Savoring Puebla

Mexico’s “City of Angels” is home to gilded churches, artistic treasures and a delectable culinary culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Puebla-Mexico-631.jpg)

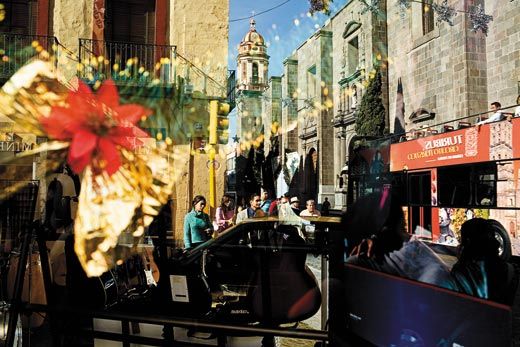

Despite (or because of) its monumental scale, its crowded, buzzing intensity, its archaeological and political importance, Mexico City's zócalo, or central square, is—for all its beauty and grandeur—not the sort of place where most of us would choose to hang out: eating lunch, meeting friends, watching people go by. But a two-hour drive southeast from the capital, Puebla has at its heart a gorgeous historical center, a hundred-block showplace of Colonial and Baroque architecture. And its handsome zócalo is the gentle heart of that heart. Pause for a few moments on one of its wrought-iron benches, and you think you could stay there forever.

Lined with shady trees and cool walkways surrounding an elaborate 18th-century fountain that features a statue of the Archangel Saint Michael, the region's patron saint, the zócalo, also known as the Plaza de Armas, is endlessly entertaining. Everything seems emblematic of the ingenious ways in which present and past coexist and harmonize in this historic and modern city, home to over a million people. An old man dressed in the headdress and robes of a Mesoamerican shaman plays a flute and dances near a vendor holding a bouquet of giant balloons bearing the sunny face of SpongeBob SquarePants. Under a tent, workers inform passersby about the demands of the laborers at one of Mexico's multinational factories, while, in a distant corner, a film crew is shooting a commercial for mobile phones. A quartet of 21st-century mariachis—young men in sunglasses, jeans and T-shirts—are practicing Beatles songs, while a pair of tiny twins chase pigeons until their parents warn them to watch out for their older sister's snowy Communion dress. In the arched porticoes surrounding the square are bookstores and shops selling stylish clothes and devotional objects, as well as restaurants and cafés at which you can spend hours, sipping coffee and nibbling churros, the fried crullers that may be Spain's most uncomplicatedly beneficial export to the New World.

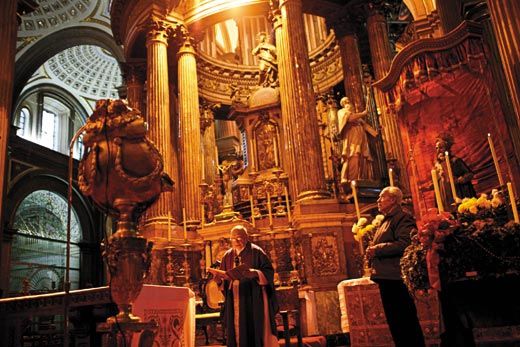

Without leaving the confines of the zócalo, you can contemplate the facade of the city's impressive and somewhat intimidating Town Hall, and, more rewarding still, the exterior of the cathedral of Puebla, a masterpiece of Mexican ecclesiastical architecture. The building was begun in 1575 and consecrated in 1649, but the interior—decorated with carved and inlaid choir stalls, onyx statuary, immense painted altars and a gargantuan pipe organ—required several hundred more years to complete; the exuberant canopy over the central altar was finished in 1819, and changes continued to be made into the 20th century. As a consequence, the church functions as a kind of guided tour through the major styles and periods of Mexican religious architecture—Colonial, Baroque, Mannerist and neo-Classical, all assembled under one soaring cupola.

Hearing the carillon chime every day at noon in the cathedral's south tower, reputed to be the tallest in Mexico, you can almost believe the legend that the daunting engineering problem of how to install the 8.5-ton bell in the unusually high tower was miraculously solved when angels took over to help the builders. Overnight, it is said,the angels raised the bell and set it in the tower.

Indeed, angels play a major role in the religious history of Puebla, which was founded in 1531. According to one story, the city owes its location and its very existence to a dream of Fray Julián Garcés, the first bishop of Puebla, who was appointed by Pope Clement VII in 1525, four years after Hernando Cortés brought about the fall of the Aztec Empire. In the Dominican friar's vision, angels showed him exactly where the city should be constructed.

