Shanghai Gets Supersized

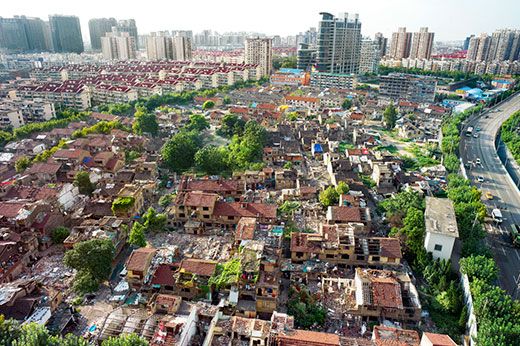

Boasting 200 skyscrapers, China’s financial capital has grown like no other city on earth – and shows few signs of stopping

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Shanghai-Oriental-Pearl-tower-631.jpg)

When building projects grew scarce in the United States a few years ago, the California architect Robert Steinberg opened an office in Shanghai. He says he didn’t understand the city until the night he dined with some prospective clients. “I was trying to make polite conversation and started discussing some political controversy that seemed important at the time,” he recalls. “One of the businessmen leaned over and said, ‘We’re from Shanghai. We care only about money. You want to talk politics, go to Beijing.’ ”

When I visited Steinberg’s Shanghai office, he led me past cubicles packed with employees working late into the evening. “We talk acres in America; developers here think kilometers,” he said. “It’s as if this city is making up for all the decades lost to wars and political ideology.”

Over the past decade or more, Shanghai has grown like no other city on the planet. Home to 13.3 million residents in 1990, the city now has some 23 million residents (to New York City’s 8.1 million), with half a million newcomers each year. To handle the influx, developers are planning to build, among other developments, seven satellite cities on the fringes of Shanghai’s 2,400 square miles. Shanghai opened its first subway line in 1995; today it has 11; by 2025, there will be 22. In 2004, the city also opened the world’s first commercial high-speed magnetic levitation train line.

With more than 200 skyscrapers, Shanghai is a metroplex of terraced apartments separated by wide, tree-lined boulevards on which traffic zooms past in a cinematic blur. At the 1,381-foot-tall Jin Mao Tower, whose tiered, tapering segments recall a giant pagoda, there’s a hotel swimming pool on the 57th floor, and a deck on the 88th floor offers a view of scores of spires poking through the clouds. I had to look up from there to see the top of the 101-story World Financial Center, which tapers like the blade of a putty knife. The Bank of China’s glass-curtained tower seems to twist out of a metal sheath like a tube of lipstick.

The last time I’d been to Shanghai, in 1994, China’s communist leaders were vowing to transform the city into “the head of the dragon” of new wealth by 2020. Now that projection seems a bit understated. Shanghai’s gross domestic product grew by at least 10 percent a year for more than a decade until 2008, the year economic crises broke out around the globe, and it has grown only slightly less robustly since. The city has become the engine driving China’s bursting-at-the-seams development, but it somehow seems even larger than that. As 19th-century London reflected the mercantile wealth of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, and 20th-century New York showcased the United States as commercial and cultural powerhouse, Shanghai seems poised to symbolize the 21st century.

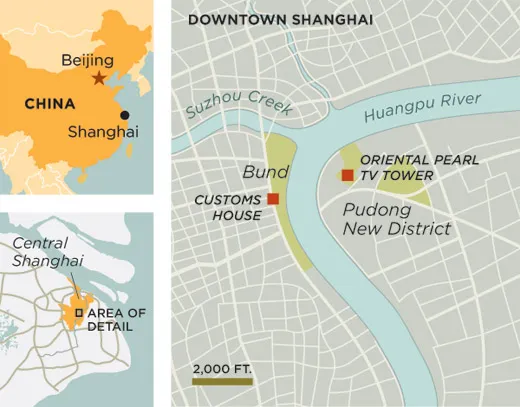

This is quite a transformation for a port whose name became synonymous with “abducted” after many a sailor awoke from the pleasures of shore leave to find himself pressed into duty aboard an unfamiliar ship. Shanghai lies on the Huangpu River, about 15 miles upstream from where the mighty Yangtze, the lifeblood of China’s economy for centuries, empties into the East China Sea. In the middle of the 19th century, the Yangtze carried trade in tea, silk and ceramics, but the hottest commodity was opium. After defeating the Qing dynasty in the first Opium War (1839-42), the British extracted the rights to administer Shanghai and to import opium into China. It was a lucrative franchise: about one in ten Chinese was addicted to the drug.

