Six Wonders Built by Pioneering Women Architects

Virtually explore these groundbreaking designs around the world, from an Italian villa to an American castle

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c9/08/c9085344-b3dd-415a-8d26-5c038f027bb8/hearst_castle_main.jpg)

In 2014, the BBC aired a three-part documentary called The Brits who Built the Modern World, featuring heavyweight architects Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, Nicholas Grimshaw, Terry Farrell and Michael Hopkins. There was a problem, though. Patty Hopkins, wife of Michael Hopkins and co-founder of Hopkins Architects, known for designs including the Glyndebourne Opera House in Sussex and the Frick Chemistry Lab at Princeton, was photoshopped out of promotional materials, leaving a group of just five men.

"I am shocked that women’s contribution to architecture has again been 'airbrushed' from this populist history programme," Lucy Mori from KL Mori Business Consulting for Architects told Architect's Journal at the time.

Yet, the incident builds on what we already know: historically, women have been erased from architecture.

Often, women have been second place to men in architecture firms, as evidenced by the BBC snafu. And, in other cases throughout history, working women architects, in an effort to survive in the business, disguised their efforts so well that no solid record links them to having designed anything at all. Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham’s supposed 1704 design of Wotton House in Surrey, England, is a great example of this. Wilbraham, an aristocratic Englishwoman who lived from 1632 to 1705 and studied architecture, is rumored to have designed 400 buildings. Wotton House, a 17th-century Baroque country estate commonly believed to be designed by William Winde, was attributed to Wilbraham by architectural historian John Millar based on designs she made for her family—though no drawings or invoices have her signature.

Not until 2004 did a woman, Zaha Hadid—the architect behind China's Guangzhou Opera House, Scotland's Riverside Museum and the London Aquatics Centre—win the Pritzker Prize, the most esteemed award in architecture.

“[Throughout history,] there was the exclusion of women in architecture education and in the profession,” says Ursula Schwitalla, editor of the upcoming book Women in Architecture from History to Future, which discusses great achievements of women architects both now and throughout history. “After centuries of exclusivity with only male architects, never women, the boom in the women’s movement at the end of the 19th century [allowed women] to gain admission to the profession. They had to fight for it, and they did.”

Like Hadid, women architects today are breaking boundaries and pushing architectural styles forward. Japanese architect Kazuyo Sejima, for example, won the Pritzker Prize with her partner in 2010; she designed the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art in Kanazawa, Japan, with a focus on expertly blending public and private spaces. German architect Anna Heringer, as well, is creating new styles, but focusing on sustainable materials and buildings. These women and others wouldn't be able to do the work they're doing today without the foundation built by women architects throughout history who broke down barriers and challenged the norm in order to create.

Honor pioneering women architects in history by virtually exploring these six architectural wonders around the world.

Château de Chenonceau, Chenonceaux, France

In France’s Loire Valley, Château de Chenonceau is an impressive sight—the estate actually stretches across the River Cher. When Katherine Briçonnet’s husband, Thomas Bohier, bought the property in 1513, it was just a run-down manor and mill. According to Women in Architecture from History to Future, Briçonnet supervised the renovation project and the addition of a pavilion while her husband was away—work that included leading the overall design. She’s most known for a staircase she designed inside the house, a straight one that led to the second story. It was the first straight staircase in French history; prior to that, only spiral staircases were used. Briçonnet was so proud of her work on the house and pavilion that she had an inscription carved above the door to the courtyard: “S’il vient à point, me souviendra,” or, “If it is built, I will be remembered.” The property is currently closed to visitors due to the pandemic; in normal operation, you can tour the castle and gardens. Virtual tours pop up regularly on the castle's Facebook page.

Villa Benedetti, Rome, Italy

When Plautilla Bricci was commissioned to build the Villa Benedetti (also known as Villa Vascello) in Rome in 1663, she became not only the first woman architect in Italy, but also the first known professional woman architect in world history. The building’s owner, Elpidio Benedetti, was the brother of Bricci’s art teacher, Eufrasia Benedetti della Croce. Bricci had started her career as a painter before she had a change of heart.

