12 Secrets of the New York Subway

History runs deep in the legendary transit system

:focal(1599x719:1600x720)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/7e/f37ef22b-c4c5-4e85-84b1-39638846a1f0/42-16438517.jpg)

The heart of New York City may be Times Square, but its lifeblood is its subways. Comprised of more than 600 miles worth of mainline track, New York's intricate transportation system whisks an estimated 5.6 million commuters across the five boroughs every weekday.

The iconic subway wasn’t always the mammoth operation it is now. Opened in 1904, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) was one of several privately owned subway companies, including the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT) and the Independent Subway System (IND). The systems eventually merged to form today's Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA).

These days, the subway system’s legacy runs as deep as the subterranean tracks themselves—and plenty of pieces of little-known history date back to before today's subway even existed. Here are 12 subway secrets you should know:

You can tour an abandoned subway station.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/2a/d12ab46b-ddd8-4d19-890a-effc9048eb8e/5159191290_9c4c45e360_b.jpg)

Several times each year, the New York Transit Museum takes a lucky group of people on a tour of a shuttered subway station in Lower Manhattan. Opened in 1904, the City Hall stop on the 6 train has been closed since 1945, but its immaculate arches, electric chandeliers, and detailed tile work remain intact. “It’s a very small station [compared to the more modern ones],” Polly Desjarlais, an education assistant at the museum, tells Smithsonian.com. “Over time, the curved platform became too short to accommodate newer trains.”

If you want to take a tour of the station, there’s a catch: You must become a member of the museum, pass a background check and patiently wait for a slot to open. Alternatively, you can ride the 6 train downtown (southbound). Stay onboard as it loops through the City Hall station and makes its way north—you may glimpse the station through the window. Untapped Cities also offers tours of the subway system's abandoned remnants.

When subway cars retire, they become underwater habitats for sea life.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/31/99/31992500-30d8-4a66-affb-17f62434e295/42-20705014.jpg)

Rather than send decommissioned subway cars to their rusty grave in a landfill, the MTA sank 2,500 of them into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean between 2001 and 2010 as part of a program to build artificial reefs. In the time since, these underwater habitats off the coasts of New Jersey, Delaware, and other states along the eastern seaboard have become home to numerous sea creatures. A program official tells CNN that the subway reefs now contain 400 more fish food per square foot than the ocean floor.

There’s a subway station filled with more than 130 bronze sculptures.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/24/662449a9-2a67-4eb3-b660-0b9b2e9b9b35/8678594727_bfc5792790_k.jpg)

For years, the MTA has commissioned local artists to create artwork for its more than 450 subway stations as part of its Arts for Transit program. But by far one of the quirkiest commissions is by artist Tom Otterness, who, beginning in the 1990s, created more than 130 bronze sculptures for the 14th Street/Eighth Avenue station. Called “Life Underground,” the collection touches on class and money, and includes an alligator popping out of a manhole cover, an elephant and characters clutching bags of money and subway tokens. Otterness continued adding pieces until 2004, making about five times more sculptures than the original commission requested. “I just got so excited I donated more and more work to the system, and in my view nothing didn’t fit, everything seemed to have a place,” he said in an interview with The New York Daily News.

The city’s first subway ran on pneumatic power.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/da/4bdac0cf-8854-4695-afc4-caf1041378d0/beach_pneumatic_plan.jpg)

In 1870, inventor Alfred Ely Beach debuted what he called the Beach Pneumatic Transit, the city’s first underground mode of transportation. Stretching 300 feet (about one city block) from Warren Street to Broadway in Lower Manhattan, the single-track line ran on pneumatic power. The system worked by using compressed air and water pressure to propel a single train car forward. Beach built the track in secret as a sneaky way to demonstrate the power of pneumatic tubes. Although it was only operational until 1873 (and was merely a demonstration), the technology he championed is still used today as a delivery system that pushes mail from one part of a building to another.

If laid end to end, the subway system’s tracks would stretch from NYC to Chicago.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5f/2d/5f2d4429-9b47-4c9b-b9a7-bdb38d9e7c61/10103423155_a78b8c4757_k.jpg)

In total, the subway system is comprised of 660.75 miles worth of mainline track. But when you include track used for non-revenue purposes, such as the subway yards where the trains are stored, the total swells to more than 840 miles. That’s about the distance from NYC to just outside of Milwaukee—one long subway ride.

