The United States is teeming with wilderness waiting to be explored, whether it’s national park land, national forests, battlefields, lakeshores, parkways, preserves, trails, or more. This summer is the perfect opportunity to get out into those spaces, while still practicing social distancing and taking any necessary safety precautions to curb the spread of COVID-19, of course.

Some of these places were preserved by the government with little discussion, while others were subject to decades of fighting just to get the land recognized. You can visit these seven spots across the U.S. thanks to little-known heroes who made an effort to preserve them.

It’s important to call attention to the lack of diversity among these environmentalists, though—historically, saving the planet has been perceived as an overwhelmingly white endeavor due to the erasure of communities of color and their work to preserve the environment. For that reason, the first featured environmental hero on this list is MaVynee Betsch, a black woman who pushed to save her own community from destruction.

NaNa Sand Dune, Florida

Tucked between two luxury resorts, Florida’s tallest sand dune, NaNa, rises 60 feet to overlook the historic village it protects, American Beach. Founded in 1935, the town was built and owned by Florida’s first insurance company, the Afro-American Life Insurance Company. The president of the company, Abraham Lincoln Lewis, saw the need for blacks around the country to have a place to vacation. So at his insistence, the insurance company bought up 200 acres on Amelia Island, right off the coast below the Georgia state line and 45 minutes northeast of Jacksonville. American Beach gained instant popularity, becoming a thriving destination for black business and entertainment—attracting even the likes of Duke Ellington and Ray Charles, who performed at nightclubs in the town. By the late 1950s, though, the town was floundering. Desegregation—although great for the community at large—left black establishments languishing. Black people visited white establishments, but few white people supported black-owned businesses. By the mid-1960s, American Beach was in danger of being sold off to the highest bidder as resorts overtook Amelia Island.

It was at this point that MaVynee Betsch took action. Lewis’ great-granddaughter, Betsch grew up in American Beach. Lewis was the first black millionaire in Florida, and his profits left his family very well off. Betsch attended the best schools, graduated from prestigious Oberlin College, and moved to Europe where she began a ten-year opera career. When she returned full-time to American Beach in 1975, the town was falling apart. Betsch put her substantial inheritance and fortune to work, donating to about 60 different environmental causes—focused both nationally and on Amelia Island itself—throughout her life. She ended up living on the actual beach of her childhood, and would routinely climb the dunes behind the town—the dunes she named NaNa, as if they were a member of her family. So when the dune system and land was purchased by resort company Amelia Island Plantation in 1995, she again went to work. Betsch wrote nonstop letters pushing for preservation of the dune to Jack Healan, the resort’s president, and to state lawmakers. This continued until 2002, when Healan finally agreed to donate 8.5 acres of land, including the dune, to the nearby National Park Service's Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve. NaNa officially joined the preserve in 2003. Access to the dunes is currently permitted, and Timucuan has open trails and boat ramps. Two exhibit panels are up at the dune that explore the past and present of the site.

Fernbank Forest, Georgia

When Emily Harrison was growing up in the late 1800s, her favorite place was the woods on her family’s summer estate near Atlanta. Her father, Colonel Z. D. Harrison, bought 140 acres of woodland in 1881, building a home there as a gathering place for friends and family. Harrison described it—a place she called Fernbank Forest—in an unfinished letter to a friend, Miss Bowen, that she wrote in 1891 when she was 17 years old:

“The woods are all around, the great trees growing so tall and close together that in some places the sun can hardly find its way through to flicker on the carpet of brown leaves and pine needles that strew the ground. … The house is situated on top of a high hill, on two sides are brooks which flow together in front and form what the country people, unpoetically call Pea-vine creek. I can catch a glimpse from my window of this stream as it winds like a silver thread between its fern-fringed banks. … What rambles I took over the hills—exploring expeditions I called them—coming home laden down with woodland treasurers, ferns, mosses, lichens and wild flowers. … But the happiest hours of all were those spent reading in a hammock out under the trees. I must tell you about this reading room of ours, ‘The Rest,’ we called it. You smile, but if you could see the spot you would think it appropriately named. It is at the foot of the hill. On one side is a great boulder in coloring shading from dark olive green to rich browns and silvery grays with a delicate tracery of mosses and vines; on another is the hill upon which Maiden Hair ferns are growing, on the third side is the brook, while the forth [sic] is but a continuation of the beach and maple grove, this small part of which we have claimed from the woods as our own.”

Harrison’s father died in 1935. One of ten heirs, she was concerned that burgeoning development in the area would claim the woods she loved so much. So instead of selling off her and her siblings’ property, by that time only 65 acres, she worked with local residents to form Fernbank, Inc., a corporation that would protect the land. She bought out her siblings so the company would have control of the forest. In 1964, Fernbank, Inc., entered into a partnership with the DeKalb County School District, allowing the schools to use the forest as a living laboratory for 48 years. The lease expired in 2012, and ownership of Fernbank Forest transferred to the on-site Fernbank Museum, which opened in 1992. The forest reopened as part of the museum in 2016, after a four-year restoration. Fernbank is currently open daily with face coverings required, limited capacity and pre-purchased timed tickets. The forest has more than two miles of trails, and the museum is full of live animals, fossils and more.