“She learned painting in the studio with her father,” Schwitalla says. “[But then] she said, no, I don’t want to paint, I want to build [the buildings] my paintings are in. And so she got the commission to build the Villa Benedetti.”

Bricci designed the villa to look like a Baroque ship, with curved walls, loggias and elaborate stucco work. The interior was covered in frescoes, some painted by Bricci herself. Though she was well-known as the architect for the building, when Benedetti published a description of the building in 1677, he credited Bricci’s brother with the design. Even though she was officially the architect, it was still outside social norms to acknowledge a woman architect. Unfortunately, most of the building was destroyed in the 1849 French siege of Rome. The remainder of the building, a three-story yellow and white mansion, is currently owned by Grande Oriente d’Italia, the national headquarters for freemasons in Italy. The public is free to attend Masonic meetings, or take a slideshow tour on Grand Oriente d'Italia's website.

Hotel Lafayette, Buffalo, New York

Louise Blanchard Bethune, the United States’ first woman architect, was a force to be reckoned with. When the construction department of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago announced in 1891 that they were looking for a woman architect to design one of the buildings, she loudly and notably objected. She was adamant that women should be paid as much as men, and as such, refused to compete for the $1,000 prize, which was pittance compared to the $10,000 paid to men who designed for the exposition.

More than a decade later, in 1904, the construction of Buffalo, New York’s Hotel Lafayette was completed. Blanchard Bethune was the chief architect on the project, a 225-room red brick and white terra-cotta French Renaissance style hotel. Each guest room in the hotel had a working telephone and both hot and cold running water, which was considered groundbreaking and a novelty at the time. The hotel is still in operation and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010. While no virtual tours are available, it's possible to visit the hotel and have a look around. You can also register for an overnight ghost tour.

