In a Remote Alaskan Town, a Centuries-Old Russian Faith Thrives

Residents of Nikolaevsk remain true to the traditions of their ancestors, who fled religious persecution in the 17th-century

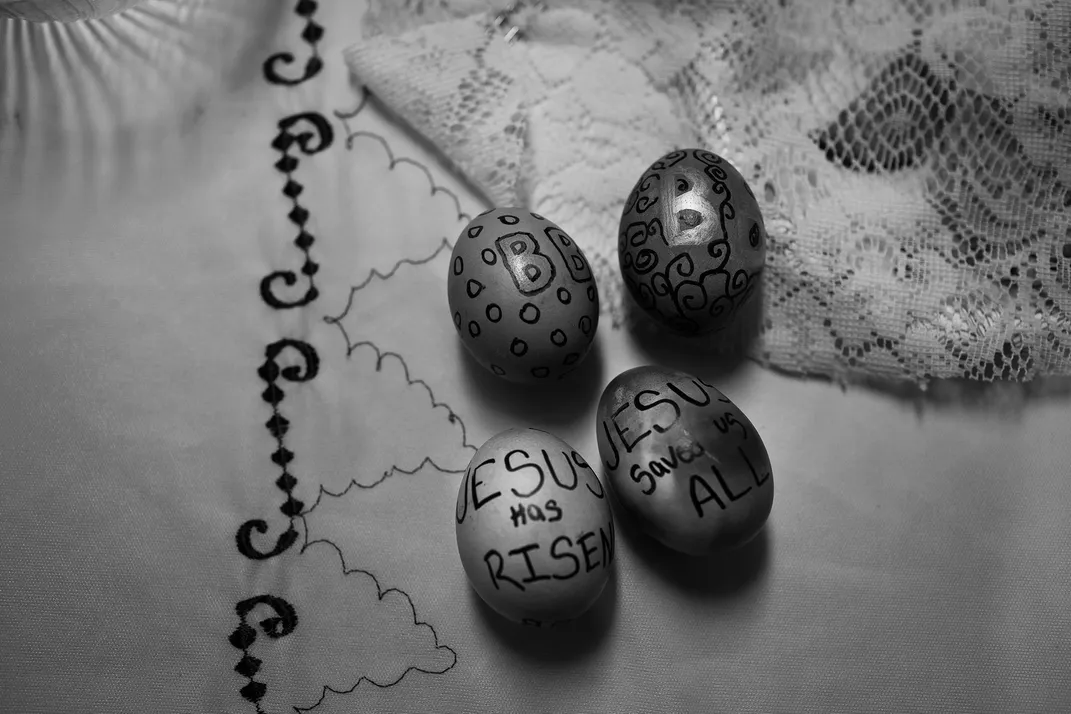

In 1968 five families settled in Nikolaevsk on the Kenai Peninsula. They belonged to a religious group known as the Old Believers—a sect that split from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1666 in opposition of state-ordered reforms. Their ancestors fled persecution to Siberia, China, Brazil, Oregon, and then Alaska. Today, there are 350 residents in the community. “They started a journey that continues with new generations. They stand true to their tradition,” says Spanish photographer Andrea Santolaya, who documented their celebration of Pascha, Russian Easter, for her ongoing project “Alyeska, The Last Frontier.”

Read Also: Tracing Alaska's Russian Heritage

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.