A 16-year-old hijacked a train in 1993 and took it for a joyride.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cd/43/cd4304df-f76a-4934-ace8-df594bd9ddf0/01576093468.jpg)

A 16-year-old named Keron Thomas made motorman history in 1993 when he took an A train on a forbidden ride throughout the city for more than three hours. Thomas planned the stunt for months, and the teenager studied MTA manuals on subway train operations before his urban expedition. Fortunately, no one was hurt during Thomas’ illegal stunt. He was arrested and charged with reckless endangerment, criminal impersonation and forgery and walked away with a nickname: “A Train.”

The MTA ran a “Miss Subways” beauty pageant for more than 30 years.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2a/c2/2ac26fce-efc7-4fa8-8fba-fb04a41f42e1/8232723619_1407defd14_h.jpg)

The subway is one of the last places you would expect to find a beauty pageant, but from 1941 through 1976, the MTA hosted just that, advertising its “Miss Subways” in subway cars and stations. “The idea began [with] an advertising company to draw people’s attention to ads,” Desjarlais says. The idea worked and the pageant became a popular competition for women living in the five boroughs. In 2014, to coincide with the NYC subway’s centennial, the MTA resurrected the pageant. The winner: 30-year-old dancer Megan Fairchild who, upon winning, mingled with Ruth Lippman, the title holder for 1945.

Commuters once found creative ways to steal subway rides.

Before there were MetroCards, travelers paid for rides using subway tokens. But some scofflaws found ways to ride for free. One popular method was sucking tokens out of turnstiles. Here’s how it worked: The thief would lodge a gum wrapper or piece of paper into the slot and wait for an unknowing passenger to plunk down a token. When it didn’t take, the thief would return to the turnstile and suck the jammed token out with her mouth, often swallowing or choking on it in the process.

Cheapskates also snagged rides with tokens from the Connecticut Turnpike, which were the same shape and size as the ones used by the MTA but cost 57 cents less than the MTA’s 75-cent tokens in the 1980s. After years of stalemate with Connecticut in what was dubbed “The Great Token War,” both transit authorities worked out a deal: The MTA would collect the tokens, which often totaled in the millions, and return them to Connecticut for a reimbursement of 17.5 cents each.

During the holidays, riders can travel on vintage Nostalgia Trains.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/6f/d16fb4d1-47aa-4dc9-9af9-204c6ed5f755/8879614239_dd2b17a8d6_k.jpg)

Every weekend from Thanksgiving to Christmas, the MTA dusts off a fleet of vintage subway cars and sends them down the track as part of the Nostalgia Train program. Equipped with ceiling fans, rattan seats and vintage advertisements, the subway cars date back to the 1930s and offer a whimsical ride on the N line for anyone who wants to go back in time. “Sometimes the MTA will run the vintage trains in the summer to Coney Island, or to Yankee Stadium [in the Bronx] for the season opener,” Desjarlais says. “You just have to be lucky enough to be there when it arrives in a station; all it costs is a [$2.75] MetroCard swipe.”

A Nobel Prize-winning scientist used a subway station as his lab.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/ed/deed2f37-c14e-4fbf-8062-943bf180c9c5/pl3479.jpg)

In 1936, Austrian scientist Victor Hess received a Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of cosmic radiation. After immigrating to the United States during World War II, the Fordham University professor continued conducting radioactive experiments while living in New York. His lab of choice: the subway. Using the 191st Street station in Washington Heights, the deepest station in the system, he measured the radioactivity of the granite that sat between Fort Tyron Park and the station 180 feet below.