Opium attracted a multitude of adventurers. American merchants began arriving in 1844; French, German and Japanese traders soon followed. Chinese residents’ resentment of the Qing dynasty’s weakness, stoked partially by the foreigners’ privileged position, led to rebellions in 1853 and 1860. But the principal effect of the revolts was to drive half a million Chinese refugees into Shanghai; even the International Settlement, the zone where Westerners stayed, had a Chinese majority. By 1857 the opium business had grown fourfold.

The robust economy brought little cohesion to Shanghai’s ethnic mix. The original walled part of the city remained Chinese. French residents formed their own concession and filled it with bistros and boulangeries. And the International Settlement remained an English-speaking oligarchy centered on a municipal racecourse, emporiums along Nanjing Road and Tudor and Edwardian mansions on Bubbling Well Road.

The center of old Shanghai was known as the Bund, a mile-long stretch of banks, insurance companies and trading houses on the western bank of the Huangpu. For more than a century, the Bund boasted the most famous skyline east of Suez. Bookended by the British consulate and the Shanghai Club, where foreign entrepreneurs sat ranked by their wealth along a 110-foot-long bar, the Bund’s granite and marble buildings evoked Western power and permanence. A pair of bronze lions guarded the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank building. The bell tower atop the Customs House resembled Big Ben. Its clock, nicknamed “Big Ching,” struck the Westminster chime on the quarter-hour.

Beneath the opulent facade, however, Shanghai was known for vice: not only opium, but also gambling and prostitution. Little changed after Sun Yat-sen’s Republic of China supplanted the Qing dynasty in 1912. The Great World Amusement Center, a six-story complex packed with marriage brokers, magicians, earwax extractors, love-letter writers and casinos, was a favorite target of missionaries. “When I had entered the hot stream of humanity, there was no turning back had I wanted to,” the Austrian-American film director Josef von Sternberg wrote of his visit in 1931. “The fifth floor featured girls whose dresses were slit to the armpits, a stuffed whale, story tellers, balloons, peep shows, masks, a mirror maze...and a temple filled with ferocious gods and joss sticks.” Von Sternberg returned to Los Angeles and made Shanghai Express with Marlene Dietrich, whose character hisses: “It took more than one man to change my name to Shanghai Lily.”

While the rest of the world suffered through the Great Depression, Shanghai—then the world’s fifth-largest city—sailed blissfully along. “The decade from 1927 to 1937 was Shanghai’s first golden age,” says Xiong Yuezhi, a history professor at Fudan University in the city and editor of the 15-volume Comprehensive History of Shanghai. “You could do anything in Shanghai as long as you paid protection [money].” In 1935 Fortune magazine noted, “If, at any time during the Coolidge prosperity, you had taken your money out of American stocks and transferred it to Shanghai in the form of real estate investments, you would have trebled it in seven years.”

At the same time, Communists were sparring with the nationalist Kuomintang for control of the city, and the Kuomintang allied themselves with a criminal syndicate called the Green Gang. The enmity between the two sides was so bitter they did not unite even to fight the Japanese when long-running tensions led to open warfare in 1937.

Once Mao Zedong and his Communists came to power in 1949, he and the leadership allowed Shanghai capitalism to limp along for almost a decade, confident that socialism would displace it. When it didn’t, Mao appointed hard-line administrators who closed the city’s universities, excoriated intellectuals and sent thousands of students to work on communal farms. The bronze lions were removed from the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, and atop the Customs House, Big Ching rang in the day with the People’s Republic anthem “The East Is Red.”

The author Chen Danyan, 53, whose novel Nine Lives describes her childhood during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and ’70s, remembers the day new textbooks were distributed in her literature class. “We were given pots full of mucilage made from rice flour and told to glue all the pages together that contained poetry,” she says. “Poetry was not considered revolutionary.”

