Emily Ginsberg, 84, stood with her arms clasped behind her back at the New-York Historical Society on a sunny Friday morning. She looked silently at a photo of a masked man staring at the camera, his left arm resting on the front driver’s side door of his SUV.

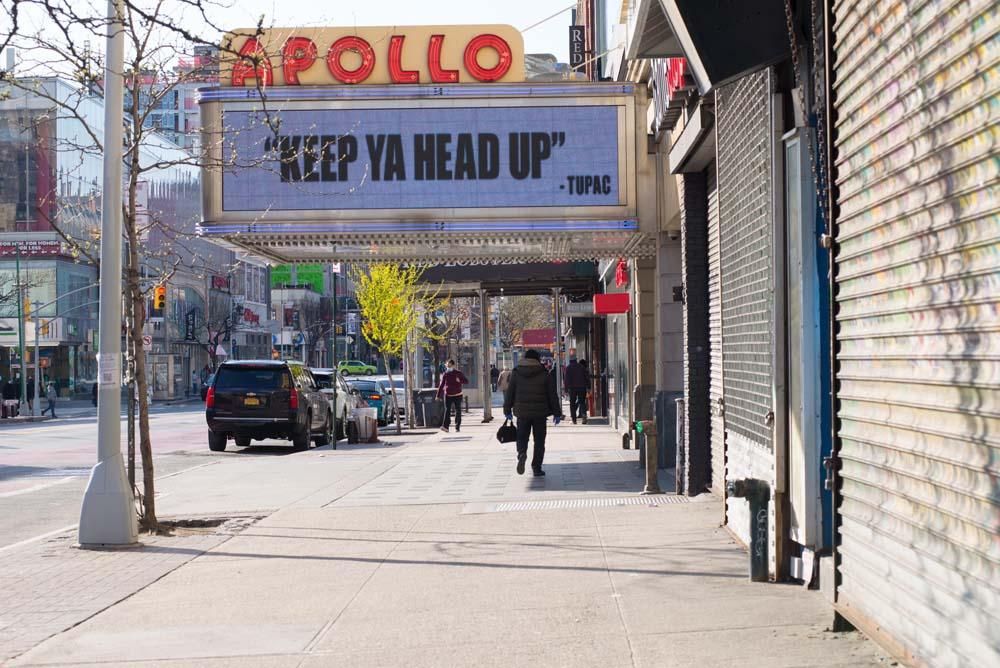

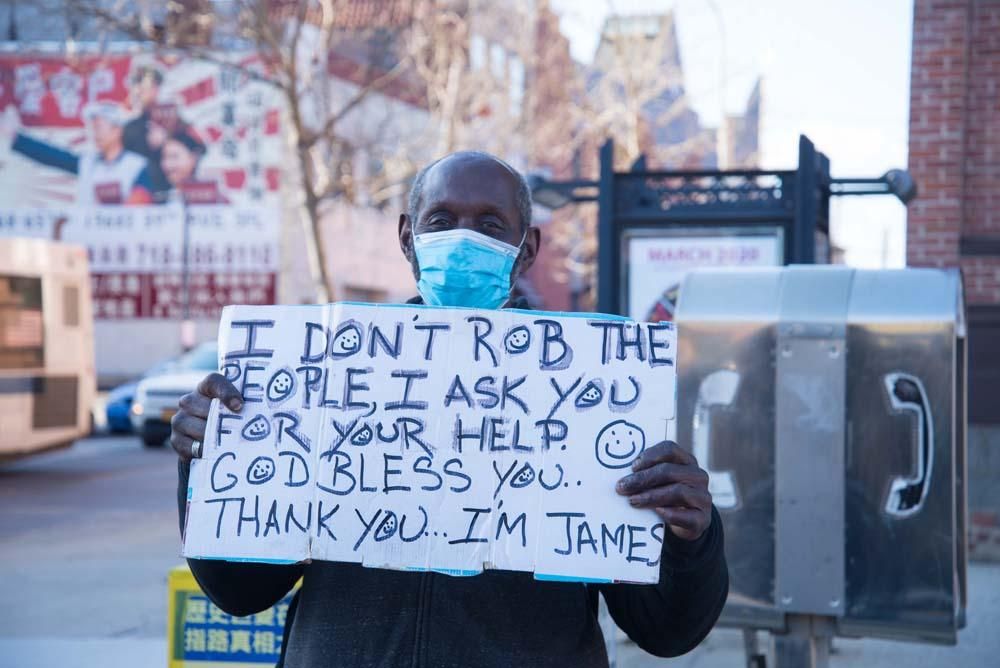

The photo is a part of “Hope Wanted: New York City Under Quarantine,” an exhibit of 50 photographs and 14 audio interviews with people who lived during the height of the Covid-19 epidemic in New York. The city has confirmed 18,998 deaths from the virus, but that number is expected to rise as more fatalities are counted. “Hope Wanted,” open through November 29, is one of the first new exhibits to open in the city after fears of contagion forced museums to shut down in March. An outdoor installation partly by design, and partly due to the state ordering museums to keep their indoor spaces closed until August 24, it’s divided in five sections, one for each borough. The result is an exhibit by, of, for and hosted by New Yorkers all struggling to feel their way through as of yet, an unsettled world.

