Sacred and Profaned

Misguided restorations of the exquisite Buddhist shrines of Pagan in Burma may do more harm than good

As we rattle along rutted dirt tracks in a battered jeep, Aung Kyaing, chief archaeologist of Pagan’s breathtaking 1,000-year-old Buddhist temples, points out an enormous pentagonal pyramid sparkling in the morning sunlight, dominating this arid central Burma plain.

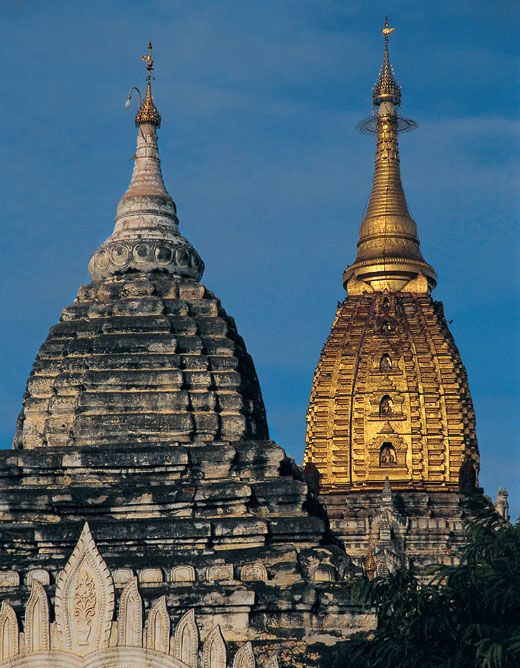

“Dhammayazika,” he informs me as we bounce past a golden, bell-shaped dome with red banners and a flashy marble walkway. “Secretary Number One paid for the restoration himself.” Secretary Number One is Gen. Khin Nyunt, one of the two strongmen leading Burma’s repressive military junta. Kyaing, an affable scholar dressed in an immaculate white shirt and green longyi, the traditional wraparound skirt favored by both Burmese men and women, is showing me an archaeological disaster—the best and the worst of the government’s recent efforts to restore the ancient temples.

In 1996, the junta invited sponsors across Asia to donate money to help the Burmese rebuild the crumbling temples, but they spurned any professional assistance from international conservators. The resulting hurried and often sloppy restorations have risked destroying the very treasures that make Pagan unique. “The restoration campaign is catastrophic,” says Pierre Pichard, a French archaeologist long familiar with Pagan.

Like many of Afghanistan’s archaeological treasures, Pagan’s temples may fall victim to politics. But there are signs of hope. Pagan attracts nearly 200,000 foreign visitors a year, 12,000 of them American, despite the U.S. government’s imposition of economic sanctions in April 1997 and the country’s repressive regime. With the May release of Burmese dissident and 1991 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, 57, from house arrest, the government has signaled, if not a willingness to back away from its harshly antidemocratic stance, at least a recognition of the importance of tourism and foreign exchange. If the change in attitude continues, many temples could be saved—at least that’s the hope of archaeologists like Pichard.

On this vast lowland plateau at a sweeping bend in the Irrawaddy River 300 miles north of the capital city, Rangoon, temples, domed pagodas and gilt spires create a surreal landscape. At the height of the Pagan Empire in the 13th century, there were some 2,500 temples; now, due to earthquakes and neglect, there are 300 fewer. Still, the overall effect remains awe-inspiring. Originally built by kings and subjects intent upon earning better lives in future incarnations, the temples were the seat of a dynasty that extended over an empire more or less the configuration of present-day Burma. (In 1989, the military dictatorship reverted to precolonial names—for them this is Bagan, Myanmar. But the U.S. State Department continues to use the names Pagan and Burma, as do many other organizations protesting the tyrannical government.)

Many of the temples in Burma were built to house relics of Buddha, Indian Prince Siddhartha Gautama, who some 2,500 years ago, renounced his wealth and taught his followers that they could experience enlightenment directly, without help from priests. The religion he founded now boasts some three quarters of a billion adherents, most of them in Asia. One of Buddha’s teeth, according to legend, is embedded under the graceful bell-shaped stupa (which became a model for all future stupas in Pagan) at Shwezigon Pagoda. A strand of his hair is purportedly preserved inside the stupa that tops the ShwezigonTemple (hence its name “shwe,” or “golden,” and “zigon,” meaning hair), which offers one of the highest vantage points in Pagan. There are no tombs, however, since Burmese Buddhists cremate their dead.

