The New Art Scene Transforming Santa Fe

The city’s image as a mecca of Southwestern-themed art and folksy spiritualism has begun to evolve, thanks to artists and entrepreneurs

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/32/54/3254aad4-196f-4a49-a912-b10e1052d394/istock-483990787.jpg)

This story originally appeared on Travel + Leisure.

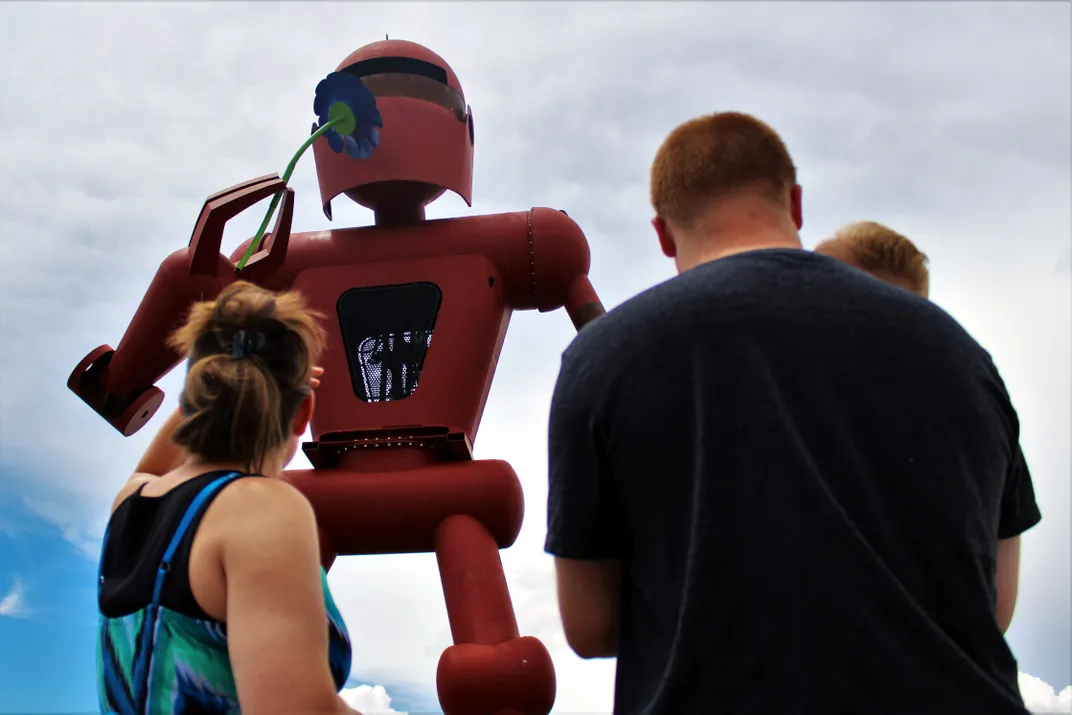

The House of Eternal Return, Santa Fe's unlikely new cultural destination, is a two-story Victorian built by the art collective Meow Wolf inside a converted old bowling alley owned by Game of Thrones author George R.R. Martin. The décor recalls the 1970s, with faux-wood paneling and afghan-covered beds and a hamster cage in a child’s bedroom. You follow various passageways—through the fireplace, the refrigerator, a closet—and find yourself in fantastical worlds that cling to the periphery of the house like moss. There’s a forest of neon trees. A Star Trek–ian spaceship. A mobile home plunked down in the middle of a desert.

The 22,000-square-foot installation is a haunted house without the monsters, an amusement park without the rides, an acid trip without the drugs. It is embedded with clues about the mysterious fate of a family who lived there. You can choose to simply steep yourself in the abstract visual stimuli, or you can attempt to piece the narrative together. In an upstairs office, I found the Perry Mason crowd: visitors of various ages pulling books from shelves, riffling through spiral notebooks, unpinning papers from a bulletin board, and clicking through files on a computer.

“It’s, like, a lot of Illuminati stuff,” Anna, a blond 16-year-old, said with teenage earnestness. She could have been discussing Dungeons & Dragons.

“It’s about the occult or time travel,” said her friend Sabrina, an 18-year-old with a pixie cut who was flipping through a legal pad like an extra in a crime show. The House of Eternal Return looks exactly like what it is: a surreal fantasia concocted by a group of 150 artists with a $2.7 million budget. Though it’s nothing like the soothing pastels and bright landscape paintings on display at Santa Fe’s many galleries and museums, visitors have flocked to it. In the six months after it opened in March, the exhibit brought in 350,000 visitors and revenue of $4 million.