Ginsberg spent the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic a block away from the museum, alone at her Upper West Side apartment, trying to keep herself busy. She expected to see a world unfamiliar to her own in the photographs. She did not know of anyone in her life who died of the virus. “Just humanity, just seeing people, everybody making do,” said Ginsberg, as she marveled at the photos and made her way to the Staten Island section. “I mean that’s the feeling that I have.”

Making do was all photojournalist Kay Hickman could do when her friend, Kevin Powell, called out of the blue in early April. Powell is a journalist and poet who has written for Vibe magazine, The Washington Post and Rolling Stone among others. Did she want to collaborate on an oral history project of New Yorkers during Covid-19? Hickman, who has relatives who were infected but recovered, jumped at the chance to get out of her Brooklyn home. “It was therapeutic for me; in a way it gave me a sense of hope,” she said. Hickman is also the first black woman photographer to have her work featured as the focus of an exhibition at the museum. Her portraits and street photography focus on the African diaspora and have been featured in The New York Times and Time magazine.

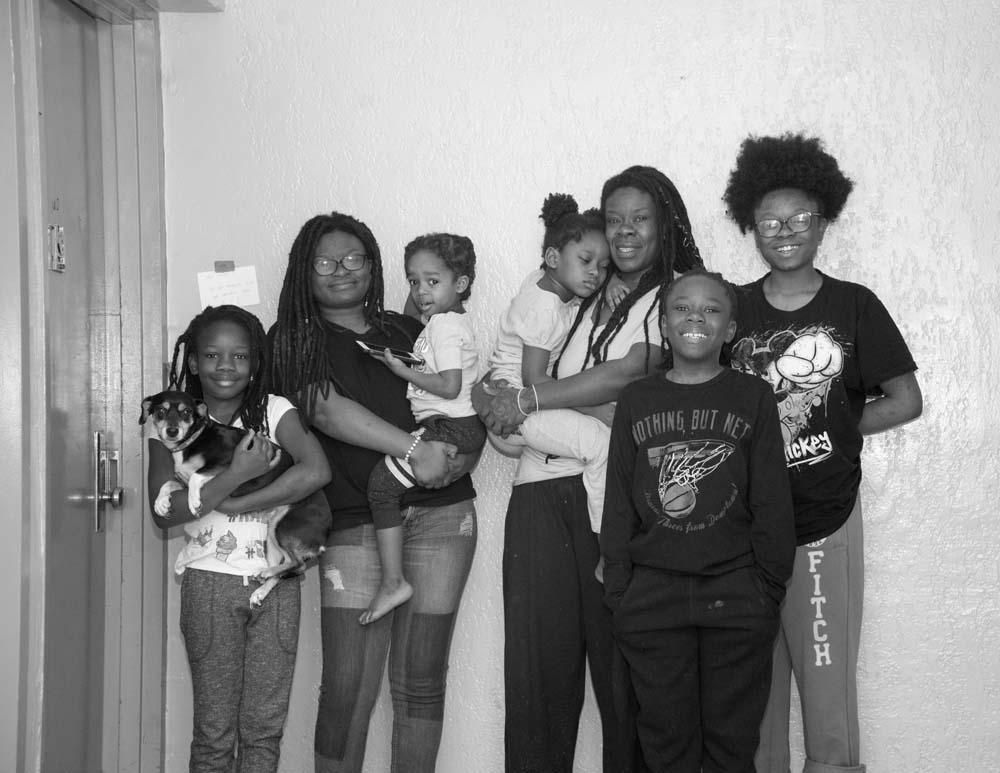

Hickman and Powell spent two days in early April interviewing and photographing people either previously known by Powell or referred to him by contacts all over New York City’s five boroughs. They interviewed a grave digger on Hart Island near the Bronx, where unclaimed bodies were buried. They photographed a mother who contracted the virus and her children in front of their Bronx apartment. They spent 12-hour days from the Bronx to Staten Island. Powell reached out to the Historical Society in mid-April, proposing a “healing space” with trees and greenery to encourage people to reflect.

“I first saw the photographs and listened to the stories when the coronavirus pandemic had just peaked in New York City,” said Margi Hofer, the vice president and museum director at the New-York Historical Society. “What struck me was that the ‘Hope Wanted’ project put a face to the crisis, revealing the personal experiences of a diverse group of people across five boroughs. My understanding of the pandemic was largely based on statistics and news footage, so I found it moving to listen to the intimate stories shared by these individual New Yorkers.”

Powell compares the human toll of Covid-19 in New York City to 9/11. “It was the same thing,” he said. “We were literally in the midst of everything that happened around that tragedy.” He wanted the space to act as an oasis from a city that is yet to roar back to life. The exhibit’s benches and trees give it the feel of a small enclosed park.

