John Wang has a lot on his plate. Five years since launching an open-air food market in the heart of Queens, New York, he’s facing the very real possibility that the COVID-19 pandemic will derail what was bound to be another incredible summer of international flavors, ranging from Filipino dinuguan to Haitian diri ak djon djon.

An ex-corporate attorney, Wang had no culinary work experience prior to launching the Queens Night Market in 2015—just fond memories of the night markets he visited during his childhood summers in Taiwan. As a youngster, he became captivated by the electricity given off by the crowds and vendors in a public setting, where people gathered and mingled over food until the sun came up the next morning. He wanted to reflect that vibe in the Big Apple, but adapted it to fit its multicultural melting pot. “We decided that if we were going to do that in New York City, we would do something that resonated and spoke more to New York City,” says Wang.

Last year, an average of 13,000 attendees came per night rain or shine to the market, held on Saturday nights from mid-April through the end of October (with a short break for the U.S. Open) behind the New York Hall of Science in Flushing Meadows Corona Park. Queens is the most diverse county in the United States, and the variety of foods representing more than 90 countries is proof. The market’s a multigenerational gathering, too, as family members share in the work of overseeing pots and counters and attendees of all ages eye the grills, skillets and fryers in vendors’ tents. Here, visitors can eat their way around the globe, sampling Jamaican jerk chicken, Indian dosas, Cambodian amok, Salvadoran pupusas, Tibetan momos, Polish pierogis, and Norwegian fiskegrot.

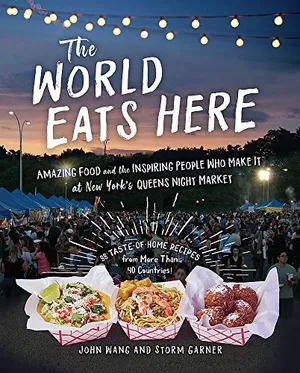

While waiting out the pandemic, those who love the market, and even those who have just heard about it for this time, can direct their focus to a new cookbook that tells the story behind the bazaar. The World Eats Here: Amazing Food and the Inspiring People Who Make It at New York’s Queens Night Market contains 88 recipes from just over 50 vendor-chefs whose cuisines reflect more than 40 countries.

“It’s nice to have something that’s out there, in a physical form, that keeps us connected to New York City, and maybe even the world,” says Wang.

Co-authored with his wife, Storm Garner, a filmmaker and oral historian, The World Eats Here is more than a recipe collection. It is also a biographical account. Each recipe is paired with a profile of the Queens Night Market vendor who makes it, describing the cook’s personal history and motivations for starting a food-related business. These narratives were derived from interviews Garner conducted for her thesis, part of an oral history master’s program at Columbia University.

“We wanted you to know about their culinary achievements, but I thought it was really important to get to know them as people outside of the food industry also,” says Garner.

Wang played the role of intermediary between the vendors and editors, identifying ingredients, measurements and techniques that were otherwise passed down by experience or word of mouth and translating them into written and tested measurements and directions. “We tried as best as we could make sure that [the dishes] were all replicable at home,” says Wang. Alongside color photographs of the market and key players, the cookbook’s illustrations of vendors, dishes, ingredients and preparations give it a scrapbook feel. On other pages, visual aids provide step-by-step guidance in more methodical recipes for foods such as Ukrainian blintzes and Mexican huaraches.

The World Eats Here: Amazing Food and the Inspiring People Who Make It at New York’s Queens Night Market

Welcome to the Queens Night Market, where thousands of visitors have come to feast on amazing international food—from Filipino dinuguan to Haitian diri ak djon djon. The World Eats Here brings these incredible recipes from over 40 countries to your home kitchen—straight from the first- and second-generation immigrant cooks who know them best.

The experiences of Queens Night Market vendors are as varied as their cuisines. Some are all-in with their food businesses. Others have day jobs and work in various professional backgrounds—medical, finance, law, hospitality, education and tech, to name a few. For them, their food entrepreneurship could be a hobby or side gig. Still others do it to share their culinary heritage with the public or spend quality time with their families while working at the market. Participating vendors hail from all five boroughs.

Daniel Nalladurai, a native New Yorker of southern Indian descent, and his wife, Helena Kincaid-Nalladurai, who also run a film production company, were interested in entering the food industry. The couple approached Daniel’s parents about sharing his mom’s recipe for chicken curry with dosa (the latter is a rice pancake made from a fermented batter that looks similar to a crepe) for preparing and selling at the Queens Night Market. It has resulted in the creation of what’s now Dosa Mama, a side business with Daniel, his wife and his mother handling the cooking.

Daniel, who grew up and still lives in Flushing, finds that the night market reflects what the city is about, even in the midst of seeing neighborhoods change. “We feel [it’s] like the true representation of what New York is and what New Yorkers are.”

Wang’s vision was shaped by New York City’s diverse population and its upward cost of living. The market was to be more of a social mission than a cash cow. “I wanted it to be community based, and affordable,” says Wang.

The rules of the market dictate that all food items cost no more five dollars (a few goods are exempted and can charge an extra buck.) As for vendor fees, Wang says he figures out the costs to operate the market every night and divides that amount among the expected number of vendors.