For a sense of Pagan, picture 2,000 cathedrals and churches of all shapes that vary in height from barely 12 feet to more than 200 feet, all squeezed into a parcel of land about three quarters the size of Manhattan. (At 200 feet, the ThatbinnyuTemple is about as high as Notre Dame in Paris and was built at roughly the same time.) Apart from the sheer number of temples in Pagan, the ancient city also has the greatest concentration of Buddhist wall paintings in Southeast Asia. As Scottish anthropologist James George Scott wrote in 1910 of Pagan: “Jerusalem, Rome, Kiev, Benares, none of them can boast the multitude of temples, and the lavishness of design and ornament.”

The citizens of Pagan began their temple-building in the tenth century, more than 100 years after the kingdom was founded. In the 11th century, Pagan’s King Anawrahta returned from a pilgrimage to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), intent on converting his subjects from the animistic worship of nats, or spirit gods, to the austere Theravada school of Buddhism, which directs believers to attain enlightenment through meditation and meritorious deeds. About the same time, King Anawrahta began taking full advantage of the city’s strategic position on the Irrawaddy as a trading port linking China and India. Under the rule of Anawrahta’s son, Pagan continued to prosper, and the population swelled to 100,000 inhabitants. The nation’s overflowing coffers went into building elaborate Buddhist temples, monasteries, libraries, and housing for pilgrims. The court was so wealthy that children of nobility played with silver and gold toys.

By the time a king named Alaungsithu came to power in 1113, Pagan traders had become so skillful on the seas that the king himself captained an oceangoing ship with 800 crew on a trading mission to Ceylon, 1,500 miles southwest across the Indian Ocean. The ambitious explorer-king was also something of a poet, dedicating ShwegugyiTemple in 1131 with the lines, as translated from the Burmese: “I would build a causeway sheer athwart the river of samsara [worldly cares], and all folk would speed across thereby until they reach the Blessed City.”

Unfortunately, Alaungsithu’s treacherous son Narathu, impatient to rule, smothered him to death on a Shwegugyi terrace. After that, Narathu killed his uncle, as well as his own wife and son, poisoned an older half brother who was heir to the throne, and then married one of his father’s mistresses. When she complained that he never washed, the new king personally dispatched her with a sword thrust through her heart. When it came to ensuring his own afterlife by temple-building, the psychopathic Narathu was a stickler for precision brickwork. He insisted that the bricks in the 12th-century DhammayangyiTemple, the largest in Pagan, be set so close together that a needle could not pass between them. He was eventually done in by assassins.

The Pagan Empire began to disintegrate in 1277 with its ignominious defeat at the hands of Kublai Khan’s army at Ngasaungsyan, near the Chinese border 400 miles to the north. When the Burmese refused to pay tribute to the Mongol ruler, Khan sent his 12,000-horse cavalry to invade their kingdom. Marco Polo, traveling with the Mongols, wrote of the bloody debacle in which Pagan’s soldiers, on foot and atop elephants, were lured into a forest and slaughtered. Though scholars debate whether the Mongols ever occupied the city, most agree that by the end of the 13th century, religious zeal had gotten the best of the Pagan kings. By spending so much money on temples and turning so much land over to a tax-exempt religious order, they had bankrupted the country.

Pagan went into gradual decline. The monasteries were open, and pilgrims journeyed there, but the temples were neglected, and plundered by treasure hunters who eviscerated statues and dug into stupa bases searching for precious stones. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, a wave of Europeans removed sculptures and carvings to museums in Berlin and other cities.