The comparison to 9/11 is apt, as it’s a shared tragedy, and provided Hofer with a blueprint for how to go forward. She is the only member of her team that was at the museum when it immediately mobilized and hosted a photography show of the attacks, by members of the photography cooperative Magnum, in November 2001. “It was a very healing exhibition,” she said. “We definitely had the sense that New Yorkers had a need for space to reflect and to try and understand the events. People were still feeling raw and confused and distraught. And so we see exhibitions like these as playing a really important role in helping people process tragedy and move on from it.”

The “Hope Wanted” exhibit had to be constructed first. Hofer originally thought it would be an indoor exhibit, but that idea simply wasn’t feasible due to the pandemic. “We started talking about the possibility of producing an exhibition in our back lot, because we started to realize it would be a long time before we could reopen,” she said. An outdoor exhibit would be safer for staff and visitors, but that also brought its own challenges. “We were required to get a permit from the Department of Buildings,” Hofer explained. “And a lot of our work hinged on getting that permit in place before we could start building the plywood walls around the perimeter.”

With the museum closed, Hofer’s team, accustomed to having at least a year’s lead time to prepare an exhibit like “Hope Wanted,” was dispersed, making it difficult to get team members on the ground to look at what was being constructed. So they took a shot in the dark.

“There were some decisions that we just had to make based on our best guesses. We were able to get proofs and check the printing quality, but in terms of mocking up text on site, there were some steps that we had to bypass,” Hofer said. Powell originally wanted music to accompany the exhibit, but Hofer quickly realized it wouldn’t work. “There's a co-op building that's just adjacent to the lot,” she said. “We had to move away from that idea pretty quickly.” Despite these challenges, the team worked quickly. “We put it together in three months,” she said.

A line of mostly elderly masked patrons stood, spaced six feet apart, right outside the exhibit on the morning of August 14, when it opened. They first had to face a body temperature scanner, and security guards ensured that people were properly spaced apart. The exhibit is designed to encourage visitors to walk in a linear path, with sections divided by borough. Markers are placed on the ground with directional arrows, both to guide visitors to other sections and to discourage people from congregating. People can start their way over again, and they do. The photos are of and directed towards people in their surroundings where the very act of going about their day could endanger their health. Visitors are greeted by a black and white photo of a mother who contracted Covid-19, her right hand wiping away tears while talking outside her Bronx apartment. They walk past pictures of empty airports and a nurse who traveled all the way from Oklahoma, clad in blue scrubs smoking a cigarette.

Many of the people profiled are people of color, which did not go unnoticed by Tamara Weintraub, 82, who ambled towards the Staten Island exhibit. “It's the truth that poorer people suffered much more, as they always do—people of color in that category—and it's one of the deficits in our society,” she said. Weintraub spent the worst of it alone as well, inside her apartment on the Upper East Side. Half of the tenants in her building left, to where, she does not know. When asked if she knew anyone who died from Covid-19, Weintraub said, “No, amazingly.”

The emphasis on working class New Yorkers is on purpose, according to Kevin Powell, who personally knew people who died of Covid-19. “I thought about all different races, cultures, identities. I thought about immigrants. I thought about the homeless community. I thought about poor people, because I come from a poor background,” he said.

Short audio interviews of some of the subjects can be listened to via QR code. The fact that this is still ongoing in this city gives a new twist on the concept of living history. Museumgoers aren’t seeing pioneers reenact how butter is made. Mask-wearing visitors are part of the attraction. The exhibit encourages them to record their Covid-19 experiences for possible future use. A visitor might record an experience of waiting in line for food at their Trader Joes, then leave for a nearby supermarket where they pace around in vain for Clorox wipes.

Joaquin Ramsey, 40, from Washington Heights peered at the Brooklyn section. He lives right by New York Presbyterian Hospital, where he heard the constant din of ambulance sirens. He and his family walked past the white tents the hospital erected to screen patients for the virus. The photos acted as a mirror.

“I saw a lot of our family in those pictures,” he said. “We were all at home, dealing with the kids trying to go to school, we were worried about our jobs. It's stressful and tiring. The thing that struck me the most was the fatigue and stress in people's eyes.”

Maria Alas, 24, also walked past the Brooklyn section. She lives across the Hudson River in New Jersey. She lost an uncle, who lived in Queens, to the pandemic in April. The lack of music worked for her. “This is more of a reflective silence, and you’re choosing to be silent rather than being subjugated to it,” she said. The first day of the exhibit pleased Hofer, and she sees the installation as a dry run for when the museum will finally reopen its doors on September 11. “I think [with] a lot of the safety protocols that we instituted for ‘Hope Wanted’ we are, in a sense, working out the bugs.”

This is the first event that Emily Ginsberg has bought a ticket for since March when museums closed. She found hope in Governor Andrew Cuomo’s daily briefings while stuck at home. She waited for the day when she could step outside on a sunny morning for fun. “It was just so nice to have something to come to,” she said.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/70/9f/709f3122-d88c-499a-b8bb-55b1fdb17bee/hope_wanted-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/35/1235d672-c77e-4284-9aa0-2f888d1ba668/hope_wanted-header.jpg)