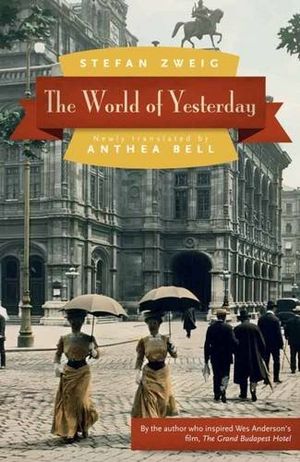

The Unhurried World of Pre-War Vienna

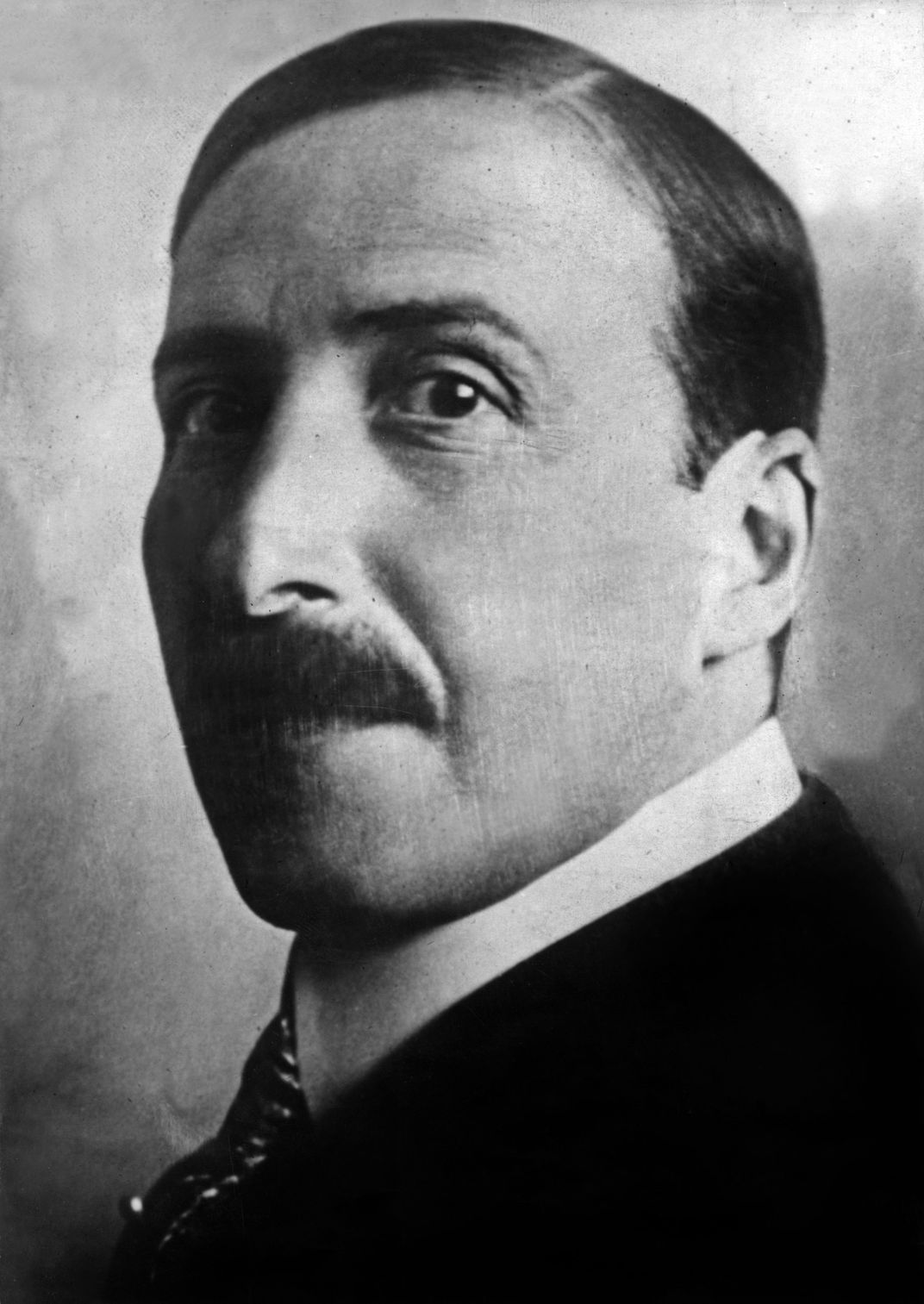

Author Stefan Zweig, who inspired Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, recalls Austria at the dawn of the 20th century

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e3/1e/e31e78d7-f196-4475-a9e8-79c9f622b802/sqj_1604_danube_timetravel_03.jpg)

