Sicily Resurgent

Across the island, activists, archaeologists and historians are joining forces to preserve a cultural legacy that has endured for 3,000 years

As it happened, I was with vulcanologist Giuseppe Patanè just three days after Sicily’s Mount Etna—at 10,902 feet, the tallest active volcano in Europe—erupted in October 2002. As Patanè, who teaches at the University of Catania and has spent nearly four decades clambering over Etna, stepped out of his green Renault to confer with civil defense officials, thunderous booms cracked from the erupting crater just half a mile away.

“Let’s track down the front of this lava stream,” he said, leaping back into the driver’s seat with boyish enthusiasm. On the way downhill, we spied carabinieri (police) jeeps hurtling out of the oak and chestnut forest. Patanè pulled over to chat briefly with one of the drivers. “We better hustle down the mountain fast,” he said to me when he had finished. “There’s a risk that a new crater could open.”

“Where?” I asked.

“Under our feet,” he replied with a fiendish grin.

As it turned out, the eruptions continued for weeks. Earthquake tremors nearly leveled the nearby town of Santa Venerina, leaving more than 1,000 people homeless. So much ash fell on Catania, 20 miles south, that the sky was black even at noon. Driving was dangerous in the slick, halfinch- deep volcanic dust. Even the streets of Syracuse, 50 miles south, were covered in ash.

Of course, eruptions of one sort or another have been rocking Sicily for millennia. In the fifth century B.C., the Greek poet Pindar alluded to Etna’s volcanic temper, marveling that its “inmost caves belch forth the purest streams of unapproachable fire.”

Poised about two miles off the toe of Italy, of which it is an autonomous region, Sicily is about the size of Vermont. It has seen waves of invaders, who left behind impressive monuments: Greek and Roman temples, Saracen citrus groves and gardens, Norman churches with glittering Byzantine mosaics, 17th- and 18th-century cathedrals erected by Spanish and Bourbon rulers. As a result, the island possesses one of the greatest concentrations of historical and archaeological landmarks in the Mediterranean.

Tourists flock to an island regarded as a sort of alternative Tuscany, a place that compensates for its dearth of Michelangelos and Botticellis with an exotic cultural identity that has one foot in Europe and the other in North Africa. Although films such as The Godfather convey the impression that the island is all blood, revenge and omertà (the code of silence), others such as 1989’s Cinema Paradiso, 1994’s Il Postino and 1950’s Stromboli, starring Ingrid Bergman, portray a gentler, more picturesque way of life closer to reality.

Compared with the rest of Europe, even mainland Italy, time here is divided less by minutes and hours than by mealtimes, when regional food, lovingly prepared, is served. Pasta with squid and mussels at the Santandrea restaurant in the capital city of Palermo; fish carpaccio at the Ostaria del Duomo restaurant in Cefalù; and roast pork glazed with the local Nero d’Avola wine at the Fattoria delle Torri in Modica are among the best meals I’ve ever eaten.

After Etna, the biggest eruptions in recent decades were the assassinations in Palermo of anti-Mafia judges Giovanni Falcone, in May 1992, and Paolo Borsellino two months later—brutal wake-up calls galvanizing the island to fight the Mafia and enact reforms. “When we heard the explosion from the enormous bomb that killed Borsellino, we stopped everything,” recalls Giovanni Sollima, 42, a composer. “After that point, it was like we all saw a new movie—Palermo rebuilding. We got drunk on Palermo, discovering the historic center for the first time—churches, paintings, buildings, new food, different cultures, dialects—as if we were tourists in our own city.” In 1996, Palermo’s airport was renamed Falcone- Borsellino in honor of the martyred judges.

After the murders of the two judges, Sicilians seemed to embrace their enormous cultural wealth as a way of overcoming the island’s darker reputation. Despite the assassinations, the trials of crime bosses went forward. Since 1992, more than 170 life sentences have been handed down by local prosecutors. As powerful, venal and pervasive as the Mafia continues to be—drug trafficking and corruption in the construction industries, for example, remain a problem—the majority of the island’s five million citizens reject it. Thanks to a vigorously enforced anti-street-crime campaign, Palermo, for the first time in decades, has now become a city where it is safe to walk, day and night.

