Throughout history, people have turned to art in times of strife. American landscape painter Winslow Homer's later work is perceived to be a reaction to what he witnessed during the Civil War. Photographer Alice Austen created a whole series on immigrants coming into New York in the 1890s and being quarantined before they could enter Ellis Island. And, of course, this is evident in the present time, with coronavirus street art and murals memorializing George Floyd springing up around the world.

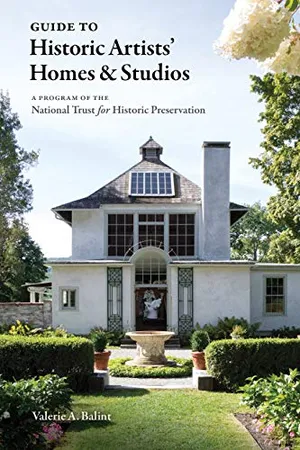

“In times like this, people do turn to these communal expressions of being human,” says Valerie Balint, author of Guide to Historic Artists' Homes & Studios, the new guidebook for the 44 site museums in the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Historic Artists’ Home and Studios program. “People look to the specific creative voice of humanity at times when other aspects of humanity are being challenged, and certainly artists who are producing in any one of those moments can't help but be impacted by that.”

Balint’s book offers an inside view of the homes and studios of American artists throughout history. Readers can imagine themselves walking through the living room of Weir Farm, the Connecticut home of the grand patriarch of American impressionism, Julian Alden Weir. They can explore the chaotic studio floor at the East Hampton, New York house where Jackson Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner, lived from 1945 until their deaths in 1956 and 1984, respectively. Readers can inspect the thousands of tiles lining the walls at Henry Chapman Mercer’s Fonthill Castle in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, or take in the statuary of Elisabet Ney’s self-designed sculpture studio in Austin, Texas.

Historic Artists' Homes and Studios: A Guide

From the desert vistas of Georgia O'Keeffe's New Mexico ranch to Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner's Hamptons cottage, step into the homes and studios of illustrious American artists and witness creativity in the making.

Through the book, it becomes apparent how the personal spaces of these artists impacted their work, potentially giving an idea of how we can embrace our own spaces as we stay home more often than not.

“While we're at home, we are communing with our personal spaces on an extended basis in ways many of us have not done for years,” Balint says. “It's really interesting to examine, at this moment, the incredibly personal spaces where some of the most important visual minds and creatives of American culture did their work. [It’s interesting to examine] the choices they made in terms of location, type of house they wanted to be in, the type of space, and what they surrounded themselves with, and how that fostered these great pieces of art and artistic movements that we still feel connected to today. Seeing how the landscapes informed works of art or how the artists themselves stretched into architectural and landscape practice beyond the confines of the picture frame really makes us remember that creative spirit is limitless. It humanizes these great geniuses of art, and reminds us that creativity resides in all of us.”

Armchair travel to the following American artists’ homes and studios through Balint's book, and then check out the virtual tours available for each site.

Thomas Hart Benton State Historic Site; Kansas City, Missouri

Large-scale muralist and painter Thomas Hart Benton lived in this limestone home, built in 1903 by architect George Mathews, with his family until his death in 1975. Benton worked in the carriage barn behind the house, where he spent the majority of his days painting. It was here he created one of his most famous works, A Social History of the State of Missouri, which is on display in Missouri's state capitol building. Benton died in his studio; he always returned to the house for dinner with his family, and one night, he returned to the studio to sign his latest (and last) piece, but collapsed and died before he could. Rita Benton, his wife, died only 11 weeks later, and the house and studio have remained the same ever since, per her wishes.

“We could see ourselves tinkling on the piano and grabbing a drink off of the bar cart in the dining room,” Balint says. “But when you're in the studio, you see all the different parts of process that need to go into making a really large-scale mural. Because of all the detritus that's there, you can actually see this is a very complex process.”

C-SPAN offers a video tour of Benton's home and studio, led by site administrator Steve Sitton. You'll also discover a bit about Benton's personal life.

Mercer Museum and Fonthill Castle; Doylestown, Pennsylvania

Henry Chapman Mercer’s concrete home and studio, constructed between 1908 and 1912, was of the tilemaker and archaeologist’s own design. Though inspired by European buildings the artist discovered during travels while he was younger, the building completely flouts standard construction methods of the time it was built.

“He just decided he was going to create a concrete castle in the image that he wanted to do it, which meant that he created a new way to use this material,” Balint says. “He completely abandoned any typical ways of planning for an architectural space. He actually just made little models of rooms and then stuck them together. That’s why the outside looks really weird and irregular. So often in architecture, you consider the exterior of the building. But Mercer really cared about how his rooms were going to be in relationship to each other, and how that would all fit together externally was just not as important to him.”

Inside, the home reflects the chaotic nature of its design through the thousands of tiles he used to adorn the walls, ceiling and floors. Mercer created tiles for specific themed rooms, like pink and blue tiles in the Columbus Room designed to reflect Columbus’ voyages and the native people of the places he landed. The 44-room castle is also lined with Mercer’s massive library and ceramics collection.

This three-minute video tour walks you through Fonthill Castle, sharing information about Mercer and the art decorating the walls inside.

Alice Austen House; Staten Island, New York

Photographer Alice Austen lived a privileged life, but also one that didn’t conform to modern times. Photography wasn’t considered a suitable profession for a woman; however, her family was wealthy enough that she didn’t need to live off just her earnings. She often shocked society when she donned her corset and bicycled into New York City to capture images of life there, from shoeshine boys to quarantined immigrants. She lived with her partner, Gertrude Tate, in the family home (where she had a small darkroom in an upstairs closet and had to wash her prints in the well outside), even though both their families disapproved of the relationship.