The angels were not only blessedly helpful but astonishingly professional, coming equipped with string lines and surveying tools that situated the settlement, demarcated its boundaries and laid out a grid of streets designed to reflect the latest European notions of orderly urban planning. Puebla de los Angeles (City of the Angels) the town would be called. Occupying a lush valley in the shadow of a volcano, Popocatépetl, it would prove a pleasant place for the Spanish colonizers to live among the area's indigenous tribes (whose numbers had already been ravaged by the disease and bloodshed that followed the conquest) and beneath the bishop's angelic guides, fluttering beneficently over the churches that the friars and governors would build for themselves, their communities and the newly converted locals.

A less romantic explanation for the establishment of Puebla involves the colonial leaders' search for an area that would allow the settlers to own property and farm the land with a degree of success that might blunt the edge of their longing for their former lives in the Old World. Largely uninhabited, covered with a layer of fertile soil, blessed with a hospitable climate year-round, and positioned to be a convenient stopover on the route from the port of Veracruz to the Mexican capital, the spot on which Puebla would be built seemed the ideal place to realize the dream (somewhat more earthbound than Fray Garcés') of a prosperous industrial, agricultural and spiritual center that would serve as a model for others throughout New Spain. In addition, the new town would be located near the indigenous population center—and labor pool—of Cholula.

In the area immediately surrounding Puebla's zócalo, there's abundant evidence of the essential role played by one of the city's most important leaders, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, who arrived to serve as bishop of Puebla in 1640, and, two years later, as the region's viceroy as well. Eager to see the cathedral completed, Palafox paid its building costs partly from his own pocket and presided over its consecration. In his nine years as bishop, Palafox oversaw the construction of a seminary, two colleges and 50 churches. But the true key to Palafox's character (the illegitimate son of an aristocrat, he was a reformer zealous enough to make his political superiors uneasy) can be found in the library he amassed, which can still be visited, directly across the street from the back entrance to the cathedral.

With its arched and vaulted ceiling, scalloped Baroque windows, tiered balconies, gilded altar, carved-and-polished wooden bookcases and huge, ancient volumes made of vellum, the Biblioteca Palafoxiana suggests a real-life version of Harry Potter's library of magic spells. The soaring space is moving as well as beautiful; it evokes all the reverence and hunger for learning, for books, and what books can contain, that inspired the most high-minded of the colonial settlers to introduce the best aspects of the Renaissance to the New World. The library's elegance and power trump whatever qualms one might have about admiring the culture that an occupying country imposed on the colonized, whose own culture was underrepresented in the 50,000 volumes on Bishop Palafox's shelves. Ultimately, entering the hushed and stately institution reminds you of all the ways in which libraries, especially beautiful libraries, can be as transporting and spiritual as cathedrals.

Like the rest of Mexico, Puebla has had a troubled history marked by war, invasions and revolutions. Several important military confrontations took place there, most famously the Battle of the Fifth of May, Cinco de Mayo, commemorated in a holiday that has assumed great significance for Mexicans living outside their own country. At the battle, which occurred not far from Puebla's center, on May 5, 1862, the Mexican Army defeated the French with the aid of local troops. Unfortunately, the French returned a year later and smashed the Mexican forces and occupied Mexico until they were defeated by Benito Juárez in 1867.

Puebla's aristocratic upper class, which still maintains familial and cultural connections to Spain, lives side by side with a rapidly growing middle class, while many of the city's desperately poor residents inhabit its sprawling, ever-expanding margins. The capital of Mexico's Puebla state, the city is widely regarded as politically conservative and religious, its people deeply tied to tradition and to the church.

Perhaps coincidentally, Puebla is home to several of the marvels of Mexican Catholicism—not only the massive cathedral, but also the Rosario Chapel, located to the left of the central altar in the Church of Santo Domingo. Described by a visitor in 1690 as the "Eighth Wonder of the World," the chapel is so thickly decorated—so heavily populated with statues of angels, saints and virgin martyrs and figures symbolizing faith, hope and charity—and, above all, so artfully and generously splashed with gold that to stand beneath its dome is not just metaphorically, but quite literally, dazzling. The density of detail and form is so over-the-top that you can only experience it a little at a time, so that photographs (no flash, please) are useful reminders that the gilded splendor could in fact have been as ornate and exuberant as you recall.