Burma became a British colony in the late 1880s but regained its independence in 1948. Then followed more than a decade of civil turmoil when a weak democracy broke into factions, which fought back and forth for control of the government. The nation has been ruled for the past 40 years by a series of uncompromising military dictators. When Aung San Suu Kyi’s opposition party, the National League for Democracy, won 80 percent of the vote in 1990 in elections ordered by the junta to quell major civil unrest and to gain international legitimacy, the government annulled the result and imprisoned Suu Kyi and hundreds of dissidents. Since her release eight months ago (because of pressure from the U.S. government, the European Union, Burmese dissidents living abroad and international human rights organizations), the junta has freed more that 300 political prisoners, though more than 1,000 opponents of the regime remain in jail. The junta has permitted 50 National League offices to open, and Suu Kyi has been allowed limited travel to rally support for democratic reform. Nonetheless, according to Human Rights Watch, severe political repression, torture, forced labor and the drafting of children into the army remain. In an October report on religious freedom, the State Department excoriated Burma for its ardent persecution of Muslims and other minorities.

Although Suu Kyi continues to insist that U.S. sanctions be maintained, she is encouraging targeted humanitarian assistance. Along these lines, the U.S. Agency for International Development is sponsoring a $1 million program to fight HIV/AIDS in Burma, an epidemic ravaging the population. But tourists, Suu Kyi says, should boycott the country until the military rulers demonstrate tangible progress on democratic reform. However, even some members of her own party disagree, pointing out that the money that goes toward guest houses, restaurants, tour guides, drivers and local artisans generates desperately needed income in a country where many families live on $5 a day. “If the tourists don’t come, women in textile factories will lose their jobs,” Ma Thanegi, a journalist and former aide to Suu Kyi, told the New York Times recently. “They are the ones who suffer, not the generals.”

Others contend that encouraging tourism could reduce Burma’s dependency on the deeply entrenched opium trade and the rampant logging that is rapidly deforesting the once lush woodlands. However misguided, the government’s current race to restore temples is part of a broader campaign to exploit Pagan’s tourism potential. In the meantime, local residents and pilgrims continue to use the temples as they always have, for quiet meditation and worship, and as communal parks.

But the temples themselves have changed. Everywhere, it seems, temples with new bright pink brick and thick concrete mortar stand out in shocking contrast to the ancient redbrick exteriors and carved sandstone facades. Many temples are being newly built or reconstructed from the ground up rather than restored—using concrete and other materials that damage both the structures themselves and the fragile wall paintings inside. According to Minja Yang, deputy director of the World Heritage Site program for UNESCO in Paris, more than a thousand temples were badly restored or rebuilt in 2000 and 2001.

Since 1996, when the junta invited donations, devout Burmese from Secretary Number One on down, as well as hundreds of Singaporean, Japanese and Korean Buddhists—a total of some 2,000 contributors—have poured millions of dollars into the reconstructions. Their goal, too, is to gain religious merit in this life and in future incarnations. Although the work is widely condemned, the Burmese authorities still press for donations.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the French archaeologist Pichard worked with UNESCO and the United Nations Development Program to train Burmese conservationists. The restoration program was moving ahead, but the junta saw an opportunity to increase revenue by launching a cheaper conservation plan, so they shut down the UNESCO program. Pichard, who recently completed the eighth volume of his definitive Inventory of Monuments at Pagan, accuses authorities of churning out “Xerox stupas,” carbon-copy temples based on scant archaeological evidence. “They’ve rebuilt hundreds of buildings on ruins that are little more than mounds of rubble,” he says, “and they take a percentage on every one.” Very little of the donated money finances restoration of the precious wall paintings.

“The cement they’re using contains salts that migrate through the brick and damage the murals,” adds Pichard. The liberal use of concrete also makes the buildings rigid and far less likely to withstand earthquakes. He says that in a 1975 earthquake that registered 6.5 on the Richter scale, temples that had been reinforced with concrete in earlier restorations collapsed in huge chunks, some weighing a ton, smashing everything beneath. Without concrete, the bricks tend to fall one by one, causing far less damage, he says.

UNESCO and other cultural organizations recommend halting the poor-quality reconstruction and, using international funding, bringing in independent experts to offer technical assistance. But the junta has made it clear that it rejects all international oversight or advice.