“The Alice Austen House is a nationally-designated LGBTQ site, and I think it offers members of that community a touchstone to go to, to understand the creative practice of a person who was trying to forge her own way within the social conventions and artistic conventions of her time,” Balint says. “She managed to live a life on her terms and created work that was interesting and unique.”

That being said, Austen’s house was typical for the time period, a 1700s Dutch cottage with Victorian and Gothic Revival elements added by her grandfather in 1844. Austen lost everything she owned, including the house, in the 1929 stock market crash. Her family wouldn’t allow her to legally live with Tate afterwards, so she intentionally stayed impoverished and moved into a local poor house where Tate often visited her. Austen died in 1952, and was again denied her wishes to be with Tate—she was buried in the family plot instead of together with her partner.

The Alice Austen House created this virtual tour on Google Expeditions, allowing viewers to walk through the home and overlay historical images onto the modern setting.

Elizabet Ney Museum; Austin, Texas

When sculptor Elisabet Ney built her limestone castle home and studio—at once Texas’ first artist studio and first art museum—in 1892, she was in her 50s and had already reinvented her life several times. She began her career among the German elite, friend to royals and war heroes and working out of a studio in the German royal court. She and her husband, Edmund Montgomery, came to the U.S. in 1871 to escape political turmoil and get medical care for Montgomery. They first lived on a cotton plantation in Texas, where Ney quit sculpting to run the plantation, raise her two children and be a leader in the Texas women’s rights movement.

When her surviving child was grown and out of the house, she built her studio and reclaimed a career as a sculptor. Some of her first commissions were sculptures for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and her masterpiece—Lady Macbeth—is on display at Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“This is a woman who lived nine lives,” Balint says. “She's an incredibly complex person. She basically built her studio to create an artistic enclave. She would hold studio salons right out by the lake. Austin is really known for being an artistic community, and she is the embodiment of what Austin represents. She helped forge it.”

Take a video tour of Elisabet Ney's studio and explore her sculptures on YouTube, led by the museum's curator Oliver Franklin.

Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center; East Hampton, New York

About a week and a half after getting married in 1945, abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner moved into a secluded cedar-shingle home built in 1879. Initially, Pollock painted in an upstairs bedroom while Krasner worked in the back parlor. But Pollock eventually moved his studio out to the barn, where the chaotic marks of his work remain splashed on the floor today. After Pollock’s death in 1956, Krasner moved into the barn studio, and today the walls still echo with the huge arching movements of her painting. The detritus of their work in the barn makes the building itself almost like stepping into a joint Pollock and Krasner painting.

“There are very few places you can go where you can understand process,” Balint says. “The house is so modest, and the studio is so modest, and there's this beautiful bucolic view out to the marshland and the creek. Pollock and Krasner both said they were inspired by this environment. And then you go into the studio, and you look down at the floor, and you look up at the walls, and you just understand being in the process. When you go to the studio, your understanding of the physicality of the process is changed through that experience.”

This YouTube virtual tour of Pollock and Krasner's home and studio, led by site director Helen A. Harrison, describes the history of the site, the artists' styles, and how the residence changed when it became a museum.

Winslow Homer House; Scarborough, Maine

In 1883, after gaining fame with oil paintings, watercolors and Civil War illustrations in Harper’s Weekly, painter Winslow Homer gave up urban life in New York City and moved to a coastal retreat in Maine, where he established his home and studio in a two-story Shingle Style carriage barn. Here, Homer dramatically shifted his work as well, from detailed illustrations to pieces reflecting the environment where he lived and worked.

“Works by Homer evoke such emotion for people,” Balint says. “And when you stand in the home, your sense of why you feel what you feel when you look at one of those paintings becomes even more imprinted upon you. You understand suddenly why that type of painting causes a reaction. You can see how a particular view and a particular environment can pull upon an individual soul and their desire to then somehow capture that for others.”

Homer lived a simple life in Maine, though taking time to travel regularly. He didn’t have running water or electricity, and relied on a fireplace for heat. His main goal was to focus on his work and the surrounding environs, leading him to create masterpieces like Weatherbeaten, an 1894 painting of a crashing ocean scene that’s now on display in the Portland Museum of Art.

This YouTube tour through Winslow Homer's studio speaks to artifacts, his career in New York before arriving in Maine, and his personal life.

Weir Farm; Wilton, Connecticut

American impressionism takes hold at Weir Farm, a home and studio enclave purchased in 1882 by Julian Alden Weir, a pioneer in the style. The 153-acre farm saw three generations of Impressionist work conducted on the premises, not just by Weir but also by his daughter, Dorothy Weir Young, and her husband, sculptor Mahonri Mackintosh Young, and artists Doris and Sperry Andrews, who bought part of the property after befriending the Youngs. Today, the farm and its picturesque red buildings are one of three major sites devoted to American Impressionism throughout history.

“Because it's multi-generational, you see the kind of studio a painter needs and wants, and then a hop, skip and a jump away is the type of very large studio that a sculptor needs,” Balint says. “You get to understand what the needs are of the different types of art practice in a really great way. Weir Farm is such a representation of what we, as Americans, think of when we think of our tie to the land—something that starts as a family farm and this beautiful pastoralness, and then all these interesting things come together about how we look at land in our culture.”

Follow along with this YouTube video tour to learn more about Weir Farm, its past residents, and the life and history of J. Alden Weir.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/2c/752c2ac1-b6cc-4450-b434-1f9bad02bd62/pollock_krasner_house-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4f/c2/4fc2c407-60a5-40fc-86fd-1975aaa41f7e/pollock_krasner_house-header.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)