**********

Santa Fe’s boosters like to say that more art is sold in Santa Fe than in any American city other than New York or Los Angeles—a surprising claim when you consider that the town’s population barely grazes 70,000. Collectors from all over the world travel to buy at its internationally renowned summer fairs: the Traditional Spanish Market, the Santa Fe Indian Market, and the International Folk Art Market. Santa Fe also has more than 200 galleries and a dozen museums. Much of the work is characterized by an overwhelming Southwesternness. One friend, an editor at the Santa Fe–based Outside magazine, summed it up as “burros with sunsets.”

More than a million tourists come each year in search of this Southwestern aesthetic. Santa Fe, a guidebook by longtime resident Buddy Mays that I picked up in the gift shop of the New Mexico History Museum, explains that the town’s quaint image was deliberately crafted as a means of driving tourism. Beginning around 1912, the year New Mexico was granted statehood, civic leaders sought to define Santa Fe’s architectural style, set restrictions on signage, and draw attention to Hispanic and Native American arts. The idea was to give the city a historic regional identity and the patina of an exotic travel destination.

The plan worked. Too well, some would argue. For years, Santa Fe has been trapped inside its own successful branding. Besides the art, there’s the ubiquitous turquoise jewelry and the inescapable red and green chiles. There’s the low-slung, mud-brown adobe architecture, the result of a strict zoning ordinance passed in 1957 that remains in effect today. There’s the pervasive undercurrent of New Age spiritualism.

Since the early 1980s, when an Esquire cover story called it “the right place to live” and a real estate boom brought a wave of second-homers and celebrities (Sam Shepard, Ali MacGraw, Jane Fonda, Val Kilmer), Santa Fe—or the idea of it, anyway—has been entrenched in the popular consciousness. Countless articles have praised its clean high- altitude air, tasteful old-world aesthetic, and quiet rhythms. Magazine spreads pay homage to “Santa Fe style,” a term (codified by a popular 1986 coffee-table book of the same name) that describes the town’s characteristic mix of Pueblo and Territorial Revival architecture and an interior-décor approach that favors folk crafts, Native American artifacts, and Western accents, like bleached steer skulls.

Many locals told me that they try to avoid their town’s most popular destinations, like the Plaza, the historic downtown square, and Canyon Road, the row of galleries that was once an artists’ enclave. Once in a while, they might go to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum to see the paintings that are so foundational to Santa Fe’s identity. But, my editor friend told me, “We’re due for a reset. It’s just been Georgia O’Keeffe straight through.”

**********

One could argue that Santa Fe has already gotten its reset in the form of Javier Gonzales, 50, the city’s first openly gay mayor. He was elected in 2014 after running on the slogan “Dare to grow young,” a reference to the town’s aging population (the median age is 44, seven years higher than the national average) and youth exodus (the under-45 population has sharply declined in the past decade).

On a bright, breezy day in early May, I met Gonzales at his office in city hall. Long-limbed and handsome in cowboy boots and jeans, he told me that Santa Fe “can’t be afraid to move forward” on issues that matter to people in their 20s and 30s: affordable housing, job growth in industries other than tourism and government, green energy, and nightlife. Gonzales plans to bring more film and digital media to town, not only to increase employment opportunities but also to diversify the cultural landscape, which leans disproportionately toward crafts and visual arts. He has challenged the city’s institutions to support creative work that is more inclusive, and “not just for the patrons,” as he put it.

I thought about this mandate at the opening of “Lowriders, Hoppers, and Hot Rods: Car Culture of Northern New Mexico,” on view until March at the New Mexico History Museum. Rather than the white, middle-aged crowd you might expect to see at an exhibition in the city’s most touristy district, the attendees were young, tattooed, and diverse. One was Julia Armijo, a seventh-generation Santa Fean who had come with her daughter, Justice Lovato, the founder and president of a local car club called Enchanted Expressions. Lowriders, Armijo told me, are works of art that are “built, not bought.”

Perhaps the best example of Santa Fe’s broadening definition of art is the ascent of Meow Wolf. The collective’s bowling-alley complex, which, in addition to the House of Eternal Return, contains studios, offices, and a youth-education center, is four miles across town from the Plaza, in the Siler Road District. The area, which was once dominated by auto-repair garages, metal shops, and old manufacturing buildings, has swiftly become a creative hub. Several small theater companies have sprung up: Teatro Paraguas, which performs in a black-box space; Wise Fool New Mexico, a nonprofit circus troupe; and Adobe Rose Theatre, which opened in January in a former door factory. The Arts and Creativity Center, a city-backed development providing live-work spaces for artists, could be completed there by next summer—a major step toward making Santa Fe, a town that depends on art, more hospitable to the people who create it.

