Learn the Secrets of the World’s Best Snow Sculptors

On the shores of Wisconsin’s Lake Geneva, teams of snow carvers turn chilly columns into masterpieces

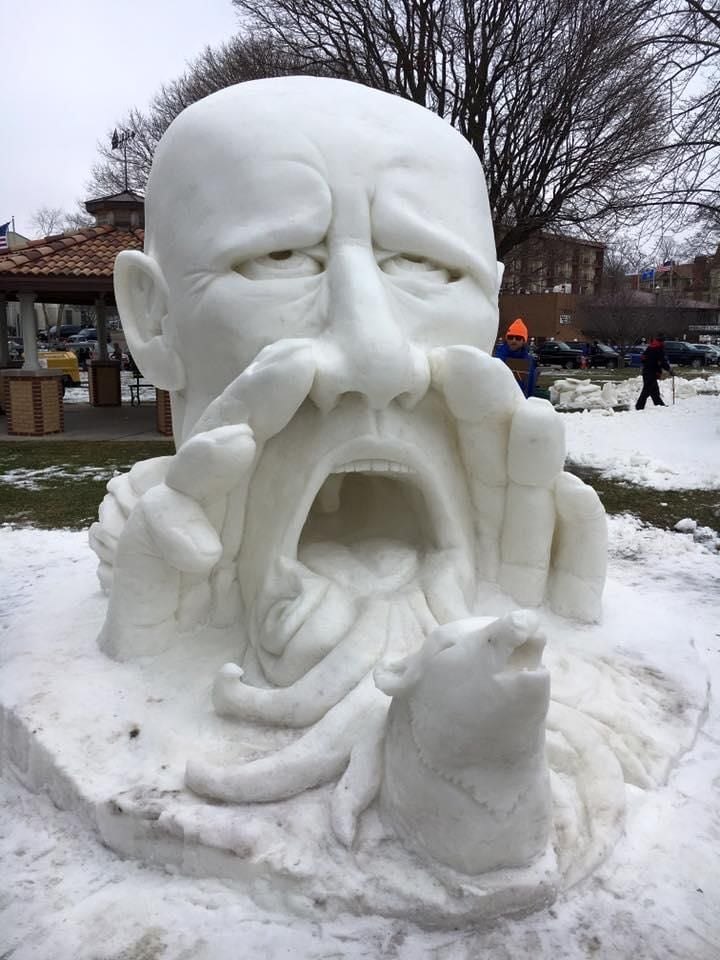

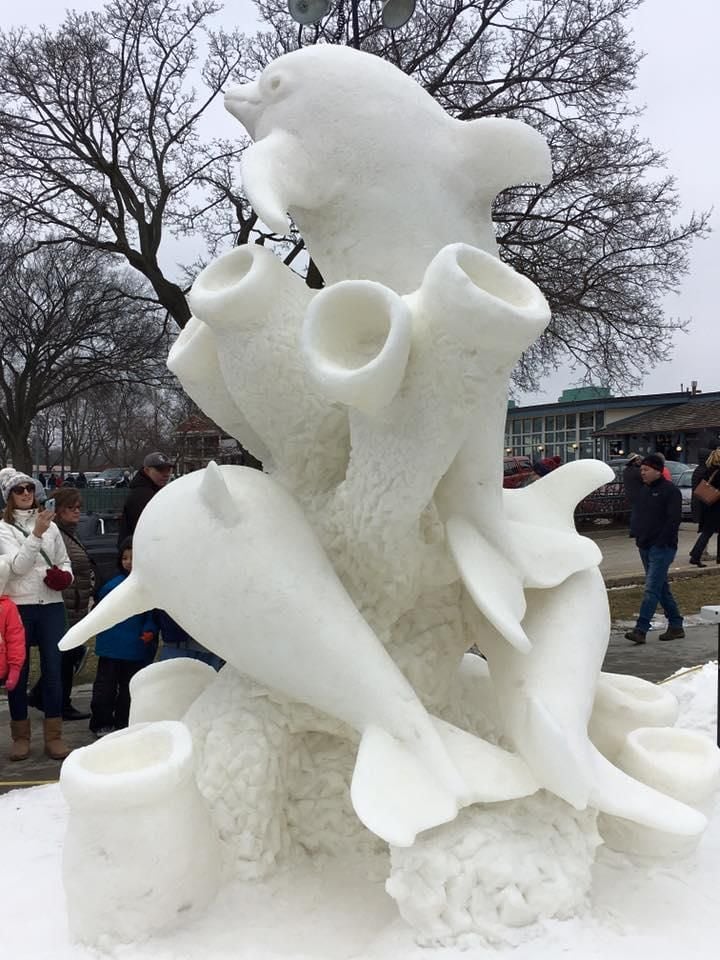

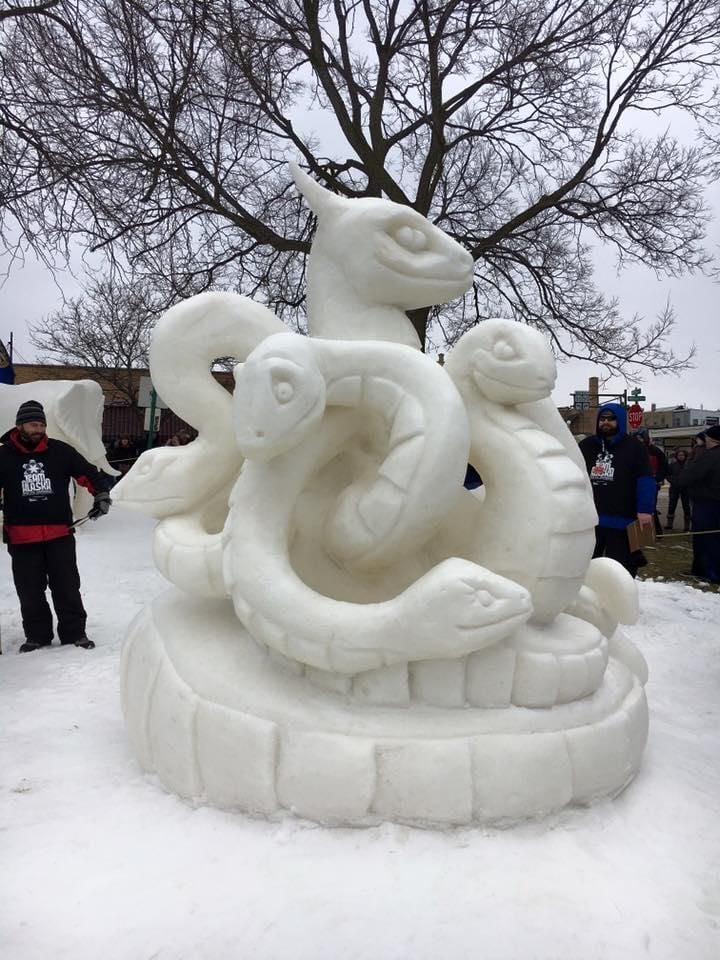

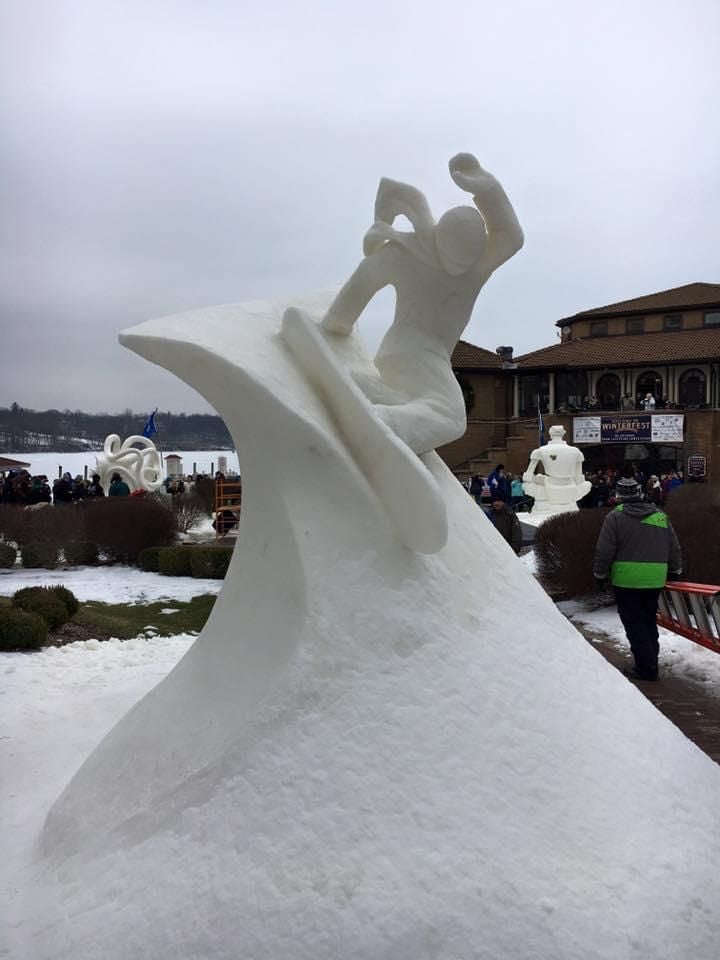

On the shore of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin during Winterfest, a fine spray of snow pelts visitors from every direction. It’s not because of flurries blowing off the water or a particularly bad winter storm. Rather, all that chilly commotion is generated by a small army of men and women tearing into huge snow blocks with saws, chisels and machetes for the U.S. National Snow Sculpting Competition.

The contest, held the first full week of February every year, brings the best snow sculptors from across the States to carve eight-by-nine-feet blocks of compressed snow into stunning pieces of art. More than 20,000 onlookers watch sculptors along the lakefront and in a plaza next to the pier as they work.

The snow, by the way, isn’t compressed mechanically—it’s loaded into a cylindrical mold, then teams of workers climb in and stomp the snow down so it’s packed firm. And it’s not produced by winter storms, either. All of the powder in the competition comes from snow guns at a nearby resort. This way, variations in the texture and purity of the snow won’t put some teams at a disadvantage. Snow gun snow also has a different crystal structure that makes it more packable and resilient to the elements.