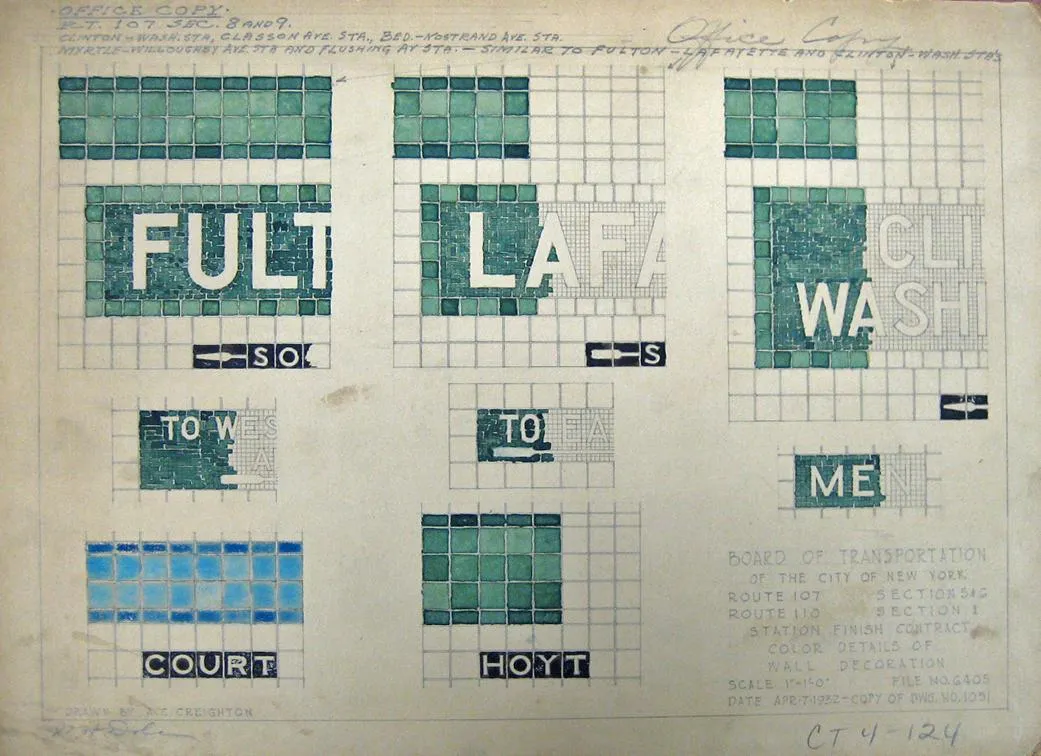

Subway tiles were color-coded to help commuters determine their location.

As a way to help riders navigate, the IND subway company adopted a color-coded system. The idea was that the subway tiles could tell riders whether they had reached a local or express stop. The system never caught on, but riders can still see remnants of it in certain stations like the Lafayette Avenue and Fulton Street stops, which are marked with light green tiles. “It was supposed to be informational and useful for passengers, but I don’t think it was well advertised by the company,” Desjarlais says. “I often conduct subway tours, and I’ll meet people who were alive back then and they didn’t even know about it.”

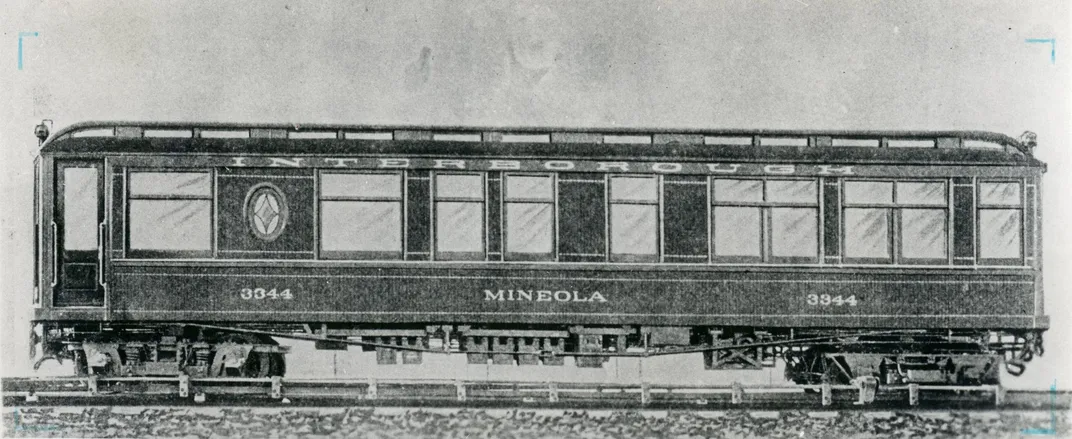

The owner of the IRT company had his own private subway car.

Rather than travel with other mere mortals, August Belmont, Jr., the owner of the IRT company, rode in style in his own private subway car. Decked out with a bathroom, kitchen, a wooden desk and other opulent touches, the car was called the “Mineola” and used to entertain Belmont's out-of-town guests. Today it’s on display at The Shore Line Trolley Museum in East Haven, Connecticut.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.