Switzerland’s Historic Bunkers Get a New Lease on Life

As the shadow of war fades, the country’s former fallout shelters now house everything from museums to cheese factories

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d2/9d/d29d8686-30ed-4936-8652-f4b9c3b2f4fd/energie_02.jpg)

Switzerland hasn’t fought in a war in well over two centuries—but war shaped a hidden facet of the famously neutral country. In the 20th century, Switzerland had more bunkers than chocolate shops or banks combined. At one point, it contained an estimated 300,000 fallout shelters, with enough space to provide shelter for all of its eight million residents.

Fortified with thick cement walls, the bunkers were a way for the Swiss government to protect its citizens against a possible attack during World War II. Since the country sits between Germany and Italy, fears of a possible invasion were high as the Axis countries set their sights on using the alpine region as a passageway. In response, the Swiss government fortified its mountainous borders in what has been dubbed the “National Redoubt.”

But the bunkers far outlasted World War II. When the war ended in 1945, the Swiss government continued its defense strategy into the Cold War, and the bunkers served as protection against a possible Soviet attack. Bunkers weren’t luxuries for the country’s wealthy residents: They were mandatory. By 1963, Swiss law required that all new buildings provide protective shelters, resulting in a country pockmarked with shelters. One town, Faulensee, located 25 miles south of Bern, even cleverly disguised its Cold War-era bunkers to look like farmhouses to fool would-be bombers and dissuade possible aerial attacks. Many of the country’s largest military fortresses remained top secret, even into the 21st century.

“In 2001, someone tried to break into Sasso da Pigna [an artillery fort built into the side of St. Gotthard mountain], so the government was forced to declassify it; now it’s a museum,” Tom Markwalder, chief of marketing and sales for Sasso San Gottardo museum, tells Smithsonian.com. “That’s one reason why Swiss residents are so interested in seeing these massive forts up close—for years, they didn’t even know they existed.”

Today, bunkers are still required by Swiss law, though members of the parliament have recently tried (and failed) to overturn the rule. Thousands of bunkers still rest unused beneath Switzerland’s soil. But as they become declassified one by one, they’ve been given a new lease on life. Switzerland’s bunkers have now become hotels, museums and other attractions that make good use of the country’s strangely obsolete shelters. Here are a few that are worth a visit:

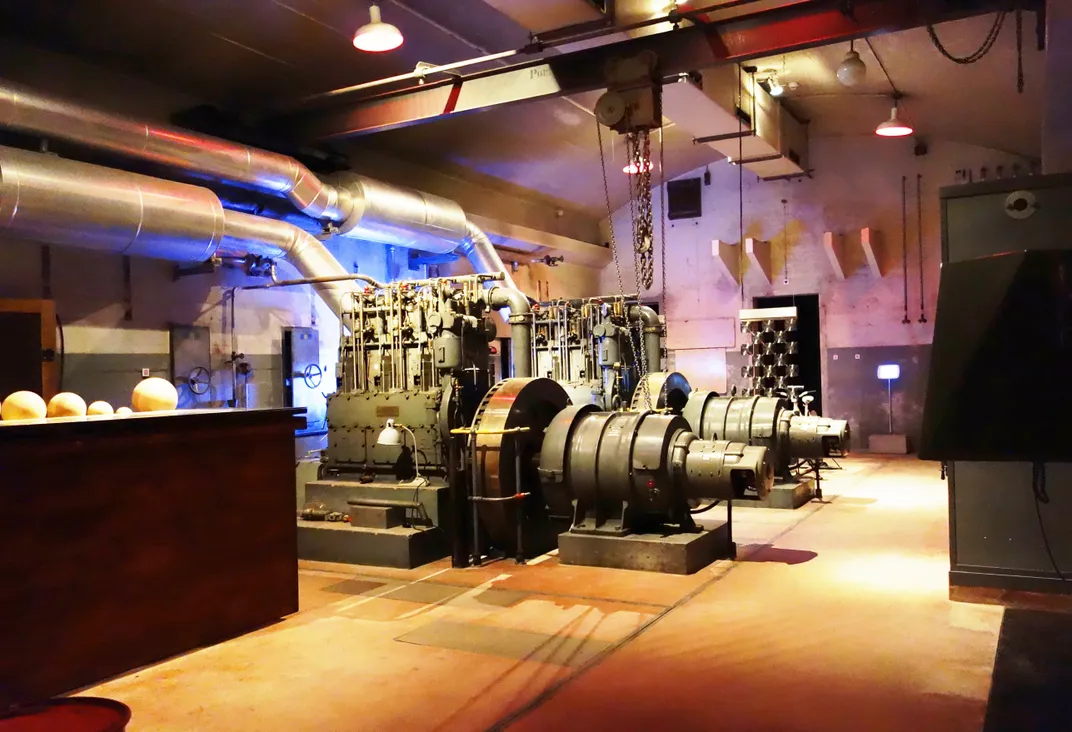

Sasso San Gottardo Museum (Airolo)

Embedded into the side of St. Gotthard Mountain, Sasso San Gottardo was once a super-secret fortress. Built between 1941 and 1945 as protection during World War II, the rock-fortified fort could house up to 420 men and had the capacity to store enough food, water and ammunition to be completely self-sufficient for several months. Frozen in time, the fort is now a museum. Visitors can see the underground complex as it was when it was fully operational, complete with two gun batteries, two bunker cannons and a full garrison along with a crew canteen, sleeping quarters and fire control centers. The museum also includes themed exhibits focused on subjects like mountain crystals and renewable energy.

Hotel la Claustra (Airolo) and Null Stern (Teufen)

Why hunker down in a bunker when you could luxuriate in one instead? Switzerland’s bunker hotels bring a bit of relaxation to the old shelters. Located an hour south of Lucerne and housed inside a former military bunker buried deep into the side of St. Gotthard Mountain, is one standout. Hotel la Claustra is a maze of cavernous hallways one would expect to find in a bunker, but with unexpected touches, like an indoor Jacuzzi and a restaurant.

Another bunker-bound hotel is Null Stern, a one-time pop-up hotel that’s now been converted to a museum. During its one-year run, the self-proclaimed “zero-star hotel” offered communal rooms for $25 per night with no windows and no room service; hot water was not guaranteed. Museum guests can now tour its “second check-in” by accessing the building via a manhole cover—the same way one would have gotten into the shelter if the country had ever been under attack.

Seiler Käserei (Sarnen)

Located more than 650 feet beneath Giswil Mountain in central Switzerland, Seiler Käserei AG, a cheese manufacturer, keeps row upon row of Raclette cheese aging in a former ammunition bunker. At any given time, 90,000 wheels of this semi-firm cow’s milk cheese are aging on wooden panels that once housed weaponry. The consistent temperature and humidity—plus the bunker’s thick walls, which are a mix of dolomite, flysch and chalk—make for perfect cheese-ripening conditions. The aging rooms are unfortunately off limits, but visitors can sample the final products at the cheese shop upstairs.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/86/7a86f285-b693-4474-aea6-e836bce8f18d/42-51759246.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/37/18373941-6d34-4631-898f-99fc3855646f/42-51759236.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/1b/681b376e-02e2-4664-bbae-f7dc53787cb6/aussenansicht_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/7c/7b7c3d47-5708-48e5-8bab-613eb364ac41/historische_festung_unterkunft.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/91/aa/91aa9e19-863d-4ac9-b45b-df72d69cf122/stollen_schacht_03.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/bd/37bd5d6f-9337-4033-ab86-eb4ffe487aca/ubersichtsplan_satellitenaufnahme.jpg)