Unlike the damage caused by recent restorations, the mural-cleaning and conservation projects conducted by U.N. and Burmese teams in the ’80s and ’90s have proved remarkably durable. Early one morning, I arrange for a horse-cart ride to the 12th-century GubyaukgyiTemple, an imposing pyramid of redbrick with elaborate carvings topped by a tapering, corncob-shaped tower called a sikhara. Gorgon masks with garlands of pearls pouring out of grinning mouths form a frieze that rings the temple’s exterior. Inside, on the walls, tigers and fantastic beasts square off with snout-nosed, yellow-faced demons. In the niche of one window, I can just make out a pair of lithe dancers twirling arms and legs seductively in shadow. These are among the oldest and, after careful and proper restoration, the most vivid paintings in Pagan.

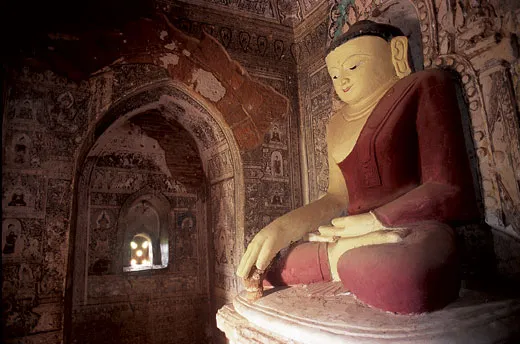

In marked contrast, at Leimyethna, a 13th-century temple about a mile away, I am appalled to see that a donor has inscribed his name in red paint over 800-year-old wall paintings. Equally jarring, a new gilt statue of a seated Buddha is surrounded by incongruously jazzy paintings of flowers, vines and lotus blossoms in bright Mediterranean pastels that look like poor copies of works by Henri Matisse or Raoul Dufy.

When the Burmese archaeologist Kyaing and I arrive at Nandamanya, a 13th-century terraced brick temple topped by a bell-shaped dome, we slip off our sandals at an intricately carved doorway and step barefoot into the cool interior. Weak sunlight filters through a pair of stone windows perforated in diamond-shaped patterns. When Kyaing turns on his flashlight, the dimly lit walls erupt in extravagant color, illuminating one of the best murals in Pagan: exquisitely detailed scenes of Buddha’s life painted in the mid-13th century.

One Nandamanya panel depicts Buddha preaching his first sermon in a deer forest embellished with intricate yellow flowers and green foliage. Painted fish with individual scales are so well-preserved that they gleam in the artificial light. An illustrated series of half-naked women, daughters of the evil demon Mara sent to tempt Buddha, remain mildly shocking, though hardly “so vulgarly erotic and revolting that they can neither be reproduced or described,” as Charles Duroiselle, a French expert in Burmese inscriptions, huffed in his 1916 description of the temple. Some of the paintings are riven with cracks. “Earthquake damage,” says Kyaing, referring to the 1975 tremor. “This temple was spared, but the murals were damaged. We are trying to leave them untouched except for cleaning and filling cracks with harmless epoxy resin.”

