This Is the Wedding Dress Capital of the World

In Suzhou, China, step inside one of the world’s largest silk factories and see where wedding dresses come from

Welcome to Suzhou, China, the city of silk. Here, a large portion of the world’s silk is produced—and, according the the BBC, as many as 80 percent of the world’s wedding dresses. Suzhou has been one of China’s silk capitals for nearly the entire history of the fabric’s production, and, in recent years, a destination for soon-to-be-brides from the world over.

The idea of making silk stems from Chinese ingenuity, though the exact history of the practice is the stuff of legend. It’s said that about 6,000 years ago, Lady Hsi-Lin-Shih—the wife of Yellow Emperor Huangdi—was sitting under a mulberry tree in her garden drinking tea. A cocoon fell from the tree into her cup, and she was able to unravel the wet pod into a single strong thread. She went on to invent the loom and taught the locals how to raise silkworms for silk production. Archaeological sites along the Yangzi River have revealed ancient spinning tools and silk thread and fabric dating back to 7,000 BC.

For nearly 3,000 years, the Chinese kept silk-making processes a closely guarded secret, with leaks to the outside world punishable by death. Silk was obtained in other countries by way of the Silk Road, which began in eastern China and reached the Mediterranean Sea. Eventually, a group of Chinese immigrants settled in Korea and brought with them silk-making knowledge, and the practice began to emerge outside its country of origin. Suzhou, though, remained an epicenter of silk production, producing high quality silk in staggering amounts—and that continues to this day.

Making silk is not as quaint as it once was—pulling apart a tea-soaked cocoon under a mulberry tree—but it follows basically the same process. The biggest silk factory in China is in Suzhou, the Suzhou No. 1 Silk Factory founded in 1926. They’ve automated the silk-making process as much as possible, though workers have a hand in every step of the process, producing a truly handmade silk product. Because silkworms exclusively eat mulberry leaves, the factory has a small mulberry plantation. The silkworms feed on the leaves until they are large enough to spin a cocoon around themselves. Normally, they would emerge from the cocoon and become a moth—but in silk, the moths inside are destroyed before they have a chance to break through and cut the silk strand used to make the cocoon.

At this point, the cocoons are collected and sorted by a grading system. White and glossy ones of uniform thickness are the first choice and are used for creating silk thread. Twin cocoons, where two silkworms spun their cocoons together, are used for making silk quilts at the factory. Any other cocoons—yellowed or spotted ones—are sorted and removed. (The discarded moths are then used in cosmetic products.)