Balboa Park, California

Kate Sessions is best remembered not just for her legacy as a botanist and nursery owner, but also as the “Mother of Balboa Park.” The park opened as City Park in 1868, when San Diego civic leaders preserved 1,400 acres of scrub just northeast of downtown. City Park would remain undeveloped for more than 20 years—when Sessions finally arrived.

In 1892, Sessions was already well known as a botanist. She was part-owner of the San Diego Nursery, owned a number of other nurseries throughout the area, and ran a flower shop. (Later, in 1906, Sessions helped found the San Diego Floral Association.) She wanted to open a commercial nursery in San Diego—on 32 acres already set aside for City Park. In exchange for the land, Sessions promised to plant 100 trees every year for 10 years, plus add 300 more trees and shrubs around San Diego. In doing so, she introduced many of the popular exotic plants in the park and throughout the city: Lily of the Valley, Hong Kong Orchid trees, birds of paradise, poinsettia, bougainvillea, among others.

For San Diego’s first world’s fair, the 1915-1916 Panama-California Exposition, park officials renamed City Park as Balboa Park—after Vasco Núñez de Balboa, the first European explorer to discover the Pacific Ocean. San Diego’s second world’s fair, the 1935 California Pacific International Exposition, was held partially in Balboa Park, and it was at this time that Sessions was christened with her nickname. She died in 1940, but many of her original plants and trees are still visible within the park, which now includes 17 museums, 10 dedicated performance spaces, the San Diego Zoo, the California Tower and nearly 20 gardens. Areas of the park are reopening in accordance with state and county regulations.

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska

Mardy and Olaus Murie were a power couple of the Alaskan wilderness. They met in Fairbanks in 1921, where Mardy had lived with her family and had just become the first woman to graduate from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, known then as the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines. The two married in 1924.

Olaus, who was a biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (then known as the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey), and Mardy instantly joined forces in a common goal to preserve wilderness. They spent their honeymoon boating and dogsledding across more than 500 miles of Alaska to conduct research on the migratory patterns of caribou. The two conducted similar research throughout North America, moving to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in 1927 to track the local elk herd. Even with Wyoming as home base, they made regular trips to the Arctic wilderness in Alaska.

In 1956, Mardy and Olaus (no longer employed by the Wildlife Service) gathered a group of field biologists and led a trip to Alaska’s upper Sheenjek River, located on the southern slope of the Brooks Range. The intent of the trip was clear: they wanted to conduct research that would convince the federal government to preserve the area—and the 8 million acres surrounding it—as the Arctic National Wildlife Range. Together, the couple managed to persuade former U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Douglas into convincing President Eisenhower to make their dream a reality in 1960. Olaus died four years later.

After Olaus’ death, Mardy continued with her environmental activism, winning another victory in 1980. President Carter doubled the size of the Range and renamed it the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Mardy died in 2003. The refuge is currently open for visitors to camp, hike, rock climb, forage for berries,and watch wildlife. Keep in mind there's no cell phone coverage in the refuge.

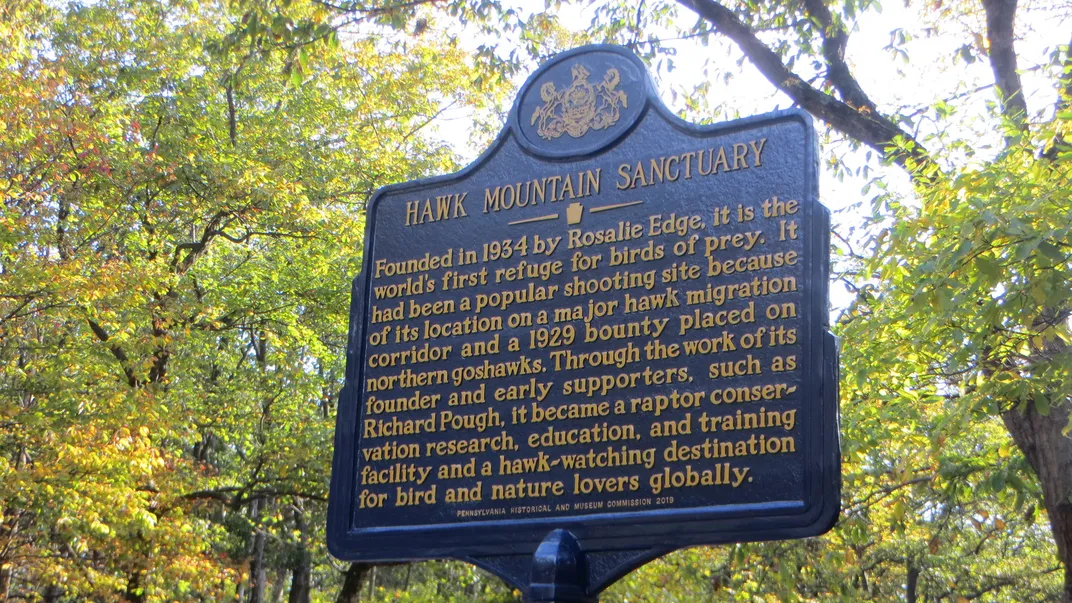

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Pennsylvania

In 1929, a 52-year-old suffragist named Rosalie Edge took the Audubon Society to task. She had come upon a pamphlet called “A Crisis in Conservation” while spending the summer in Paris. In it, the authors detailed how the Audubon Society, then called the National Association of Audubon Societies, teamed up with game hunters to make money. The society would rent its preserves and sanctuaries to the hunters, and in return for that cash flow, the hunters were able to kill as many creatures as they wanted.