Aside from the governors and priests who worked to establish and maintain control of the city, the most influential of the early Spanish immigrants to Puebla were a deceptively humble delegation of potters and ceramicists from the Spanish town of Talavera de la Reina. Even as the politicians and friars labored to govern Puebla's civic and spiritual life, these brilliant craftsmen addressed themselves to its vibrant, glittering surface.

Enthusiasts of tile and tile-covered-buildings (I'm one of them) will be as blissful in Puebla as in Lisbon or southern Spain. The streets of the downtown area are lively, but not so crowded or pressured that you can't stop and gaze up at the sunlight bouncing off ceramic patterns of clay colored blue, brown and Nile green, or at the figures (wicked caricatures of the enemies of the home's original owner) baked into the exterior of the 17th-century Casa de los Muñecos. The effect can suggest elements of Moorish, Aztec and Art Nouveau styles. The nearer one gets to the zócalo, the better maintained the buildings are, but farther out, where the tiled facades are more frequently hidden behind electronics stores, taco stands, the studios of wedding and graduation photographers and outposts of OXXO, the Mexican equivalent of 7-Eleven, the dwellings take on a slightly crumbling melancholy.

A lighthearted, carefree, almost reckless enthusiasm informs the decoration of many of these structures, in which the hand of the individual craftsman (or artist, depending on your point of view) is everywhere in evidence. The name of the Casa del Alfeñique, a beautiful 18th-century building that houses a museum of the history of the region, translates roughly as the "house of the egg-white confection," something resembling meringue.

In 1987, Unesco designated Puebla a World Heritage site, noting that the city contains approximately 2,600 historic buildings. It would be easy to spend weeks in the central historic district, taking time for each lovingly preserved colonial wooden door, each plaster angel, each curlicue and trellis, each vaulted courtyard leading to a shaded patio—a hidden oasis just a few steps off the sunny street. The sheer variety of food shops—from open-air fish stalls to ice-cream parlors where you can sample avocado, chile and other unexpected flavors—reminds you of what it was like to inhabit a highly functioning but pre-corporate metropolis, before so much of urban life was blighted either by the middle-class flight from the inner city, or, alternately, by the sort of gentrification that has given so many streetscapes the predictability and sameness of a high-end mall.

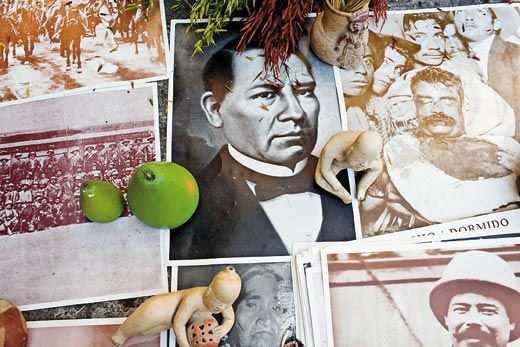

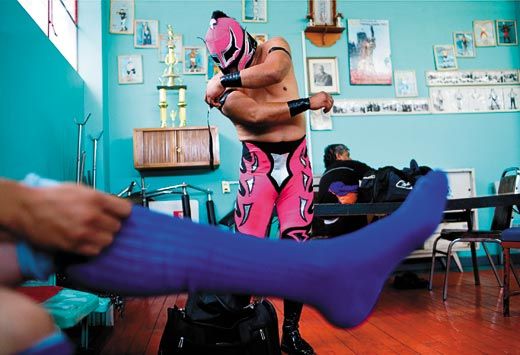

Likewise, Puebla reminds you that cities can still be centers of communal as well as commercial life. Proud of their town, of its history and its individuality, its residents see their home as a place to be enjoyed, not merely as a hub in which to work and make money. There's a broad span of cultural activities—from concerts at the stately 18th-century Teatro Principal to the Monday-night Lucha Libre fights at the main arena, where masked wrestlers throw one another around before a roaring crowd. On weekends, Poblano families stroll through the flea market in the pleasant Plazuela de los Sapos, where vendors sell goods ranging from old jewelry, religious pictures and vintage postcards to purses woven from candy wrappers and belts made from beer-can tops.

