This Breathtaking Greek Island Is Home to More Than 700 Churches

A major pilgrimage site for Orthodox Christians, Tínos has long been overlooked by other travelers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/d4/1fd4bf34-9f51-441b-96a4-d116893b973a/tl-greek-churches-1.jpg)

t was our second morning in Tínos, Greece, when we saw our first pilgrim. The woman, who appeared to be in her 60s, was crawling on her hands and knees along the street that leads from the port up a hill to the majestic Our Lady of Tínos church. Though it felt disrespectful to watch her intimate struggle, it was impossible not to keep turning back to follow her excruciatingly slow but deliberate progress.

Ever since an icon of the Virgin Mary credited with miraculous healing powers was found at the site of the church in 1823, thousands upon thousands of Christian pilgrims have made their way to this raw and beautifully pristine island, often to present the icon with silver and gold votive plaques and pray for a blessing. The greatest number of believers arrive in March, for the Feast of the Annunciation, and in August, for the Feast of the Dormition of the Virgin. Many of them crawl almost half a mile up to the Renaissance-style church, the most important Eastern Orthodox pilgrimage site in Greece.

"The Virgin Mary has saved Tínos," I was told by Maya Tsoclis, a Greek television personality who is based in Athens but spends more than half of the year on the island. And though she laughed, she wasn't really joking. Almost everyone I spoke to credited the Virgin with protecting Tínos from the fate that befell tourist-packed Mykonos, only a 30-minute ferry ride away but a world apart. "The pilgrims have scared both foreigners and Greeks away from here," Tsoclis said. "When I was growing up, everyone associated Tínos with being dragged by their grandparents to the Virgin Mary on smelly boats with food packed in Tupperware. The people on the ferry going to Mykonos, which is the next stop, were happy to pass Tínos by."

Tsoclis's TV show, Traveling with Maya Tsoclis, ran from 2007 to 2013, and during three of those years she also served in the Greek parliament. Now she and her husband, Alex Kouris, own the successful Cyclades Microbrewery on Tínos, and she puts out an ambitious annual magazine about the island, Tama, which means "votive" in Greek. "I have been to so many beautiful places, but sometimes there is a voice that whispers to you that you belong to a place," she said, describing the hold Tínos has on her. "Other Greek islands are only about the beach, but here it's also about the incredible villages you find inland."

One morning I followed Tsoclis in my car out of the main port — also called Tínos — away from the streets lined with tourist shops selling religious paraphernalia. Taking a narrow, winding road, we headed up into the hills, toward the village of Kampos, where her father, the renowned artist Costas Tsoclis, and her mother, Eleni, spend every summer. It was early April, and the rocky fields we drove by were covered in a haze of green grass and dotted with wild flowers — in contrast to the summer, when the land is dry and barren. We kept climbing upward, and occasionally I would spot a dovecote built into a slope or ravine. The island is home to hundreds of these stone towers, with fanciful geometric patterns cut into their façades, some meticulously maintained and painted bright white, others crumbling. They were built by the Venetians — who ruled Tínos for more than 500 years, ending in 1715 — and were used to raise pigeons for meat and fertilizer made from the birds' droppings.

When we arrived at Kampos, we parked at the edge of the village and entered on foot (almost all the villages on Tínos are car-free, because the ancient streets are too narrow). In the distance we could see craggy Mount Exomvourgo, the island's highest peak. Next to the Tsoclis family's old stone house is the Costas Tsoclis Museum, a whitewashed former school with an extension made of local stone, which displays dozens of the artist's works. Visitors to the museum (open June through September) are greeted in the front courtyard by Tsoclis's St. George and the Dragon, a multipart sculpture in which the saint is represented in a life-size wall relief and the beast by a 20-foot-long snaking metal tail. Despite being an atheist, Tsoclis — who is in his late 80s and continues to make new work — says he uses Christian symbols because "they carry the hopes of millions and millions of souls."

Tínos has attracted artists since antiquity, thanks in part to its famous marble quarries. On the outskirts of the lovely village of Pyrgos, the sleek stone-and-glass Museum of Marble Crafts leads visitors through exhibits ranging from how the stone is quarried to how it's carved. More interesting still is to stroll through Pyrgos and take in all the marble sculpture dotting the streets, from busts to bell towers, and the elaborately carved Christian symbols on the arched lintels embellishing almost every façade. The main square, surrounded by whitewashed buildings with cornflower-blue windows and anchored by an ancient plane tree, is stunningly beautiful, yet on the day I visited, there were no tourists in sight. I spent a lovely hour sitting at a café enjoying a slice of galaktoboureko, a semolina-custard pie, and exchanging glances with the only other person sitting in the square, a bearded Orthodox priest.