Edge, an avid birder and wildlife supporter, was outraged. She went to the next society meeting, sat in the front row, and grilled the men in charge on the issue for so long that they decided to end the meeting early. After that meeting, she founded a group called the Emergency Conservation Committee (ECC) and sued the Audubon Society in order to get access to their mailing list—to which she mailed that incriminating pamphlet.

Three years later, she took that energy from New York City to Pennsylvania, where she confronted the Game Commission. She had learned through a photographer, Richard Pough, that Pennsylvania’s Game Commission was handing out $5 to anyone who killed a goshawk, which was considered a rodent bird at the time—and it was quickly becoming a slaughter. Pough showed Edge photos of piles of goshawk carcasses on the forest floor. Edge quickly took action, heading out to the location (known locally as Hawk Mountain) and leasing 1,400 acres, with a loan by conservationist Willard Van Name. On that land she installed a game warden, who refused to take a salary, to enforce a strict no-shooting rule. In 1935, she opened the land as a public preserve for people to come and see the birds. Three years later, she officially bought the land and founded the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary. All of Hawk Mountain's eight-plus miles of trail are currently open for hiking and birding. Watch for raptors like the Peregrine falcon, bald eagle, red-tailed hawk and those goshawks that Edge fought so hard to protect.

Smoky Mountains, Tennessee and North Carolina

In 1917, when Harvey Broome was 15 years old, he got a taste of the Smoky Mountains that never left him. His father took him camping at Silers Bald, where the current Appalachian Trail crosses the Tennessee and North Carolina border, and it launched a love for the mountains he spent 50 years exploring. He loved spending time in the mountains so much, in fact, that after he became a lawyer, he quit to take a lower ranking position as a law clerk—solely because it afforded him more time to spend outdoors. When he married, he and his wife, Anna, owned a cabin in the Smokies—their base for exploration—and a house up on a ridge in Tennessee with a mountain view. Today, Great Smoky Mountains National Park stretches 522,427 acres, split almost perfectly down the middle by the Tennessee-North Carolina border.

In 1935, Broome and seven others—Aldo Leopold, Robert Marshall, Robert Sterling Yard, Benton MacKaye, Ernest Oberholtzer, Bernard Frank and Harold C. Anderson—founded the Wilderness Society, an organization working to care for and protect wild places throughout the country. When, in 1966, his beloved Smokies were threatened by the development of a highway that would cut through the wilderness, Broome, then serving as president of the Wilderness Society, took action. He organized a Save Our Smokies hike, attended by more than 1,300 people, that was instrumental in stopping the road construction, keeping the Smokies street-free for generations to come.

Visitors to the park can enjoy hiking more than 850 miles, fishing in more than 2,000 miles of water, biking, horseback riding, watching wildlife and visiting waterfalls. Facilities throughout the park like visitors' centers, picnic areas and concessions are reopening in phases.

Boundary Waters, Minnesota

Sigurd Olson’s fight to preserve the Boundary Waters wilderness area, one million acres stretching along northern Minnesota's Canadian border, began in the 1920s. He started campaigning to restrict human activity in the Boundary Waters, and his efforts were not met with cooperation. With 1,175 lakes and more than a million acres of wilderness, the area was used for motorized boating, fishing and snowmobiling—and fans of those activities felt threatened by Olson's crusade. He pushed for a float plane ban in the 1940s, angering the local community of outdoorsmen. Olson fought against roads and dams, and did everything he could to keep the Boundary Waters pristine. But, at times, he incited outright hate in his critics. In 1977, for instance, motorboating and logging advocates who disagreed with his vision hung an effigy of him from a logging truck outside an Ely congressional hearing, advocating for more restrictions on motorboats, mining and logging in the Boundary Waters. When Olson was called to the stand, he was booed and shouted at, and even the judge couldn’t get the crowd back under control. But Olson had an articulate response about why the Boundary Waters needed protection: "Wilderness has no price. Tranquility, a sense of timelessness, a love of the land—how are you going to explain love of the land, how are you going to explain the value of a sunset or a lookout point?"

Ultimately, Olson won. A Boundary Waters bill passed in 1978, three years before Olson's death, officially naming the area the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Today, about 250,000 people visit the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness annually, to hike, canoe, fish, rock climb and camp. Boundary Waters is currently open for visitors.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/9c/fd9cf5d0-bc53-4893-905a-496ae940d5a4/great_smoky_mountain_national_park-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a7/cc/a7ccb917-fef3-4fa1-9bfa-99bf0785cd63/great_smoky_mountain_national_park-social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)