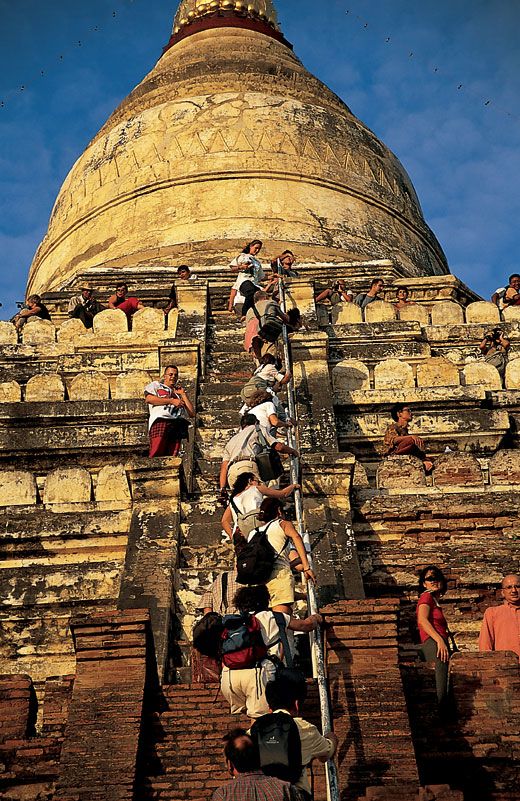

After Kyaing drops me off at my riverside hotel set among several temples, I rent a bicycle and pedal out to the 11th-century temple known as Shwesandaw, a milesouth of the city gate, a prime vantage point for catching the sunset and, for locals, netting Western dollars. At the entrance, eager vendors sell postcards, miniature Buddha statues and jewelry. I climb five flights of steep exterior steps to join other camera-toting pilgrims crowding the narrow upper terrace for a sweeping view of the milewide IrrawaddyRiver, where fishing pirogues scurry out of the path of a steamer ferry belching thick, black smoke. The fading light burnishes the hundreds of temples dotting the plain in shades of deep umber.

Pedaling lazily back to the hotel, I pass lantern-lit stalls where vendors are busy setting out silk, woven baskets and lacquer boxes in preparation for a religious celebration that will last three weeks. Fortune-tellers, astrologers and numerologists set up tables in anticipation of brisk busi ness from their many deeply superstitious countrymen. Squatting in front of a restaurant, a pair of old women puff on fat cheroots, crinkling their eyes in amusement as a young girl runs alongside my bike. “Want to buy a painting?” she asks. “My brother paint from temple. Very cheap.”

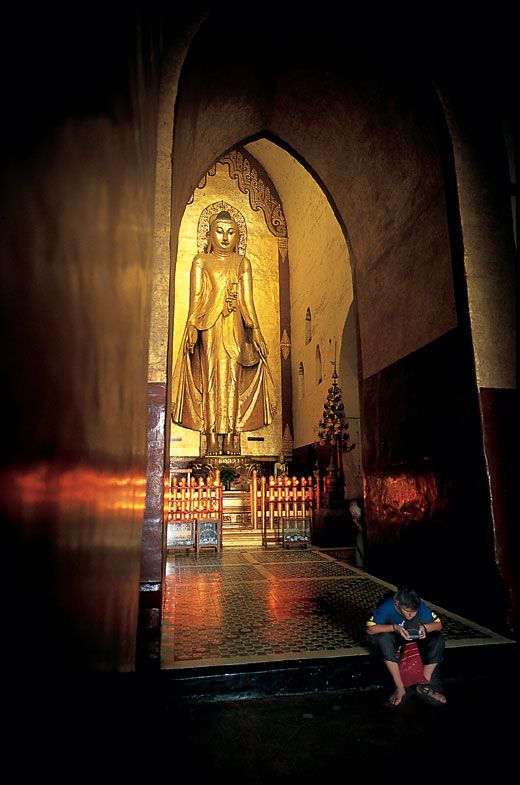

The next day, I sit on a bench encircling a gargantuan banyan tree in a courtyard outside the beautifully restored AnandaTemple, the largest and most revered in Pagan. I watch several young women sweep the courtyard industriously, a task that earns them 100 kyat (about 17¢) a day plus a ration of rice.

“No one is forced to work on the temples,” Kyaing says later when I ask if the women are forced laborers. “We Burmese enjoy doing meritorious deeds as a way to escape suffering,” Kyaing continues. “That’s why we clean temples and restore pagodas—so we can have a good life in the future. Even our Buddha had to go through many lives. Sometimes he was a king, sometimes an important minister of state, sometimes no one at all.”

Like Buddha, Burma is overdue for another, hopefully more democratic, reincarnation, one in which the restoration of its ancient sites will proceed more thoughtfully. As critical as Pichard and other scholars are of current reconstructions, they are not suggesting that the Burmese, and other Buddhists, be denied religious merit through donations for restoration work. Surely, they say, there is more merit in properly preserving the legacy of the country’s ancestors than in mass-producing fake stupas using techniques that risk destroying irreplaceable art.

If a more responsible conservation program is not undertaken soon, Burma’s transcendent mystique will unquestionably suffer irreparable harm. But if international pressure led to freedom for Aung San Suu Kyi, there’s hope a similar campaign can rescue Pagan.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.