Five Colossal Stone Portraits Around the World

Carved out of rock, these massive monuments go beyond Mount Rushmore

:focal(538x304:539x305)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/20/542080ca-c492-4456-a67d-1606cf2c7b04/decebalus.jpg)

From Mount Rushmore in the United States to the Sphinx in Egypt to the giant Leshan Buddha in China to the maoi statues of Easter Island, there are numerous colossal, so-tall-you-have-to-crane-your-neck-to-see-them rock carvings around the world. But for every recognizable statue, there rests another carving elsewhere in the world that may be less familiar, but equally impressive. Here are five of them.

Nemrut Dağ, Turkey

During his reign from 70 B.C. to 38 B.C., Hellenistic King Antiochus I of Commagene commissioned a sculpture of his own likeness, flanked by several deities and animal guardians. Located in Nemrut Dağ (also known as Nemrut Dağı), a national park that spans one of the tallest peaks of the Taurus Mountains in southeastern Turkey, the notable carvings sit in front of a funerary mound that towers 164 feet above the craggy landscape. Workers sculpted the ambitious mortuary complex using fragments of local limestone, but despite its scale, many centuries passed before it was rediscovered in 1881 by German surveyor Charles Sester. During the excavation, archeologists also found sandstone stelae featuring relief carvings of Antiochos’ ancestors with inscriptions noting the genealogical links. The site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1987. Over time, the heads of many the sculptures have detached from their bodies, falling and resting on the ground below. This is possibly due to weathering and other natural causes, as the carvings are located in an earthquake zone.

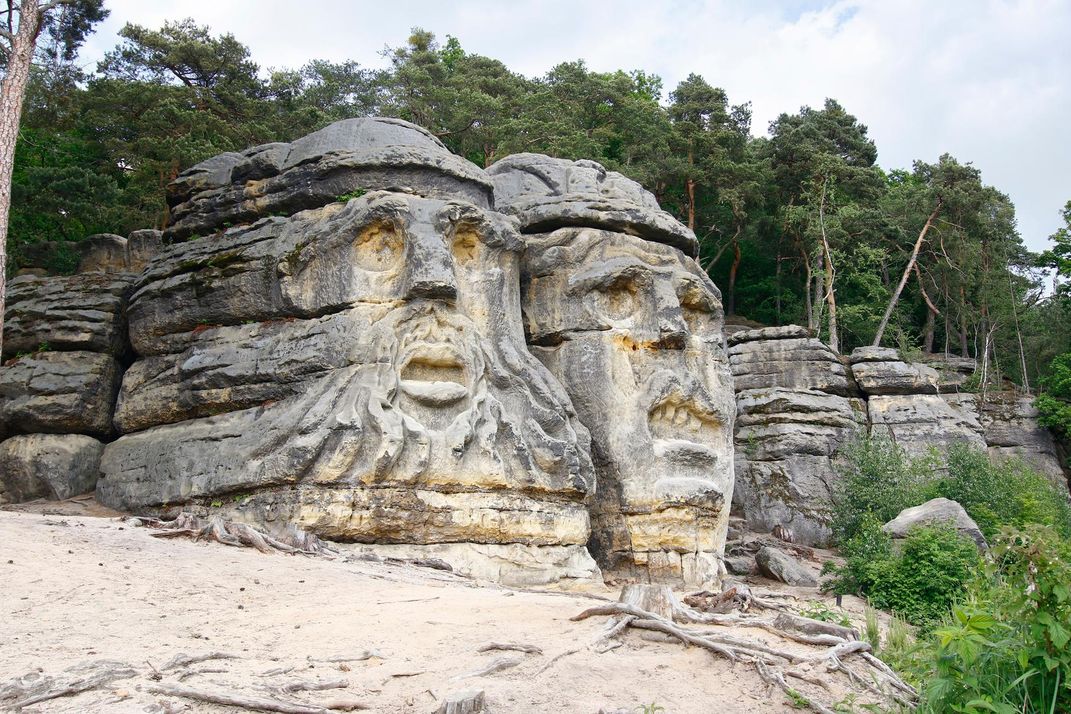

The Devil Heads, Czech Republic

Sometimes called the “Czech Mount Rushmore,” the Devil Heads (locally known as Certovy Hlavy) can be accessed in the northern part of the Czech Republic where an expanse of dense forestland gives way to the village of Želízy. With their hollowed-out eyes, the ghoulish-looking, twin-figured reliefs carved into the side of the cliff are the stuff of childhood nightmares. Reaching 30 feet in height, the two menacing faces are the creation of Czech sculptor Václav Levý, who carved them in situ from 1841 to 1846. Nearby, another of Levý's works called Klácelka features animal reliefs and scenes inspired by the fables of Czech poet and philosopher František Klácel. Both sculptures were carved early in Levý's career while he was working as a cook at the Liběchov castle.

Bayon Temple, Cambodia

Some 200 faces are carved into the exterior walls of Bayon Temple in Cambodia. But it's the four reliefs of what is believed to be the likeness of King Jayavarman VII, ruler of the Khmer Empire in present day Siem Reap, that are the most striking (pictured above). Some experts believe that the carvings show the king under the guise of Avalokiteś-vara, a famous bodhisattva who, according to Buddhist beliefs, had the capacity to reach nirvana. The Buddhist temple was built sometime during the king’s reign, which lasted from 1181 to 1218, and each of the four portrait carvings point toward one of the four cardinal directions. In addition to the faces, the temple's 54 towers contain bas-reliefs depicting historic events, such as battles and daily Cambodian life.

Decebalus Rex, Romania

Standing on the banks of the Danube River at an impressive 180 feet in height, with a 23-foot nose and 14-foot eyes to match, the monument to Decebalus, the king of the Dacians, is visible from a great distance. (By comparison, the presidential faces depicted on Mount Rushmore reach a mere 60 feet in height.) Dr. Giuseppe Costantino Dragan, the founder of the Dragan European Foundation, an organization that promotes European culture and education, put Italian sculptor Mario Galeotti to the task of creating a massive, modern-day carving in honor of the king, after selecting the location on the Romanian mountain in 1985. The site is significant since it's believed to be the same spot where Trajan's Bridge once stood, marking the site of Decebalus' defeat by former Roman emperor Trajan in 105 A. D. Following various delays, the project got underway in 1993, ultimately reaching completion more than a decade later.

Olmec Heads, Mexico

No one quite knows for sure what caused the Olmec people of Mesoamerica to vanish sometime around 300 B.C., but they did leave behind multiple reminders of their existence carved into stone—or, more specifically, volcanic basalt. Over the years, archeologists have discovered more than a dozen of these carved heads, which range in height from five to 11 feet and weigh approximately 20 tons each. Experts believe that they depict rulers of the Olmec civilization and were carved sometime between 1200 and 900 B.C. Today, many of the heads remain near their discovery sites in San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, Mexico. Three have been moved to and can be viewed at the Parque-Museo La Venta in Villahermosa, Mexico.

Correction: The article previously stated that Dr. Giuseppe Costantino Dragan purchased the location of Decebalus Rex in 1985. Although he identified the location in 1985, he did not purchase the land until 1993.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/9f/ce9f9921-98d6-4d22-a9ff-3b0785abf56b/bayon_temple.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/54/20/542080ca-c492-4456-a67d-1606cf2c7b04/decebalus.jpg)