That kind of quietude is what makes Tínos such a prized sanctuary for people like Mareva Grabowski, cofounder of the Greek fashion label Zeus & Dione. Her family's house here, a cubic structure that seems to grow out of a rocky hill, looks out over the sea toward the island of Syros. Grabowski discovered Tínos almost 20 years ago, when she made a pilgrimage to the church to give thanks for her son's recovery from complications following a premature birth. "I promised I would pay tribute to the icon every year if my prayers were answered," she said. On her second visit, she missed the ferry back to Athens and found herself with a 10-hour wait until the next one. She hired a taxi to drive her around the island and was "mesmerized," she recalled, "by the views, the villages, the hidden beaches. It's been ten years since I built our house, and I am still discovering beaches."

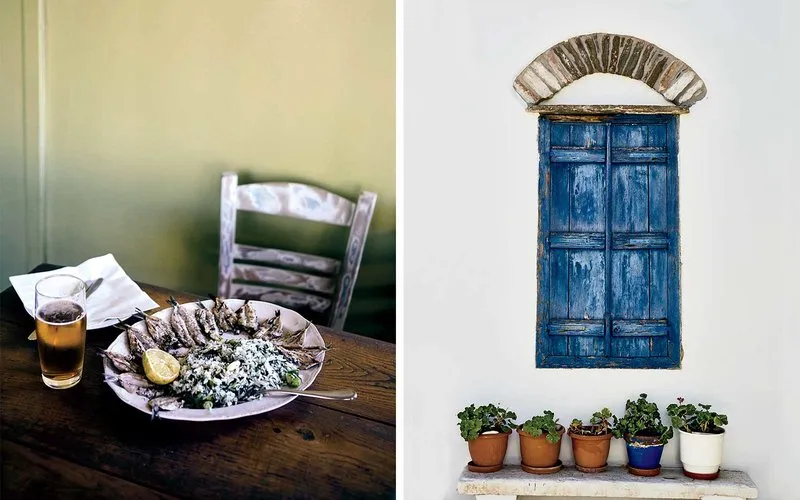

Grabowski's favorite culinary find on the island is a modest taverna called To Thalassaki, which sits appealingly right on the small Bay of Ysternia. In two weeks I made the trip three times, and I would have happily eaten there every day. On my first visit, I was joined by Maria Nikolakaki, founder of the vacation-home rental company Beyond Spaces Villas. When we entered the small room, all eight casually arranged tables were taken. The crowd was clearly sophisticated, and the effortlessly stylish scene seemed to reflect what Nikolakaki meant when she told me, "There is nothing pretentious on Tínos. This is an island for the person who is looking for the luxury of simplicity."

To Thalassaki's menu listed about 20 dishes, and I wanted all of them. The cuttlefish risotto, singing with lemon zest, was the best I'd ever had. Mussels with capers and anise were served with a garnish of wild fennel. A salad of fresh cucumbers and melon was sprinkled with feta and bee pollen. "We add four or five new dishes each year," said chef Antonia Zarpa, who has run To Thalassaki with her husband, Aris Tatsis, since 2000. "When I create recipes, I am drawing on culinary recollections of Tínos. I cook dishes that are inspired by memories of my grandparents."

To truly get to know this island, it's essential to get out and walk. It's the only way to access some of the most spectacular beaches and to explore the villages where people live almost as if the Industrial Revolution never happened. One morning Dimitris Papageorgiou, a hiking guide, led me, my husband, and our two girls on a four-hour excursion over ancient trails between picturesque towns.

"There are more than seven hundred churches on Tínos," Papageorgiou explained as we passed a hillside chapel barely big enough for one person. "Most of them are maintained by local families." In the little village of Volax, we came upon a shop selling artisanal baskets made from twigs. The old woman inside told us that the secret to harvesting the twigs was to "collect them during the full moon, because then they are without bugs." I couldn't help appreciating how, on this irresistibly peculiar island, lunar cycles and miracles are still central to everyday life.

One afternoon near the end of my stay, I visited the convent on Mount Kechrovouni named Sister Pelagia in her dreams, telling her where the island's famous icon was buried. Inside the fortified medieval complex, I came upon dozens of ancient houses and several churches — all of which appeared to be empty. Some 15 minutes went by before I ran in to anyone. A nun escorted me to the convent office. Sister Iouliano, the mother superior, an older, genial woman who spoke little English, showed me the library, which contained magnificent illuminated texts, as well as other spaces where precious treasures donated to the sisters are displayed. She brought me to the tiny room where the Virgin Mary is said to have appeared to Sister Pelagia. Sister Iouliano invited me to touch the pillow. As I tried to imagine holy visitations, the sister blessed me.

Walking to my car, the ever-present breezes (as more than one person told me, to love Tínos, you have to love the wind) suddenly kicked up and gave me a shiver. Despite having been raised a nonpracticing Christian, my visit to the nunnery, which had felt like a journey to a lost world, had moved me deeply. And as I drove through the rugged landscape, past centuries-old villages, I was sure I heard that whisper Tsoclis had spoken of — the island gently casting its spell and urging me to return.

Other articles from Travel + Leisure:

- The Best Places to See Fall Foliage in the United States

- Historic Chalet Burned Down in Montana Wildfires

- Australia Will Start Flying Shark-spotting Drones Over Beaches

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.