Seven Planned Utopian Towns That You Can Visit Today

These utopic cities—some working, some not—can still be visited today

:focal(1341x685:1342x686)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1c/8f/1c8f07a0-dedf-4895-b461-cfdfb142d718/auroville-1.jpg)

Throughout history, people have been in search of the perfect town. A utopia, built with harmony in mind, where everyone gets along and works together without conflict. Thomas More coined the term in 1516 with his book, Utopia, where he describes a perfect yet fictitious island society’s ways of life. Since then, humans have tried to replicate this society, not just in stories but also in real life. A handful of towns have sprung up around the world designed with this ideal society in mind. Though inevitably they fall short of perfection, it’s still possible to visit some of these towns and cities that were once (and may still be) a bastion of good will and cooperation.

Auroville, India

Ask anyone in Auroville who started the town, and residents will tell you it was the Mother—a woman who dreamed of a unique city where nothing is owned by anyone and everyone lives in peace and harmony without politics, religion or nationality. And they’d be right. In 1968, a woman named Mira Alfassa (the Mother herself) defined Auroville’s charter—noting “Auroville belongs to nobody in particular. Auroville belongs to humanity as a whole. Auroville wants to be the bridge between the past and the future”—and thus opened the town for residents. Auroville is designed after a galaxy, surrounding a banyan tree in the geographical center and a gold-plated sphere full of meditation rooms that took 37 years to build. Everything in the town is owned by the Auroville Foundation, which is owned by India’s government.

Some 50 years later, Auroville is now funded by tourism dollars from people looking to get a piece of peace, as well as more than 2,000 residents from about 40 countries. A number of small businesses have popped up, selling handmade items like paper and incense, and the proceeds benefit the town. There are few buildings save for some homes, a school, a town hall, farms, restaurants and the meditation sphere. No one uses cash; instead, Auroville runs on "aurocards," something similar to a debit card. Healthcare, electricity and school are all free, and residents handle maintenance in the town.

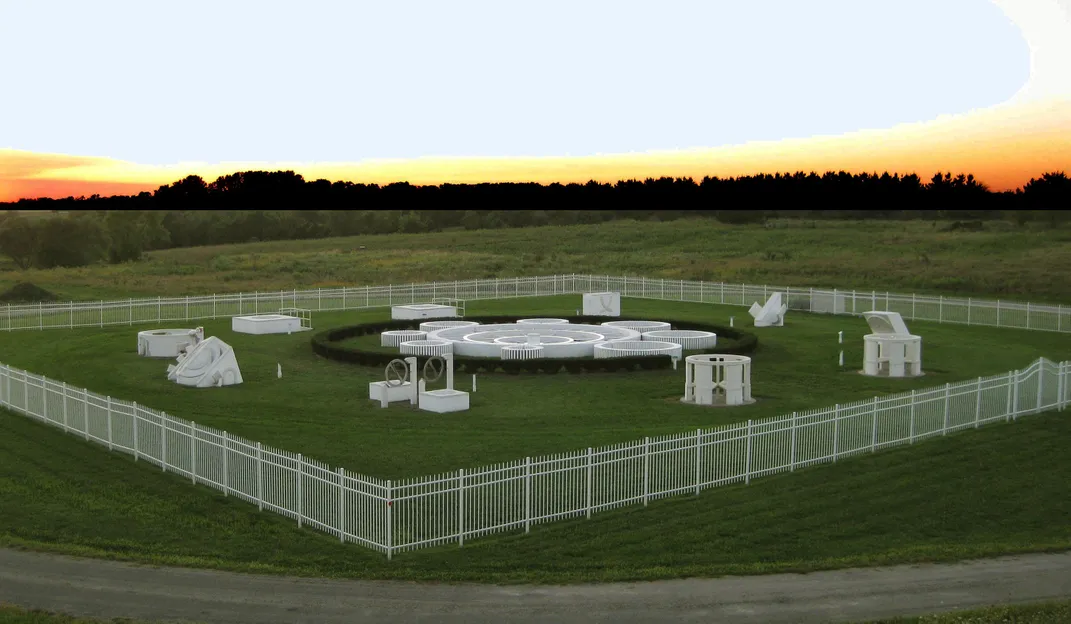

Maharishi Vedic City, Iowa

This one-square-mile city in Iowa, incorporated in 2001, is the only city in the country officially built on the principles of transcendental meditation. The practice has been going strong since the Beatles introduced it to the wider world in the 1960s by following transcendental meditation’s founder, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. The foundation of Maharishi Vedic City is Veda, an ancient Hindu principle that prioritizes harmony, balance and natural law. A group of transcendental meditation followers founded the town, and now a five-person council acts as the city's government. Every home is designed the same way, to promote those tenets and follow the path of the sun, all facing east with a golden roof ornament, a fence surrounding the property and a central space in the house meant for silence. Each building is arranged on one of ten circles in a large constructed ring. There’s an open-air observatory built from sundials and designed to replicate the structure of the universe in miniature, a hotel, a spa and public schools that teach children the ways of transcendental meditation in twice-daily sessions in addition to regular schoolwork.