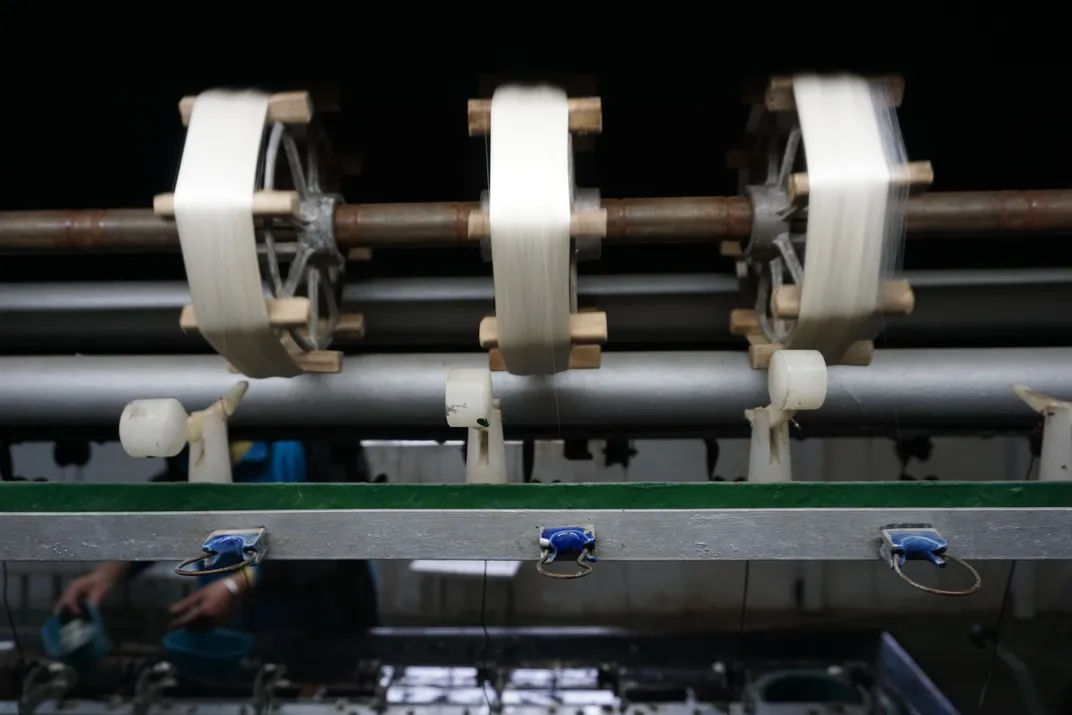

Next, the cocoons are boiled to dissolve the sericin, the gummy substance holding the cocoon together, so the thread can be easily unwound. The thread is then reeled into an initial ball, and re-reeled by a machine to remove any moisture left in the silk from the boiling process. A single cocoon can produce about 3,300 feet of silk thread. At the factory, 8,000 double cocoons are used to make a single quilt.

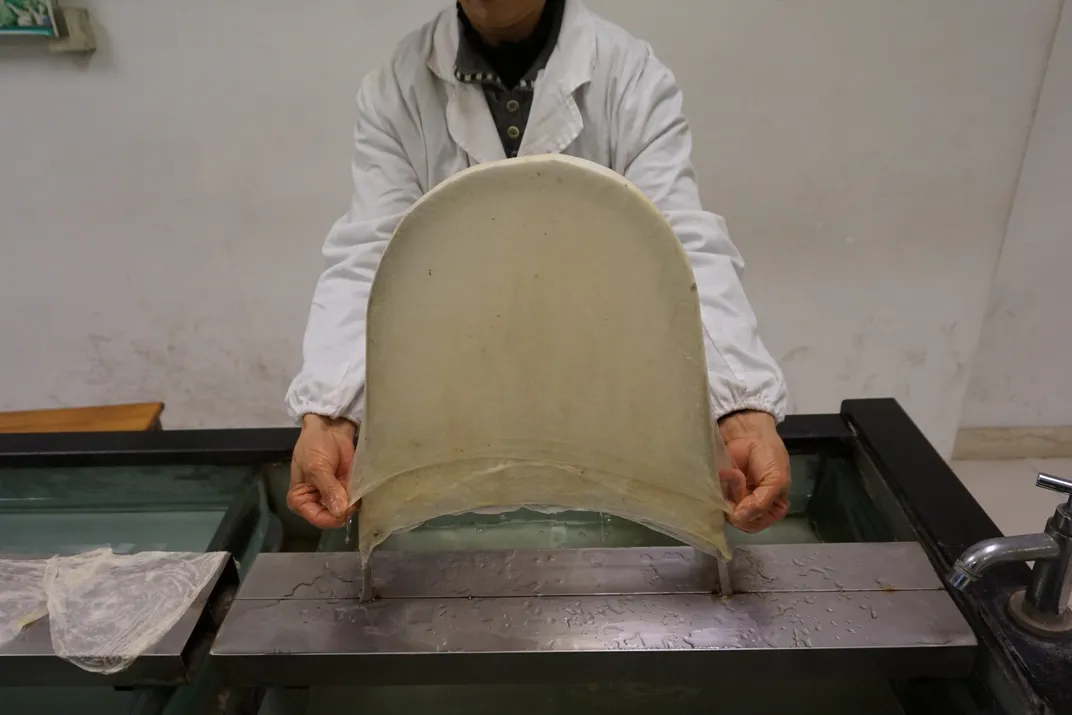

Visitors to the Suzhou No. 1 Silk Factory will tour the facility from mulberry plantation to finished silk product, exploring and observing each step in the process. There’s a display of working 100-year-old automated looms behind glass, all of which are making elaborate silk fabric in the old style. And near the end of the tour, just before the extensive gift shop replicating an ancient silk market, guests can try their hands at making a quilt themselves. With the help of workers or other guests, everyone grabs a bundle of silk from one corner and stretches it as far as possible without breaking it, setting it down atop hundreds of other layers of the same stretched silk. This pile will eventually be sewn into a silk quilt. You won’t be able to buy it that day, but you can officially say that somewhere in the world, someone owns a quilt you helped make by hand.

After leaving the factory, pop in to one of the over 1,000 wedding dress shops that line the streets near Huqiu, or Tiger Hill, to see the silk come to life in a dazzling display of designs.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)