Vince Kadlubek, Meow Wolf’s 34-year-old CEO, radiates the entrepreneurial savvy of Tim Ferriss and the monomaniacal intensity of Captain Ahab. As the collective’s chief fund raiser and spokesperson, he is superhumanly busy. At 9 a.m. on a Tuesday, he had not yet slept. Seated in a back room of Meow Wolf headquarters, Kadlubek, who grew up in Santa Fe—his parents are retired public-school teachers—expressed both pride and frustration in his hometown. “The cultural identity of Santa Fe was sooooo valuable, and powerful, and controlled, that it had very little ability to change, to be agile,” he told me. A decade ago, like so many young Santa Feans, he moved away—in his case, to Portland, Oregon—but he returned after a year. “I played this out in my head,” he recalled. “If Santa Fe keeps the same old identity, it becomes less and less attractive to a new generation. The demographic that is attracted to it grows older and older, and we just start to see the vibrancy—the actual health and sustainability—of the city that I grew up in and love start to come into question.” He pounded a fist on the table. “When I got back, I was like, ‘I’ve got to do something.’ ”

In 2008, he founded Meow Wolf with 11 other artists. In a former hair salon, the group hosted shows and punk-rock concerts while developing its signature creative style: immersive, colorful, multimedia, hyper-collaborative. Initially, Meow Wolf “had zero entry point into the art world of Santa Fe,” Kadlubek told me. But eventually the establishment took notice. In 2011, the Center for Contemporary Art commissioned the group to create the Due Return, an interactive 5,000-square-foot ship with a backstory about traveling through time and space to an alien planet. The project was a hit, and brought commissions for installations in Chicago, Miami, New York, and elsewhere.

Around the same time, Santa Fe resident George R.R. Martin, though a sexagenarian himself, had grown concerned about his town’s lack of youthful vigor. So in 2013, he purchased a dormant 128-seat, single-screen theater, the Jean Cocteau. On a spooky, windy night, I attended a showing of Blue Velvet. It was instantly clear to me that the theater also serves as a youth hangout. There are board games and a wall of books signed by authors, like Neil Gaiman and Junot Díaz, who have given readings. In addition to popcorn with real butter, the concession counter sells corn dogs, turkey Reubens, and deep-fried Twinkies. “Is George ever here?” I asked a girl with a half-shaved head. Yes, on Wednesdays for game night, she told me. “He really loves this place.”

When he opened the Jean Cocteau, Martin hired Kadlubek to oversee marketing. By then, Kadlubek had begun mapping out the permanent interactive-art experience that would become the House of Eternal Return. He found the abandoned bowling alley in 2014 and immediately e-mailed Martin. “Do you want to buy this building?” he asked. “We could do something cool with it.” As a fellow architect of fantastical worlds, Martin was intrigued. He purchased it for $800,000, spent $3 million more on renovations, and now rents it to Meow Wolf at a below-market rate.

“All these pieces came together,” Kadlubek said, leaning back in his chair. “This is the new identity. It’s still art. But it’s new art. And now we are the tourism darling of Santa Fe.”

As I drove back to the Plaza to meet the contemporary Native American artist Cannupa Hanska Luger at the gallery Blue Rain, it struck me that artists in Santa Fe are unusually aware of their city’s image. They seem to feel the need to decide whether to engage with or rebel against the local brand.

For Hanska Luger, 37, this dilemma is more personal because what many tourists want from Native American artists is art that looks Native American. “I try not to draw from my cultural background,” explained Hanska Luger, who was born on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota. He has long dark hair and a blank “To Do” list tattooed on his arm. Instead of his heritage, he told me, he draws from his experiences of popular culture: anime, cartoons, science fiction. But the inspiration for his eerily beautiful work—sculptures created out of yarn, felt, wood, and clay— also seems to come directly from his unconscious.

We climbed into his red pickup and drove to the Railyard District. A former warehouse precinct, it is home to galleries, restaurants, shops, a farmers’ market, and the independent Violet Crown Cinema. On our way, we passed SITE Santa Fe, the nonprofit contemporary-art center whose arrival in the Railyard District 21 years ago was the catalyst for the neighborhood’s transformation. Last summer, SITE Santa Fe broke ground for an ambitious yearlong expansion by New York City–based SHoP Architects that will add 15,000 square feet of space and a pleated metallic façade.

