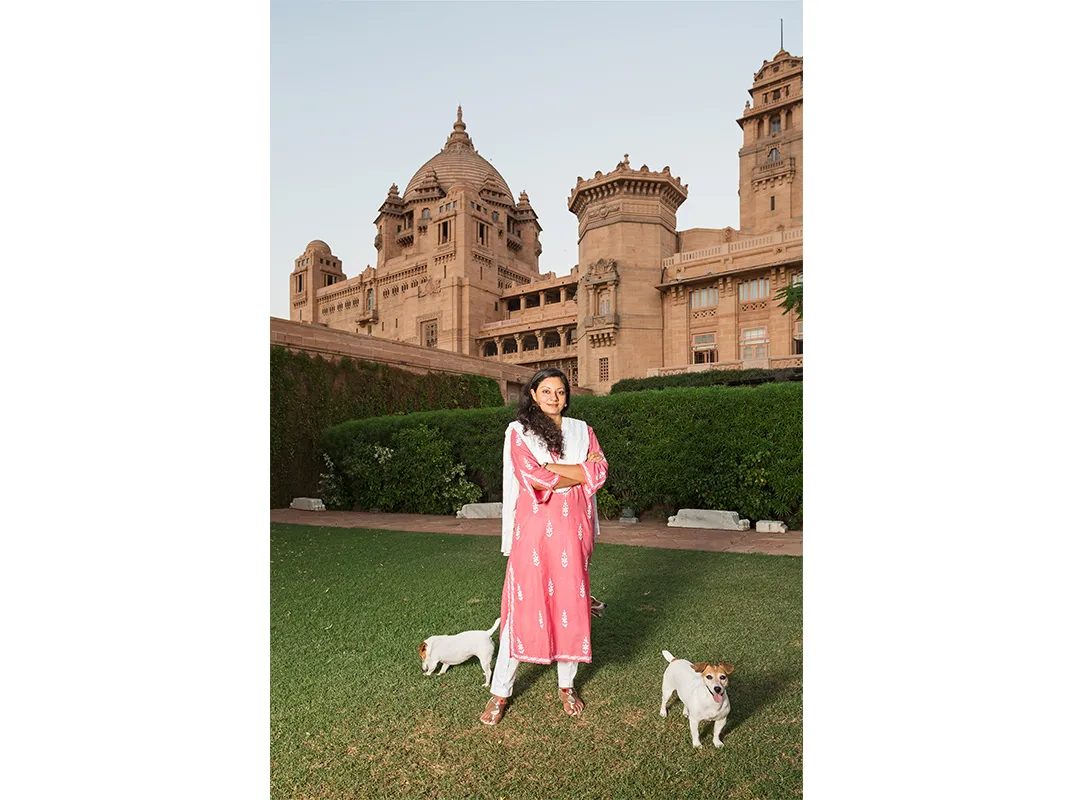

Although final decisions on the family’s property matters rest with Singh, he has involved his 41-year-old daughter, Shivranjani Rajye, in the business. The two are close, but she’s the first to say that her new role wasn’t what either of them had planned.

Singh also has a son, Shivraj. Though he is a year younger than his sister, Shivraj, as the male heir, will inherit his father’s title and all his properties. He was thus also being groomed to take over his father’s work until in 2005, at the age of 29, he suffered a head injury playing polo and slipped into a coma. “It threw one completely,” Gaj Singh says with a sigh. “It was a big derailing emotionally and organizationally.” Although his son is now much better—in a “good state,” Singh says—it is Shivranjani, petite, quick to smile, and with a profusion of long black hair that flows down her shoulders, who is involved in the museum trust. She also runs Jodhana Properties, an umbrella business that manages the family hotels and oversees the music festivals now held in the forts.

Shivranjani is the least widely known of the royal family. Unlike her brother, whose social life was once well documented in the tabloids, she has virtually no media presence. She’s hardly a wallflower, though: Warm and charismatic, she is seen as more approachable than other members of her family. It helps that wherever she goes, her happy-go-lucky Jack Russell, Fifi (named after a cocktail) follows.

Just as Singh’s mother sent him abroad, so too did he take his children away from the palace, hoping to give them something like a regular childhood. The family spent the children’s early years on the Caribbean island of Trinidad, where Singh was a diplomat.

Shivranjani was six when they returned to Jodhpur. The rail station platform was packed with well-wishers, and her father was carried away in a celebratory tide. It was the first time, she says, that she realized he was a public figure. “I just bawled,” she recalls over tea in Umaid Bhawan’s Heritage Room. “But my brother loved it. He knew this was a part of his life.” The children studied in India before being sent to prep schools in England, as their father had been. Shivranjani acquired a degree in anthropology at Cambridge before a change of focus took her to New York to study filmmaking at the New School.

The decor of the Heritage Room, which is open to guests, demonstrates the different positions male and female members of India’s royal families occupy. The most prominent portraits are of Shivranjani’s great-grandfather, grandfather, and father. There is even a life-size one of her brother, Shivraj, then a plump-cheeked teenager.

Well aware of this disparity, Shivranjani has spearheaded a change in the disbursement of the family inheritance. “The son will inherit the title and properties,” she says, “but businesses can have many heads.” Asked if she thinks her family will ever modify the rules of succession, she says it is unlikely. “A girl will never inherit over a boy,” she says. “I don’t have a problem with that because it’s an old [system]. But if you say a boy is everything and a girl is nothing, well, I have a problem with that!”

Shivranjani’s focus, like that of her father, is on opening up the properties to a wide range of people and activities. Culture and traditions matter to the Rajputs, and they also matter to the Singhs. The family is running a business but also strengthening its legacy. “My father inherited a crumbling fort,” says Shivranjani. “But by the time I started working [with him], we had a ticket income. Now I have a corpus to work with so I can do new things.”

One is the music festivals. They showcase Rajasthani musicians, and in recent years they have also hosted Sufi singers and flamenco artists who perform late into winter nights in the light of hundreds of clay lamps.

The first of the festivals was held nine years ago in another of the family’s properties, Ahhichatragarh, or Fort of the Hooded Cobra, in Nagaur, a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Jodhpur. The early 18th-century fort is flat and sweeping, with graceful gardens and a hundred fountains. With grants from the Getty Foundation and the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, architect Minakshi Jain has been restoring the fort, and specialists are bringing wall paintings back to their original splendor. While the work is ongoing, some restored murals can be viewed. They are small, faded, and intimate portraits of women, long-haired, almond-eyed, and bejeweled, playing games, smoking hookahs, combing their hair, and bathing. Unlike Mehrangarh, this fort has no museum pieces. The palaces are empty. There are still bats and snakes. But the emptiness gives the place a magical quality.

Singh and his team are working on several new conservation projects: two cenotaphs (burial monuments); an early 20th-century building known as Ship House, which is being reimagined as a maritime museum; and an 18th-century Mogul garden on the banks of a Jodhpur lake. Asked which is his favorite family property, Singh answers in a way that offers an insight into the secret of his successful transition from a royal in the eyes of some to a serious conservator in the eyes of many. “You can’t have forts and palaces without people,” Singh says. “People make it all real.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1601_India_Contrib_02.JPG)