At the top of the Plazuela de los Sapos is one of Puebla's most beloved institutions, the charming La Pasita, manufacturer of the eponymous sweet, walnut-brown liqueur, tasting of raisins, made from local fruit and known throughout Mexico. A tiny, stand-up bar with only a few seats, La Pasita also sells a selection of other dessertlike but surprisingly powerful drinks, flavored with coconut, ginger or anise, and served in shot glasses together with wedges of cheese. Founded in 1916, the store is open only for a few hours in the afternoon, and it's a temptation to spend those hours getting sweetly looped and finding yourself increasingly interested in La Pasita's unique décor, the shelves covered with bric-a-brac from all over the world—images of movie stars and historical figures, toys and playing cards. A poster of a young woman reads "Pasita calmó su pena" ("Pasita calmed her sorrow"), and you can't help thinking that, over the course of almost a century, this delightful bar has helped its customers do exactly that.

For travelers who want to spend at least some of their time in Puebla doing something beside relaxing in the zócalo, exclaiming over the extravagantly tiled buildings, visiting churches and drinking candylike liqueur, the city offers a wide variety of museums.

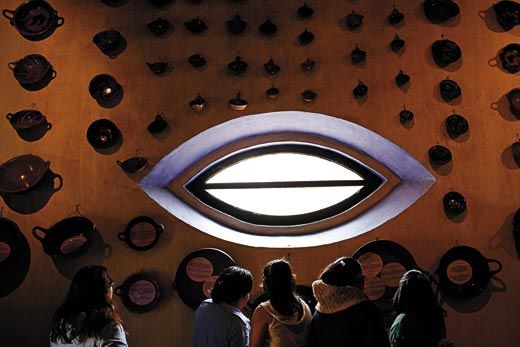

Opened in 1991, the elegantly designed Museo Amparo occupies two Colonial buildings combined to display an extraordinary private collection of pre-Columbian and Colonial art. It's one of those gemlike museums (Houston's Menil Collection comes to mind) in which every object seems to have been carefully and consciously selected with an eye for its uniqueness and aesthetic perfection, so that even visitors who imagine that they are familiar with the wonders of Mesoamerican culture will find themselves catching their breath as they move from one dramatically lit gallery to another, past vitrines displaying artifacts that include a sensitively rendered Olmec figure reminiscent of Rodin's Thinker, expressive stone masks, realistic sculptures of animals (a dog with an ear of corn in its mouth is especially striking) and others that could almost persuade you of the existence of the most fanciful and unlikely creatures, as well as all manner of objects relating to rituals, games, mythology and scientific and astrological calculation.

If I had to choose just one museum to visit in Puebla, it would be the Amparo, but with just a bit more time, I'd reserve some for the former convents of Santa Monica and Santa Rosa, not far from each other, and both an easy walk from the zócalo. Built in the early 17th century to surround one of the loveliest tiled courtyards in a city of gorgeous courtyards, the museum in the former convent of Santa Monica illuminates the cloistered existence of Mexican nuns—most notably in the decades that began in the mid-19th century, when the government officially banned monasteries and convents, forcing monks and nuns to continue living there in secret. In the dark maze of narrow corridors, hidden chapels, a spiral staircase leading down into subterranean chambers and almost shockingly spare cells, it seems possible to inhale the atmosphere of secrecy and seclusion that the sisters breathed. A collection of (I suppose one could say) jewelry designed for self-mortification—belts studded with nails, bracelets fashioned from barbed wire—testifies to the extremes of penance that these devout women practiced. Yet elsewhere throughout the museum are abundant examples of the fantastic inventiveness and creativity that the women poured into the lace, embroidery and religious objects that they fashioned to fill the long hours of their contemplative lives.