Trinidadian Sean Ramlal runs Caribbean Street Eats with his wife, Savatree Singh, and the Flushing family operates this side business in New York City’s food truck and market scene; at the Queens Night Market, their fried shark sandwich, a Trinidadian street food, sells fast. He thinks that the market does well because of its family-friendly atmosphere and international variety. It doesn’t hurt that it is held in Queens. “You have everybody wanting to come and taste foods from different countries,” says Ramlal. “[It’s] very unique to have a place like that.”

Wang has been happy with the market’s growth in just five years. “The first year, we were in a little corner of a parking lot and now we’ve taken up close to three or four football fields worth of space,” he says. “The number of countries we represent through our vendors is increasing.”

2020’s planned culinary map includes more than 50 vendors—new and returning—gastronomically representing the Americas, Europe, Africa and Asia. The Caribbean island of Dominica is planned to make its debut. Other coinciding food-featured countries will include Antigua, Bolivia, Cambodia, Egypt, Hungary, Mexico, Myanmar, Norway, the Philippines, Venezuela and Sudan.

To date, the market has helped to launch 300 New York businesses. Like many food purveyors across the country though, the Queens Night Market vendors’ livelihoods have been affected by the coronavirus pandemic in various ways. Some have had to work from home and seen sales plummet. Restaurant owners have either shut down operations or switched to takeout and/or delivery-only service.

Participants Valentin Rasneanski and his wife, Liia Minnebaeva, of Wembie, a bakery known for their Russian and Eastern European pastries, enjoy that the market is a friendly community setting, where they can test out recipes. “It’s a nice place to be,” says Rasneanski.

At the Queens Night Market, the Bensonhurst, Brooklyn-based couple is known for Liia’s Bashkir farm cheese donuts—a childhood treat from her youth in Oktyabrsky in western Russia that is featured in the cookbook. As for her husband, the cookbook also includes his Moldovan family’s recipe for plăcintă, a round or square shaped cake with fillings such as a soft cheese.

The couple, who met while working at a restaurant in New Hampshire, had applied for a wholesale license to grow their business, but their plans are now on hold. They’re staying positive. “Whatever happens to us right now will make us stronger and perform better in a better way,” says Rasneanski.

Bronx resident Sokhita Sok credits the market in her starting Cambodia Now. Through the Queens Night Market residency program, she established a food kiosk within the Falchi Building in Long Island City, where she sold lunch choices of chicken skewers, cha kroeung and Cambodian curry noodle soup. Its operation there ceased on March 18. “Eventually, we’ll come back up at some point, but it’s going to be a long haul,” she says.

While the pandemic has put the re-opening of the market on hold, Wang is involved with Fuel The Frontlines, which hires Night Market vendors to provide meals for healthcare workers at Queens hospitals and EMS stations; Queens County is home to the largest number of COVID-19 cases in the country. Garner is now remotely interviewing vendors about their experiences in the COVID-19 pandemic and will contribute some stories to the Queens Memory COVID-19 Project. Proceeds from cookbook sales will be divided between the oral history project and the night market.

Wang and Garner, who reside in Manhattan, view the cookbook as a strong visual representation of the market. Wang notes that attendees can revisit their experience through its pages and try their hand at the recipes. Garner thinks that it’s a way for home cooks to expand their culinary repertoire, and get to know vendors through what they cook.

“It’s not a perfect substitute, but it’s the best we can do for now,” says Wang.

Domloung Chenng (Carmelized Sweet Potatoes)

Recipe from Sokhita Sok of Cambodia Now

Makes 5 servings

1 tablespoon white limestone paste

2 pounds Japanese sweet potatoes

8 ounces solid palm sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1 1/3 grated fresh coconut (frozen is fine)

1/4 cup coconut cream

1. Pour 5 quarts (5L) water into a large bowl or pot and mix in the limestone paste.

2. Peel the sweet potatoes and cut into 3 x 2 x 2-inch strips. Soak in the limestone water for 30 minutes, then thoroughly rinse.

3. Combine the palm sugar, salt and 1 cup water in a large pot and boil over high heat until the sugar carmelizes, 5 to 10 minutes.

4. Add the sweet potatoes, lower the heat to medium, and cook, stirring frequently, until the insides are the consistency of a baked potato, about 20 minutes.

5. Add the coconut cream, gently stir for 1 to 2 minutes, and then remove from the heat. The potatoes should be glistening in caramel.

6. Serve as dessert at any temperature.

*White limestone paste is used to stiffen the exterior of the potatoes for cooking, while leaving the inside soft and tender.

Recipe from Sokhita Sok, Cambodianow, Excerpted from The World Eats Here: Amazing Food and the Inspiring People Who Make It at New York's Queens Night Market, © 2020 by John Wang and Storm Garner. Photographs © John Taggart. Reprinted by permission of The Experiment. Available wherever books are sold. www.experimentpublishing.com

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/57/68570d82-5aa1-4790-b02e-ce6af27c81ac/queens_night_market_mobile_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/b5/5fb56b9e-3562-4a43-b862-edfd71592b10/queens_night_market_social_2.jpg)