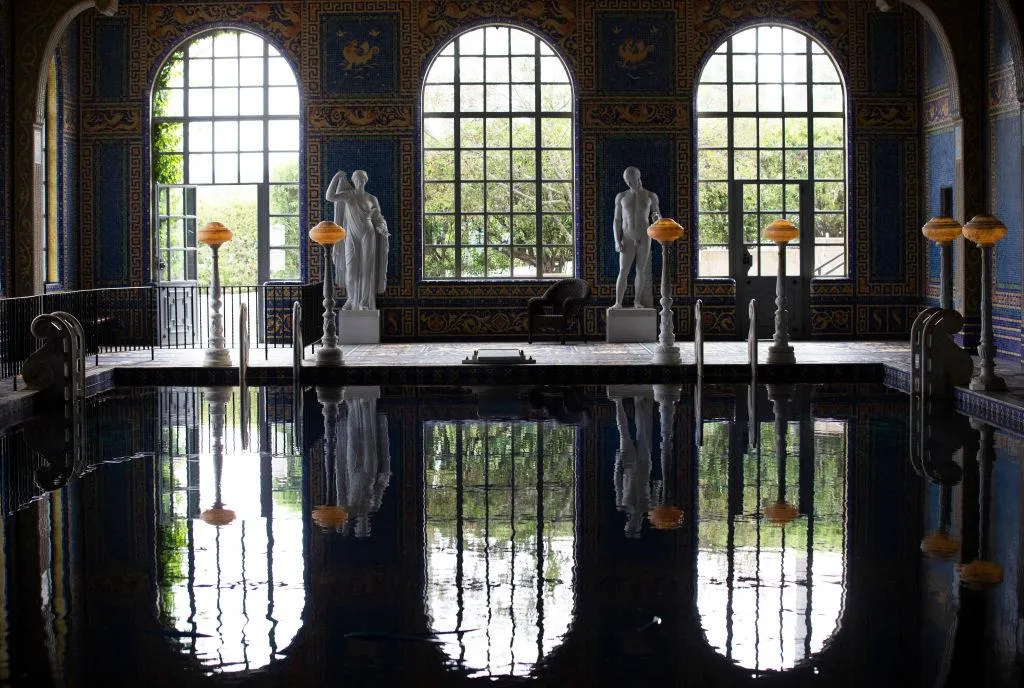

Hearst Castle, San Simeon, California

Architect Julia Morgan may have designed hundreds of buildings, but she’s best known for California’s Hearst Castle, which mixes Spanish Colonial, Gothic, Neo-Classical and Mediterranean Revival style all in one property. Morgan began her education studying engineering in California, but moved to Paris afterwards to become the first woman ever admitted to the architecture program at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1898.

“She [finished the program] in three years,” Schwitalla says. “Her colleagues, male architects, needed four or five years. But she did it in three.”

Morgan returned to the U.S. in 1902 and became the first licensed woman architect in California, starting her own firm in 1904. Newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst hired her in 1919 to build Hearst Castle and the surrounding guesthouses. Morgan worked on the project for the next 28 years, personally designing nearly every aspect of the project. She brought in Icelandic moss, reindeer and Spanish antiques. She helped Hearst seamlessly integrate his art collection into the buildings. She even designed the castle's private zoo, which consisted of both native and exotic animals, like bears, zebras, leopards and camels. Hearst initially started selling the zoo animals in 1937 when he hit financial trouble, but like the castle, that endeavor was never completely finished. Today, visitors can still see zebras grazing in warm weather. When Hearst could no longer afford it, construction stopped in 1947. The castle, now a museum, is currently closed due to pandemic restrictions, but you can take virtual tours on the Hearst Castle official app.

Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, England

In 1926, the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon burned down. Shortly after, an international architecture competition took place to find a replacement. More than 70 people submitted designs—including just one woman, Elisabeth Scott. At the time, the UK had only been training women in architecture for nine years. When the judges picked her design as the winner in 1928, the media was shocked, publishing stories with headlines like “Girl Architect Beats Men” and “Unknown Girl's Leap to Fame.” She was the first woman in the UK to win an international architecture competition.

The simple modernist design with Art Deco embellishments and Nordic influence was meant to both serve its purpose as a theatre and flow with the River Avon it sat along. It wasn’t received well by everyone—mostly, older men had problems with the design. But Scott was clear through the entire process what purpose her design served, noting in her acceptance of the win that, “I belong to the modernist school of architects. By that I mean I believe the function of the building to be the most important thing to be considered.”

When the theater officially opened in 1932, a crowd of more than 100,000 gathered and the entire spectacle was broadcast live to the United States. A number of renovations have been made on the building, and the theater is still in operation today, now known as the Royal Shakespeare Theatre. The theater is currently closed for full productions, but it is hosting online performances. It's expected to partially reopen on May 17 and fully reopen on June 21. In the meantime, take a virtual tour on the Royal Shakespeare Theatre's website.

UNESCO Headquarters, Paris, France

Architect Beverly Loraine Greene, born in Chicago in 1915, paved the way for black women architects. She was the first licensed black woman architect in the United States, earning that distinction in 1942. After a stint working with the Chicago Housing Authority, during which she faced pervasive racism and an inability to get jobs, she moved to New York City, where architecture work was easier to come by. Early on, she worked on the Stuyvesant Town project, a segregated housing community that didn't allow black residents in 1945. But from there she moved up the ranks, collaborating with modernist icons like Marcel Breuer. The two worked with two other architecture firms to design the Y-shaped UNESCO Headquarters in Paris. The building, which opened in 1958, is also called the "three-pointed star" and is famous for its groundbreaking construction method: the entire thing is held up by 72 concrete piling columns. Tours of the UNESCO Headquarters are available by appointment, but are currently on pause during the pandemic.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)