And throughout the island, signs of this cultural revival are everywhere—in restorations of Noto Valley’s spectacular Baroque monuments in the southeast; in a privately sponsored project to conserve the rare flora and fauna of the Aeolian Islands, 25 miles to the north; in cooking schools, such as Anna Tasca Lanza’s classes at Regaleali, her country estate, near the central Sicilian town of Vallelunga; in a wide-scale effort to shore up the town of Agrigento’s mile-long stretch of Doric temples—one of the most extensive concentrations outside Greece itself—on the south coast, and, in 2002, in composer Sollima’s own sold-out performance of his opera at the restored 19th-century opera house opposite his studio.

Reopened in 1997 after 23 years of intermittent restoration, the Teatro Mássimo, a neo-Classical temple dominating an entire city block, symbolizes Palermo’s renaissance. Claudio Abbado conducted the Berlin Philharmonic at the gala opening; the opera house now showcases local and international talent. Film buffs might recognize the dark sandstone exterior from the opera scene in The Godfather: Part III, shot here in the late 1980s.

Seated in the Teatro’s royal box, its walls sheathed in velvet, former artistic director Roberto Pagano tells me that two churches and a convent were razed in the 19th century to make room for the original building, incurring the wrath of Catholic authorities and conservative politicians alike. Why erect this temple of luxury, critics asked, when the city lacks decent hospitals and streets? “They had a point,” Pagano acknowledges, surveying five horseshoe-shaped tiers of magnificently restored and gilded box seats.

An expert on Palermo-born composer Alessandro Scarlatti and his son, Domenico, Pagano has organized an annual Scarlatti festival. But he champions contemporary works as well. “Palermo was a center for experimental music in the 1960s and ’70s before the theater closed: we want to revive that reputation,” he says.

Few Sicilians approach the island’s cultural revival with more zest than Baroness Renata Pucci Zanca, the 70ish vice president of Salvare Palermo (To Save Palermo), a local preservation organization. She takes me to Lo Spasimo, a once-derelict 16th-century monastery recently transformed into a performance center. Entering the roofless nave of a former church now used for outdoor musical and theatrical productions, Zanca tells me that the interior, before it was given a new lease on life, had become a dumping ground, filled with “a mountain of trash 20 feet high.”

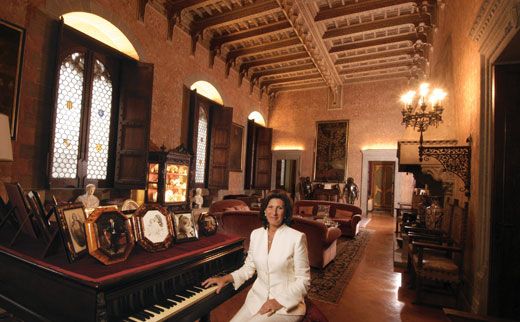

In the historic district surrounding Lo Spasimo, a squaremile area with a great profusion of medieval, Arab-Norman and Baroque buildings, Zanca next takes me on a tour of dilapidated palazzos. Some of these still bear damage from bombings in 1943, when the Allies captured Sicily. Others, such as Palazzo Alliata di Pietratagliata, only appear derelict; inside, tapestries, ancestral portraits and antique marquetry chests fill elegant drawing rooms. “Palermo is not like Rome, Venice or Florence, where everything is displayed like goods in a shop window,” says Princess Signoretta Licata di Baucina Alliata. “It’s a very secret city.”

To finance the palazzo’s upkeep, Alliata invites small groups of tourists to pay for the privilege of hobnobbing with Sicilian aristocrats in private palazzos. Dinner for 16, served in a sumptuous Baroque dining room with a soaring, trompe l’oeil ceiling and a gargantuan Murano chandelier, evokes a scene, and a recipe for “chicken livers, hard boiled eggs, sliced ham, chicken and truffles in masses of piping hot, glistening macaroni,” from The Leopard, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s 1958 novelistic portrayal of Sicily’s proud, crumbling 19th-century aristocracy.