We met Hanska Luger’s friend and fellow artist Frank Buffalo Hyde, 42, at his studio. Buffalo Hyde told me that his cheeky acrylic paintings “deal with the commodification of popular culture and Native culture.” In one, a buffalo is sandwiched inside a burger bun—“a statement,” he said, “on how they’ve gone from the brink of extinction to being farmed as a healthy alternative meat.” Other paintings depict a Hopi woman dressed as a cheerleader and Gwen Stefani in an Indian headdress. Like Hanska Luger, Buffalo Hyde has felt the weight of the town’s aesthetic expectations. “For a long time,” Buffalo Hyde said, “the market dictated what Native art was, and if it wasn’t salable and marketable, it was just pushed aside.”

I asked what was salable and marketable. “Sunsets, coyotes, warriors on horses,” he said. “Anything non-threatening and decorative.”

**********

If Santa Fe has a culinary equivalent to the warrior on a horse or the burro with a sunset, it is the chile. Red, green, or Christmas-style—that means both mixed together—chiles are in or on almost everything. I’d been in Santa Fe 24 hours when I realized that every meal I’d eaten, including breakfast, had contained them. At Café Pasqual’s, the huevos rancheros arrived, soup-like, in a bowl atop black beans, covered in tomatillo and green-chile sauces. At Sazón, I’d had zuppa d’amour, a corn-poblano soup with amaretto cream, and a mezcal dusted with red-chile powder instead of salt. At Shake Foundation, I’d ordered the green-chile cheeseburger. I’d even taken an impromptu cooking class at the Santa Fe School of Cooking. The topic? Green-chile sauce. “I’ve always loved it,” said my lunch companion at Pasqual’s, an amiable woman who rides horses and works in PR. “But not everybody does.” She was quiet for a moment, then added, “You can get other things.

Edgar Beas, the new chef of the Anasazi Restaurant at my charming downtown hotel, the Rosewood Inn of the Anasazi, uses Southwestern ingredients whenever possible. But when it comes to the chile, his touch is light. One dinner began with focaccia made with onion ash, which renders the bread black, and butter sprinkled with the same oddly appealing ingredient. Next was a beet salad topped with scallops, oysters with (you knew it was coming) red-chile sauce, and tiny gnocchi accompanied by kumquats and crème fraîche. The main course was buttery seared halibut with potato polenta and squid ink, plus another dish of tamarind duck breast with local morels and green strawberries on a bed of barley. For dessert: a hazelnut gâteau accented with whiskey cream, prickly pear, a bay leaf, and ginger “snow.” The food was itself a form of contemporary Southwestern art.

Paper Dosa, one of Santa Fe’s most popular new restaurants, doesn’t perform any twist on Southwestern cuisine. Instead, it does South Indian food with an emphasis on fresh, seasonal, often surprising ingredients, like persimmons and sunchokes. Its specialty is the eponymous thin rice and- lentil crêpe that’s nearly as big as a boat sail. Married co-owners Nellie Tischler, a native Santa Fean, and Paulraj Karuppasamy, who was born and raised in India, met while working at Dosa, a restaurant in San Francisco, where they lived for a decade. Like Meow Wolf, Paper Dosa earned a following before finding a permanent home. The couple began with a series of well-attended pop-ups, then moved into an airy space south of the Railyard District in early 2015. Tischler showed me an iPhone photo of a line of customers snaking around the front of the restaurant. “That was yesterday,” she said.

When you taste the food, you understand why people wait. Many dishes are Karuppasamy’s family recipes, passed down by his grandmother. Tischler, a former drummer for Wise Fool who has bangs and a nose ring, sat with me as I enjoyed a plate of bright-red beet croquettes, a rich, nutty potato masala, and a complex asparagus soup with coconut milk and Thai chiles. “This food is what you would find in someone’s home in India,” she explained. We watched Karup pasamy, dressed in chef’s whites, cooking in Paper Dosa’s big open kitchen. “There are a lot of people in this town with a fresh energy, who left and came back.” Tischler said. “We got schooled in bigger cities and we’re doing what we learned, but in more interesting and inspiring ways.”

**********

After dinner one evening, I drove back across town to the Meow Wolf compound for one of their semi-regular parties. I was thrilled to have something to do. Santa Fe shuts down early, and I do not. When I’d ask residents about nightlife, they would seem slightly confused. You mean like a club? And then they’d recommend Skylight, the only one in town.