I first visited Shanghai in 1979, three years after the Cultural Revolution ended. China’s new leader, Deng Xiaoping, had opened the country to Western tourism. My tour group’s first destination was a locomotive factory. As our bus rolled along streets filled with people wearing Mao jackets and riding Flying Pigeon bicycles, we could see grime on the mansions and bamboo laundry poles festooning the balconies of apartments that had been divided and then subdivided. Our hotel had no city map or concierge, so I consulted a 1937 guidebook, which recommended the Grand Marnier soufflé at Chez Revere, a French restaurant nearby.

Chez Revere had changed its name to the Red House, but the elderly maitre d’ boasted that it still served the best Grand Marnier soufflé in Shanghai. When I ordered it, there was an awkward pause, followed by a look of Gallic chagrin. “We will prepare the soufflé,” he sighed, “but Monsieur must bring the Grand Marnier.”

Shanghai today offers few reminders of the ideology that inspired the Cultural Revolution. After the city’s Mao Museum closed in 2009, leftover statues of the Great Helmsman stood on a shuttered balcony like so many lawn jockeys. By contrast, many of Shanghai’s precommunist buildings look almost new. The former villa of the Green Gang leader lives on as the Mansion Hotel, whose Art Deco lobby doubles as a memorial to the 1930s, filled with period furnishings and sepia photographs of rickshaw pullers unloading cargo off sampans. The reopened Great World Amusement Center provides a venue for Chinese opera, acrobats and folk dancers, though a few bars are allowed.

As for the Bund, it has been restored to its original Beaux-Arts grandeur. The Astor House, where plaques commemorate Ulysses S. Grant’s post-presidential visit, and where Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard were summoned to dinner by liveried butlers bearing golden trumpets, is once again receiving guests. Across Suzhou Creek, the Peace Hotel (known as the Cathay when Noel Coward wrote Private Lives there during a four-day bout with the flu in 1930) recently underwent a $73 million restoration. The Shanghai Pudong Development Bank now occupies the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank building. Bronze lions have returned to guard duty at the entrance.

With the Chinese well into their transition to what they call a “socialist market economy,” it seems that they look upon the city not as an outlier, but as an example. “Every other city is copying Shanghai,” says Francis Wang, a 33-year-old business reporter who was born here.

Shanghai’s makeover began haphazardly—developers razed hundreds of tightly packed Chinese neighborhoods called lilongs that were accessed through distinctive stone portals called shikumen—but the municipal government eventually imposed limitations on what could be destroyed and built in its place. Formerly a two-block-long lilong, Xintiandi (New Heaven and Earth) was torn down only to be rebuilt in its 19th-century form. Now the strip’s chic restaurants such as TMSK serve Mongolian cheese with white truffle oil to well-heeled patrons amid the cyberpunk stylings of Chinese musicians.

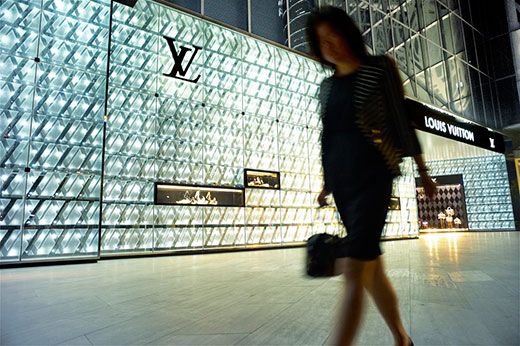

Nobody arrives at Xintiandi on a Flying Pigeon, and Mao jackets have about as much appeal as whalebone corsets. “Shanghai is a melting pot of different cultures, so what sells here is different from other Chinese cities,” says fashion designer Lu Kun, a Shanghai native who numbers Paris Hilton and Victoria Beckham among his clients. “No traditional cheongsams or mandarin collars here. Sexy, trendy clothes for confident, sophisticated women; that’s Shanghai chic.”

Xia Yuqian, a 33-year-old migrant from Tianjin, says she knows “lots of Shanghainese women who save all their money to buy a [hand] bag. I think it’s strange. They want to show off to other people.” But Xia, who moved to the city in 2006 to sell French wine, also relies on Shanghai’s reputation for sophistication in her work. “When you go to other cities, they automatically think it’s a top product,” she says. “If you said you were based in Tianjin, it wouldn’t have the same impact.”

In Tian Zi Fang, a maze of narrow lanes off Taikang Road, century-old houses are now occupied by art studios, cafés and boutiques. The Cercle Sportif Francais, a social club in the colonial era and a pied-á-terre for Mao during the communist regime, has been grafted onto the high-rise Okura Garden Hotel. “A decade ago this structure would have been destroyed, but now the municipal government realizes that old buildings are valuable,” says Okura general manager Hajime Harada.