One lived well and easily and without cares in that old Vienna, and the Germans in the North looked with some annoyance and scorn upon their neighbors on the Danube who, instead of being “proficient” and maintaining rigid order, permitted themselves to enjoy life, ate well, took pleasure in feasts and theaters and, besides, made excellent music. Instead of German “proficiency,” which after all has embittered and disturbed the existence of all other peoples, and the forward chase and the greedy desire to get ahead of all others, in Vienna one loved to chat, cultivated a harmonious association, and lightheartedly and perhaps with lax conciliation permitted each one his share without envy. “Live and let live” was the famous Viennese motto, which today still seems to me to be more humane than all the categorical imperatives, and it maintained itself throughout all classes. Rich and poor, Czechs and Germans, Jews and Christians, lived peaceably together in spite of occasional chafing, and even the political and social movements were free of the terrible hatred which has penetrated the arteries of our time as a poisonous residue of the First World War. In the old Austria they still strove chivalrously, they abused each other in the news and in the parliament, but at the conclusion of their Ciceronian tirades, the selfsame representatives sat down together in friendship with a glass of beer or a cup of coffee and called each other [the familar] Du. Even when [Karl] Lueger, the leader of the anti-Semitic party, became mayor of the city, no change occurred in private affairs, and I personally must confess that neither in school nor at the university, nor in the world of literature, have I ever experienced the slightest suppression or indignity as a Jew. The hatred of country for country, of nation for nation, of one table for another, did not yet jump at one daily from the newspaper, it did not divide people from people and nations from nations; not yet had every herd and mass feeling become so disgustingly powerful in public life as today. Freedom in one’s private affairs, which is no longer considered comprehensible, was taken for granted. One did not look down upon tolerance as one does today as weakness and softness, but rather praised it as an ethical force.

For it was not a century of suffering in which I was born and educated. It was an ordered world with definite classes and calm transitions, a world without haste. The rhythm of the new speed had not yet carried over from the machines, the automobile, the telephone, the radio, and the airplane, to mankind; time and age had another measure. One lived more comfortably, and when I try to recall to mind the figures of the grown-ups who stood about my childhood, I am struck with the fact that many of them were corpulent at an early age. My father, my uncle, my teacher, the salesmen in the shops, the members of the Philharmonic at their music stands were already, at forty, portly and “worthy” men. They walked slowly, they spoke with measured accent, and, in their conversation, stroked their well-kept beards, which often had already turned gray. But gray hair was merely a new sign of dignity, and a “sedate” man consciously avoided the gestures and high spirits of youth as being unseemly. Even in my earliest childhood, when my father was not yet 40, I cannot recall ever having seen him run up or down stairs, or even doing anything in a visibly hasty fashion. Speed was not only thought to be unrefined, but indeed was considered unnecessary, for in that stabilized bourgeois world with its countless little securities, well palisaded on all sides, nothing unexpected ever occurred. Such catastrophes as took place outside on the world’s periphery never made their way through the well-padded walls of “secure” living. The Boer War, the Russo-Japanese War, the Balkan War itself did not penetrate the existence of my parents. They passed over all reports of war in the newspapers just as they did the sporting page. And truly, what did it matter to them what took place outside of Austria...? In their Austria in that tranquil epoch, there were no state revolutions, no crass destruction of values; if stocks sank four or five points on the exchange, it was called a “crash” and they talked earnestly, with furrowed brows, about the “catastrophe.” One complained more as a habit than because of actual conviction about the “high” taxes, which de facto, in comparison with those of the postwar period, were nothing other than small tips to the state. Exact stipulations were set down in testaments, to guard grandchildren and great-grandchildren against the loss of their fortunes, as if security were guaranteed by some invisible promissory note by the eternal powers. Meanwhile one lived comfortably and stroked one’s petty cares as if they were faithful, obedient pets of whom one was not in the least afraid. That is why, when chance places an old newspaper of those days in my hands and I read the excited articles about some little community election, when I try to recall the plays in the Burgtheater with their tiny problems, or the disproportionate excitement of our youthful discussions about things that were so terribly unimportant, I am forced to smile. How Lilliputian were all these cares, how wind-still the time! It had better luck, the generation of my parents and my grandparents, it lived quietly, straight and clearly from one end of its life to the other. But even so, I do not know if I envy them. How they remained blissfully unaware of all the bitter realities, of the tricks and forces of fate, how they lived apart from all those crises and problems that crush the heart but at the same time marvelously uplift it! How little they knew, as they muddled through in security and comfort and possessions, that life can also be tension and profusion, a continuous state of being surprised, and being lifted up from all sides; little did they think in their touching liberalism and optimism that each succeeding day that dawns outside our window can smash our life. Not even in their darkest nights was it possible for them to dream how dangerous man can be, or how much power he has to withstand dangers and overcome trials. We, who have been hounded through all the rapids of life, we who have been torn loose from all roots that held us, we, always beginning anew when we have been driven to the end, we, victims and yet willing servants of unknown, mystic forces, we, for whom comfort has become a saga and security a childhood dream, we have felt the tension from pole to pole and the eternal dread of the eternal new in every fiber of our being. Every hour of our years was bound up with “the world’s destiny.” Suffering and joyful, we have lived time and history far beyond our own little existence, while they, the older generation, were confined within themselves. Therefore each one of us, even the smallest of our generation, today knows a thousand times more about reality than the wisest of our ancestors. But nothing was given to us: we paid the price, fully and validly, for everything.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.