That there is so little to do at night has been an ongoing concern in Santa Fe. In 2010, a coalition of artists, promoters, and venues formed the After Hours Alliance to “identify creative ways to stimulate local nightlife,” as their mission statement puts it. In addition to bringing Uber to town, Mayor Gonzales has set up his own Nighttime Economy Task Force. These groups might seem silly, but the issue they’re attempting to confront is real: How do you keep young people from leaving town if nothing’s open late?

In the parking lot, I passed a “Kebab Caravan” food truck and a group of twentysomethings in thrift-store clothing. Inside, I wandered through the House of Eternal Return’s maze of psychedelic rooms until I reached an inner sanctum, where a DJ was performing on a dais. Electronic music pounded. Partygoers danced and twirled through a fog of dry ice. Someone whizzed past on roller skates. The room reeked of marijuana. It felt like anything was possible here, with Santa Fe’s graying elders asleep at home, and the next generation daring to be young.

**********

The Details: What to Do in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Hotels

Bishop’s Lodge A 1920s ranch turned resort and spa set on 317 acres in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The iconic establishment is currently undergoing a renovation and expansion and will reopen in spring 2018.

Drury Plaza Located in downtown Santa Fe, this spacious 182-room hotel opened in 2014 and has a pedestrian promenade that allows visitors to walk from Cathedral Park to the galleries on Canyon Road. Doubles from $170.

Four Seasons Rancho Encantado A secluded resort with 65 casita-style guest rooms, each with its own fireplace and terrace. The restaurant, Terra, serves excellent contemporary American cuisine. Doubles from $330.

Rosewood Inn of the Anasazi Just steps from Santa Fe’s historic Plaza, this 58-room hotel incorporates local handcrafted textiles and paintings into its design. Take in the traditional wood-beamed ceilings and three wood-burning fireplaces while sipping a margarita made with tequila from the property’s extensive collection. Doubles from $315.

Sunrise Springs Spa Resort Guests visiting this wellness resort can connect with nature via the property’s natural springs and 70 acres of gardens, walking trails, and undeveloped desert. Doubles from $280.

Restaurants & Cafés

Café Pasqual’s Locals and tourists line up out the door for the legendary Mexican and New Mexican cuisine. Entrées $26–$39.

Kakawa Chocolate House This charming chocolate shop, tucked in a small adobe house on the edge of downtown, serves all kinds of confections, but is best known for its chocolate elixirs.

Paper Dosa After earning a following with a series of pop-ups, chef Paulraj Karuppasamy and his wife, Nellie Tischler, opened this brick-and-mortar spot, where they serve South Indian cuisine and their eponymous specialty, a thin crêpe made from a fermented rice-and-lentil batter. Entrées $10–$18.

Sazón Chef Fernando Olea focuses his small menu on daily specials made with locally sourced produce and meat accompanied by a medley of moles. Entrées $27–$45.

Shake Foundation This tiny, walk-up burger joint is dedicated to the preservation of the green-chile cheeseburger, and that’s precisely what people come for. But the fried-oyster and spicy fried-chicken sandwiches are also worth a try. Burgers $4–$8.

Activities

Blue Rain This 23-year-old gallery shows fine contem-porary Native American and regional art in a variety of media: painting, ceramics, bronze, glass, wood, and jewelry.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum With more than 3,000 pieces dating from 1901 to 1984, it’s the largest permanent collection of O’Keeffe’s work in the world. It was the first museum in the United States dedicated to a female artist.

The House of Eternal Return This colorful, 22,000-square-foot, immersive multimedia art installation, created by the collective Meow Wolf, is the stuff of childhood imaginations. It is housed in an erstwhile bowling alley owned by Game of Thrones author George R.R. Martin.

Jean Cocteau Cinema Before acquiring the bowling alley, Martin bought and restored this 128-seat, single-screen theater. It shows old, independent, and cult-classic movies, and hosts a weekly game night, which Martin is rumored to attend.

New Mexico History Museum This enormous exhibition space, next to the 400-year-old Palace of the Governors, has collections covering various aspects of New Mexican history.

SITE Santa Fe Founded in 1995, this contemporary art space has become known for its international biennial exhibition. The current iteration, “Much Wider Than a Line,” on display until January 2017, is the second installment in SITE’s series that focuses on art from the Americas.

Violet Crown Cinema The year-old, 11-screen theater in the Railyard District shows new releases, classics, independent, foreign, and art-house films. It also has a full bar and a café that serves farm-to-table food that can be enjoyed while watching your favorite flick.

Other articles from Travel + Leisure:

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.