The old buildings are filled with new people: Nine million of Shanghai’s 23 million residents migrated to the city. When I met with eight urban planners, sociologists and architects at the Municipal Planning, Land and Resources Administration, I asked how many of them had come from outside the city. They greeted the question with silence, sidelong glances and then laughter as seven of the eight raised their hands.

Pudong, the district Deng had in mind when he spoke of the enormous dragon of wealth, was 200 square miles of farmland 20 years ago; today, it is home to Shanghai’s skyscraper district and the Shanghai Stock Exchange, which has daily trading volumes of more than $18 billion, ranking seventh worldwide. The jade-colored stone used for curbing around the Jin Mao Tower may strike an outsider as a bit much, but for Kathy Kaiyuan Xu, Pudong’s excess is a source of pride. “You must remember that ours is the first generation in China never to know hunger,” says the 45-year-old sales manager for a securities company. Because of China’s policy of limiting urban married couples to one child, she said, “families have more disposable income than they ever thought possible.”

Materialism, of course, comes with a cost. A collision of two subway trains this past September injured more than 200 riders and raised concerns over transit safety. Increased industry and car ownership haven’t helped Shanghai’s air; this past May, the city started posting air-quality reports on video screens in public places. Slightly less tangible than the smog is the social atmosphere. Liu Jian, a 32-year-old folk singer and writer from Henan Province, recalls when he came to the city in 2001. “One of the first things I noticed was there was a man on a bicycle that came through my lane every night giving announcements: ‘Tonight the weather is cold! Please be careful,’” he says. “I had never seen anything like it! It made me feel that people were watching out for me.” That feeling is still there (as are the cycling announcers), but, he says, “young people don’t know how to have fun. They just know how to work and earn money.” Still, he adds, “there are so many people here that the city holds lots of opportunities. It’s hard to leave.”

Even today, Shanghai’s runaway development, and the dislocation of residents in neighborhoods up for renewal, seems counterbalanced by a lingering social conservatism and tight family relationships. Wang, the business reporter, who is unmarried, considers herself unusually independent for renting her own apartment. But she also returns to her parents’ house for dinner nightly. “I get my independence, but I also need my food!” she jokes. “But I pay a price for it. My parents scold me about marriage every night.”

In a society where people received their housing through their state-controlled employers not so long ago, real estate has become a pressing concern. “If you want to get married, you have to buy a house,” says Xia, the wine seller. “This adds a lot of pressure”—especially for men, she adds. “Women want to marry an apartment,” says Wang. Even with the government now reining in prices, many can’t afford to buy.

Zao Xuhua, a 49-year-old restaurant owner, moved to Pudong after his house in old Shanghai was slated for demolition in the 1990s. His commute increased from a few minutes to half an hour, he says, but then, his new house is modern and spacious. “Getting your house knocked down has a positive side,” he says.

When Zao starts talking about his daughter, he pulls an iPhone out of his pocket to show me a photograph of a young woman in a Disney-themed baseball hat. He tells me she’s 25 and living at home. “When she gets married, she’ll get her own apartment,” he says. “We’ll help her, of course.”

Shanghai’s development has created opportunities, Zao says, but he has kept his life simple. He rises early each day to buy supplies for the restaurant; after work he cooks dinner for his wife and daughter before trundling off to bed. “Every once in a while I’ll go around the corner to get a coffee at the Starbucks,” he says. “Or I’ll go out to karaoke with some of our employees.”

For others, the pace of change has been more unnerving. “I joke with my friends that if you really want to make money in China, you should open a psychiatric hospital,” says Liu, the singer. And yet, he adds, “I have many friends who are really thankful for this crazy era.”

Chen Danyan, the novelist, says, “People look for peace in the place where they grew up. But I come home after three months away and everything seems different.” She sighs. “Living in Shanghai is like being in a speeding car, unable to focus on all the images streaming past. All you can do is sit back and feel the wind in your face.”

David Devoss profiled Macau for Smithsonian in 2008. Lauren Hilgers is a freelance writer living in Shanghai. New Jersey native Justin Guariglia now works out of Taipei.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.