Sunken Treasures From Ancient Egypt Are Now on Display in France

The Arab World Institute in Paris shows off 250 artifacts once lost underwater

For seven years, archaeologists have been unearthing artifacts dating back to ancient Egypt that were buried, until recently, at the bottom of the Mediterranean—and those treasures are now on display at a cultural institute in Paris.

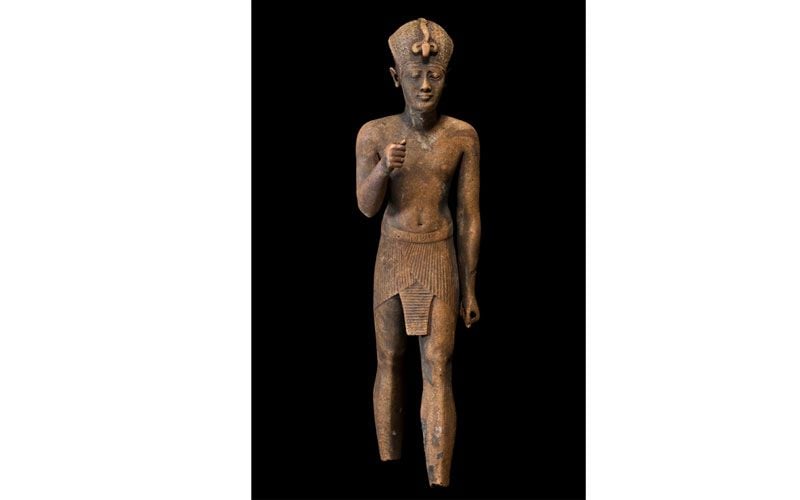

In an exhibit called “Osiris, Sunken Mysteries of Egypt,” the Arab World Institute is revealing 250 objects from underwater excavations conducted by archaeologist Franck Goddio, the founder and president of the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology. The exhibition also includes 40 pieces on loan from Egyptian museums, some of which are leaving the country for the first time.

The underwater artifacts come from the ancient cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus, which are now submerged off the coast of the Bay of Aboukir near Alexandria. These once-prosperous cities, writes the Guardian, “were almost erased from mankind’s memory after sinking beneath the waves in the 8th century AD following cataclysmic natural disasters including an earthquake and tidal waves.” In 1996, Goddio launched a collaboration with the Egyptian Ministry for Antiquities to survey and map the submerged land beneath the bay. That led to the re-discovery of the city of Canopus in 1997 and the nearby city of Thonis-Heracleion in 2000. Archeologists estimate that only one or two percent of what’s buried beneath the cities has been excavataed.

The exhibit takes its name from the legend of Osiris. Osiris, the story goes, was killed and cut into pieces by his brother Seth. Isis, Osiris’s sister-wife, “magically restored his body, brought him back to life and conceived their son Horus,” as the institute explains. Afterward, Osiris became the master of the afterlife—and his son Horus, after defeating Seth, his father’s brother and killer, “received Egypt as his inheritance.” The myth was celebrated in ancient times through an annual religious celebration in some parts of Egypt, including Canopus and Thonis-Heracleion.

Goddio and his team have found items that appear to be directly related to the Osiris ceremonies, including monuments, statues, ritual instruments, cult offerings and testimonies of celebrations. According to text they found inscribed on a stela—a stone slab or column bearing a commemorative inscription—the ceremonies “culminated in a long water procession, transporting Osiris along canals from the temple of Amun-Gereb in Thonis-Heracleion to his shrine in the city of Canopus.” The exhibit, which opened September 8 and will continue through January 31, 2016, shows visitors what these ancient annual traditions entailed, and offers a glimpse at a culture now lost beneath the sea.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/michele-lent-hirsch.jpg)