Outside, Lo Spasimo’s streets teem with young people spilling from restaurants and bars. In the paved square in front of the Church of San Francesco d’Assisi, waiters at a sidewalk café bear late-night orders of pasta con le sarde—the signature Palermo dish of macaroni, fresh sardines, fennel, raisins and pine nuts. From a bar set back on a cobbled street, a jazz-rock trio belts out a tune by Catanian balladeer Franco Battiato.

One day I drive to Syracuse, once the center of Sicily’s ancient Greek culture and for 500 years Athens’ archrival. The route extends 130 miles southeast, through orange and lemon groves, wheat fields, vineyards and sheep pastures, past hill towns and a barren, semiarid region where the only signs of life are occasional hawks wheeling in the updrafts.

Arriving in late afternoon, I make my way to the amphitheater where, in the fifth century B.C., Aeschylus presided as playwright-in-residence. It was in Syracuse too, a century later, that Plato tutored the future king Dionysius II. In the fading light, the semicircular rows of white limestone glow a dusky pink, while in the distance, beyond blocks of modern apartment buildings, I can make out the ramparts where Archimedes mounted mirrors to set an invading Roman fleet on fire. Despite the great mathematician’s secret weapon, Syracuse ultimately fell to the Romans in 211 B.C.; thereafter, the city gradually slid into decline.

The following morning, Baron Pietro Beneventano, 62, a local preservationist and amateur historian, leads the way into Castello Maniace, a stone fortress built in the mid-13th century by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II.

Beneventano, whose ancestors settled in Syracuse in 1360, enters a vast reception hall. Aforest of massive, intricately carved columns punctuates the space. “No one had any idea this hall existed until the floor above it was removed during renovations,” the baron says. “Because of the incredible artistry and beauty of these columns, some are convinced Castello Maniace is the most important building Frederick II ever built.”

Back outside, Beneventano points out a construction crew digging at the castle’s seafront entrance, which was buried for centuries beneath mud and sand. The Italian Environment Foundation is restoring the fortress and more than a dozen city monuments threatened by modern development or neglect. “There are just too many monuments for the government alone to renovate,” Beneventano says. “Without private funding, some of Syracuse’s priceless legacy could vanish without a trace.”

A few hundred yards up a wind-swept promenade, past cafés and restaurants, lies the Fonte Aretusa, a sunken, springfed pool where Admiral Nelson replenished his water supplies in 1798 before setting off to defeat Napoleon at the Battle of the Nile, a victory that secured British control of the Mediterranean. While Nelson attended a ball held in his honor at the family palazzo, Beneventano tells me, the admiral learned that Napoleon’s fleet lay anchored near AboukirBay. “Just imagine,” Beneventano muses. “If Nelson had not stopped in Syracuse for water and news, it’s entirely likely he would never have known Napoleon was off the coast of Egypt. History might have turned out very differently.”

A half-hour drive southwest leads to Noto, a Baroque town (pop. 21,700) that exemplifies pioneering urban planner Giuseppe Lanza’s vision of harmonious equilibrium. After an earthquake destroyed Noto in 1693, it was rebuilt in a luminous honey-colored stone, tufa. In 1996, its cathedral’s dome collapsed, and local officials launched a campaign to restore the fragile tufa structures. There, in 2002, UNESCO listed the town and seven others nearby as World Heritage Sites, citing their unparalleled concentration of Baroque landmarks.

Noto’s triumphal stone arch, at one end of the piazza, opens onto ornate churches flanked by statues and bell towers and palazzos with wrought iron balconies supported by carved stone lions and centaurs and other strange beasts. At the town hall, students lounge on the broad steps, while nearby, cafés, ice-cream parlors, boutiques selling hand-painted ceramic plates, and vest-pocket parks planted with palm trees and bougainvillea anchor a lively street scene.