Since its inception, synthetic pesticides, fertilizers and non-organic food have been completely banned. In their place, there’s a large organic farming business that distributes to nationwide chains. Renewable energy powers the city, and residents come together twice daily (as possible) to practice transcendental meditation.

Arcosanti, Arizona

When it opened in 1970, Arcosanti’s founder, Italian architect Paolo Soleri, imagined the small Arizona desert complex would evolve into a city of thousands of people, all living together in harmony in what he called an arcology—a community where nature and architecture work together to create a harmonious existence. The goal was to bring everyone together in a complex that both limited damage to the earth and also allowed everyone to feel happy and fulfilled. Since that time, more than 8,000 volunteers and a handful of full-time residents have built the community to what it is today: a collection of aged mixed-use buildings and public spaces that are only a fraction of what Soleri envisioned—a practical test of the theoretical arcology concept that draws students of architecture and free spirits looking to commune with nature.

Today, Arcosanti survives on people coming for multi-month workshops to help with daily activities at the complex, an ongoing production of ceramics and bronze windbells, tourism and events. The community remains a construction site (the design is only about 3 percent complete), run by the nonprofit Cosanti Foundation.

Royal Saltworks of Arc-et-Senans, France

Though an industrial complex, the Royal Saltworks of Arc-et-Senans was designed to be a utopia nonetheless, a place of life, work and worship for employees of the facility and their families. The complex’s original design, imagined by architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, comprised a large circle of buildings with salt production facilities in the center. Ledoux was known for creating utopian designs that supported human activities and interaction, though many were never constructed. Salt production at the site began in 1779 and continued until production officially stopped in 1962. While it was in use, it was far from the utopia Ledoux planned. Workers struggled under harsh conditions and the communal housing reportedly aggravated personal conflicts.

Today, what remains of the complex has been restored and has Unesco World Heritage status. There’s a museum dedicated to Ledoux and his designs, exhibitions about salt production and the history of the saltworks, meeting centers, an annual garden festival, a hotel, a restaurant and a bar.

Free Town Christiania, Denmark

Christiania, the autonomous neighborhood in Copenhagen formed in 1971, was founded by a journalist deep into the free love movement. Jacob Ludvigsen envisioned a self-sustaining society built from scratch—though using preexisting buildings, since the site had abandoned army barracks already—with a goal of maintaining the psychological and physical health of a group over that of an individual. In practice, things quickly fell apart. Drugs took hold, and residents didn’t want to cooperate with the police. Christiania became a home for hard narcotics and a “green light district” for selling marijuana.

Drugs and crime are still a problem in Christiania, but the commune continues to thrive. The neighborhood today runs on tourism dollars from shops, restaurants and local events. Houses are beautifully painted and the entrance to the neighborhood takes visitors through a sculpture park made from reclaimed and recycled items.

Palmanova, Italy

This town may be a fortress, but Palmanova was also created to be a utopia by the superintendents of the Republin of Venice—a self-sustaining community where everyone was equal and had a purpose, in a city that also just happened to be a death machine. It was built in 1593 to protect the Venetian Empire from invasions by the Austrian and Turkish militaries. The fortress is a nine-pointed star with three rings expanding out from a hexagonal center. It was a geometrically perfect city, but alas, no one wanted to live there. The Venetian Empire couldn’t lure residents into a contained city that lacked freedom to move around and also had the very real risk of constant war and devastation. So instead, the military stayed and in 1622, a large number of pardoned prisoners moved in to government-deeded properties—though it's unsure if they lived by the utopian ideals the city was founded on.

Now, the soldiers and prisoners have moved out of Palmanova, and the residents Italy tried so desperately to attract have officially entered. About 5,400 people live inside the walls. There’s a campaign going to get Unesco status applied to the city, but as of now it's only received National Monument status from the Italian government.

Penedo, Brazil

In 1929, a group of Finnish settlers moved from Finland to Brazil, founding the colony of Penedo under the tutelage of pastor Toivo Uuskallio, who was convinced god wanted him to start a Finnish utopia in the tropics. According to the community rules, everyone was vegan, no one smoked or drank, and everyone worked together on a farm with no income. Penedo ran that way until 1942, when the residents finally realized it wasn’t sustainable to run a town with no money.

Tourism took over shortly after Penedo began to fall apart, and now the area is known as a Finnish enclave in Brazil. There’s a folk dance group that has regular performances, inns, shops, saunas (Penedo was home to Brazil's very first sauna), restaurants and a section called Little Finland that replicates the experience of the original settlers. Even Santa has a house in the town, where he will welcome guests all year.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)