A sculpture takes about 100 hours from conception to completion, with work split between up to three team members. Scaffolding surrounds the snow blocks throughout the week so sculptors can reach every inch of their piece, sometimes even straddling the top of the block to work up high. Sculptors use ice chippers to chop large amounts of snow off the block, chisels to create detail and remove small amounts of snow, sheetrock saws to cut through thick parts of the snow, and machetes to create curves and cut through small parts. But in truth, no standard set of snow sculpting tools exists—teams bring everything from sandpaper and truss plates to ice fishing augers and hatchets to the snow fight.

At the end of the week, six titles are bestowed upon the winning teams. The Champions Award, State of Wisconsin Award and City of Lake Geneva Award (gold, silver and bronze, respectively) are the overall winners and are voted on by the competitors themselves—and no, they aren’t allowed to vote for their own sculpture. The Spirit Award goes to a team that past winners think best represents the ideals of the competition, and the People’s Choice Award winner is picked by the crowd.

This year’s winning team, from Wisconsin, created an intricate piece showing an old man juggling different dimensions of space in various spheres. David Andrews, Gina Dilbirti and Zach Ruetzer didn’t just win the championship—they also clinched people’s choice. And they didn’t do it for the prize money: No cash prizes are given to the winners. Rather, snow sculptors compete for the love of the art and a chance at the title.

Want to level up your own snowman game? Take a page out of a snow sculptor’s handbook. Competitors Steve Bateman, Wade Pier and Andrews share some of their best tips for creating snow art:

Defy expectations: The initial idea needs to be creative enough to grab someone’s attention. Bateman likes to create sculptures that challenge standard concepts of size and perception, because then people stop and look. From there, come up with either a detailed sketch or a to-scale model to reference during sculpting.

Get rid of the extras: Start by removing the big chunks of snow you know you won’t need. Or, as Pier (whose Alaska-based team sculpted an owl) puts it, “take out all the snow that doesn’t look like an owl.” Then move in to get the smaller surfaces and detail.

Use the right tools: Make sure your tools are sharp and go over every inch of snow—don’t leave any surface unfinished. You’ll know when you’re completely done because the snow will start to look like “marble or Styrofoam,” Bateman says.

Let go: Whether you’re in a competition or your front yard, snow sculptors all warn not to get too attached. After all, says Bateman, it’s just going to disappear. “It’s ephemeral art,” he concludes. “I don’t mind that it’s going to melt and go away. Nothing lasts anyway.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)