Inside the Church of Monte Vergine, atop steep stairs 100 feet above the piazza, a restorer painstakingly applies epoxy resin to a once-proud facade pockmarked by three centuries of exposure to the elements. “How is it going?” I ask.

“Nearly finished,” he replies. “But don’t worry, I’m not out of a job yet, there’s years more work ahead.” He nods toward the towering crane poised above the cathedral of San Nicolò; its dome is surrounded by scaffolding.

Fifty miles northwest of Noto, the world’s finest concentration of Roman mosaics are to be found near the town of Piazza Armerina. At the Villa Romana del Casale, there are 38,000-square-feet of vivid mosaics, many documenting the lives of fourth-century Roman aristocrats hunting, banqueting, celebrating religious festivals, chariot racing. The country house is so lavish that archaeologists speculate it may have been owned by Maximian, Diocletian’s co-emperor.

The mosaics’ remarkable state of preservation, architect Filippo Speranza tells me, is, ironically enough, the result of a cataclysmic landslide in 1611, which buried the villa until its excavation in 1955. “Now that the villa is exposed to the atmosphere, the packed earth [still] surrounding the walls allows moisture to seep into the mosaics and frescoes,” Speranza says. To eliminate this seepage, the site needs to be excavated to its original level, an enormous task that will require digging out another five feet around much of the villa.

Apart from a cavernous banquet hall adorned with images of the 12 labors of Hercules, the villa’s most impressive work illustrates an African and Indian safari. An elephant struggles in a net, a wounded lioness attacks a hunter, a panther sinks its teeth into an antelope. Although the mosaic undulates like a wave across a partially caved-in floor 200 feet long and 10 feet wide, it has remained miraculously intact.

Speranza believes that only a small fraction of the Roman settlement has been uncovered. “The villa was far more than the hunting lodge most people thought at first,” the archaeologist says. “In reality, it served as an important administrative center to represent Rome’s interests at the periphery of the empire.”

Leaving Villa Romana, I retrace my route northwest, bypassing Palermo to reach the coastal nature reserve of Zingaro, about an hour and a half drive west of the capital and the site of a showdown more than two decades ago that put the brakes on Sicily’s chaotic overdevelopment.

In May 1980, some 6,000 demonstrators, representing local, national and international environmental groups, blocked a proposed highway through forested headlands near the coves of the Castellammare del Golfo. As a result, the regional assembly set aside six square miles for the reserve. Since then, some 90 regional nature reserves, parks, wetlands and marine sanctuaries have been created around the island.

Along the road to Zingaro lies Scopello, for centuries a center of tuna fishing until overfishing did it in during the 1980s. Inside a two-room visitors’ center 200 yards from Zingaro’s entrance, a man in his late 60s perches on a stool, weaving a basket from palm fronds. When I ask how long it will take him to finish, he lays down the knife he is using to plait the fronds and rotates the zigzag-patterned basket admiringly in one hand. “A day,” he says at last. “But since there are no more tuna for me to fish, I’ve got plenty of time.”

Inside the car-free sanctuary, dwarf palms and purple cornflowers edge a rust-red dirt path snaking along a rocky bluff above the coast. Far ahead, slender eight-foot-tall stalks of wild fennel poke above the scrub brush on cliffs that plunge hundreds of feet to the sea.

I pick my way down to a pebbly cove. The crystalline waters are fringed with red and orange algae; in a darkened grotto, incandescent shrimp glimmer in tide pools. Beyond the promontory of 1,729-foot MountGallo, rising into gray clouds, lies Palermo, only 35 miles away, with its labyrinthine streets, markets and hushed churches alongside exuberant piazzas bristling with outdoor cafés and ice-cream stands.

It seems a near-miracle that this wilderness exists so near the city, and I silently thank the protesters who blocked the highway 25 years ago. Like the millions of Sicilians horrified by the murders of judges Falcone and Borsellino, the demonstrators proved that there is an alternative to cynical power politics and Mafia rule. Sicily’s preservationists are part of that movement, helping to sustain a Mediterranean culture reaching back nearly 3,000 years.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.