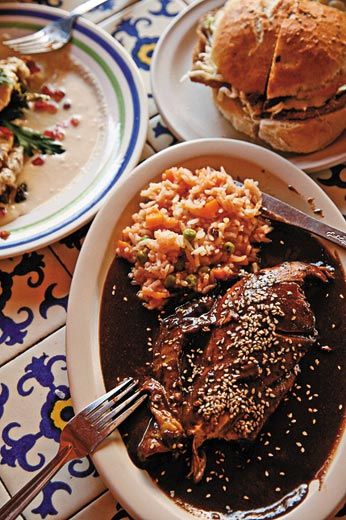

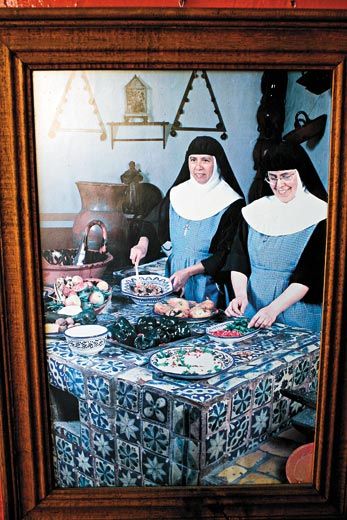

Things are a bit brighter and more cheerful at the former convent of Santa Rosa, where the finest examples of Mexican crafts—pottery, masks, costumes, paper cutouts (including one of a slightly demonic Donald Duck), painted carousel animals and so forth—have been gathered from all over the country. My favorite section features a group of wooden armatures designed to launch displays of fireworks that, when lit, trace the fiery outlines of an elephant or a squirrel. But the museum is rightfully proudest of the former convent's kitchen. The glorious cocina is not only one of the city's best examples of Talavera tilework but, according to popular legend, the place where the resourceful nuns coped with the stressful prospect of a surprise visit from the bishop by combining the ingredients on hand and in the process invented the richly spicy, chocolate-infused, sesame-inflected sauce—mole poblano—that is now the region's most well-known dish.

The mention of mole poblano brings up yet another—and one of the most compelling—reasons to visit Puebla: its food. I've heard the city described as the Lyon of Mexico, and while it may be true that its cooking is the best in all of Mexico (as Poblanos claim), the comparison to Lyon would hold only if the five-star restaurants of the French culinary capital reconstituted themselves as open-air stands selling foie gras cooked over hot plates or charcoal braziers. There are good restaurants in Puebla, and it's useful to seek one out if you are there in summer, when it's possible to sample Puebla's second most famous contribution to its country's cuisine, chiles en nogada, peppers stuffed with meat and fruit, covered with a creamy walnut sauce and dotted with pomegranate seeds, so that its red, white and green colors are said to patriotically evoke those of the Mexican flag.

But in most cases, it is widely agreed, street food trumps fine dining. Generally speaking, the most reliable ways to find the best food are, first, to follow your nose, and second, to fall into place at the end of the longest line.

Several of these lines can be found every day at lunchtime a block or two west of the Biblioteca Palafoxiana, where Poblanos queue up for molotes, deep-fried turnovers made from corn tortillas stuffed with a choice of cheese, tinga (a mixture of shredded meat, chiles, tomatoes, onions and spices), sausage, and, in season, the delicious huitlacoches, or corn fungus. Throughout the city are small places specializing in cemitas, overstuffed sandwiches constructed on grilled, split sesame rolls, and tacos arabes, wheat tortillas filled with meat carved from a turning rotisserie column; both of these hearty snacks may have borrowed their names from the waves of Lebanese immigrants (cemitas may be related to the word for Semite) who arrived in Mexico beginning in the 1880s.

But by far my favorite destination for a Puebla night out is the Feria del Carmen, which takes place every July in the Jardin del Carmen, a few blocks from the zócalo along the Avenue 16 de Septiembre. The fair, which commemorates the feast day of Our Lady of Carmen, is an old-fashioned carnival of the sort you hardly see anymore north of the border, funkier and more earthy than anything you're likely to find at the most authentic, old-school county fair. If you're brave and trusting enough, you can ride a creaky Ferris wheel or let yourself be spun vertiginously in a scarily vintage whirligig, and, if you have a strong stomach, you can visit one of the forlorn sideshows.

But the major attraction of the feria—what draws Poblanos here—is the food. Under strings of bright-colored lights, women tend huge circular grills on which chalupas poblanas (mini-tortillas topped with red or green salsa) sizzle. A family sells plastic foam cups of esquites—corn kernels spiced with chile powder and other pungent Mexican herbs, then sprinkled with lime juice and cheese. When you tire of navigating the crowds and waiting in line to be served, you can sit at a table under a tent and have the proprietor bring you plates of huaraches (handmade tortillas stuffed with steak that resemble—in shape, and occasionally, in durability—the sandals after which they're named) or pambazos, fried bread filled with meat and topped with lettuce, cream and salsa.

Everything is so attractive and delicious, and it's all so much fun, it's hard to admit to yourself that you've reached the saturation point. Fortunately, you can walk off some of that sufficiency on the way back to the zócalo, where you can rest, watch people pass by, listen to the roving street musicians and enjoy all the sights and sounds of a balmy evening in Puebla.

Francine Prose's most recent book is Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife.

Landon Nordeman previously photographed Elvis impersonators for Smithsonian.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.