Would You Like Some Salt and Pepper? How About 80,000 Shakers’ Worth?

Over the course of just a couple of decades, the Ludden family has amassed enough novelty shakers to fill two museums

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Salt-and-Pepper-Museum-Saltshaker-silverware-631.jpg)

The next time you knock over a salt shaker and throw a pinch of the spilled grains over your left shoulder to ward off bad luck, bear in mind that at one time they would have formed part of someone’s wages.

It’s amazing the things you learn when you least expect it. I’m getting an in-depth lecture about the world of salt, salt and pepper shakers, and salt cellars from Andrea Ludden, her son, Alex, and her daughter, Andrea, at their Museum of Salt and Pepper Shakers in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. And jolly interesting it is.

Far from being just a wacky obsession by a Belgian lady with a fetish for salt shakers, Andrea Ludden’s collection of over 40,000 pairs (half in the family museum in Gatlinburg and half in its new museum in Guadalest, in eastern Spain), started completely by chance, when Andrea bought a pepper mill at a garage sale in the mid-1980s.

It didn’t work, so she bought a couple more. “I used to stand them on the window ledge of my kitchen, and neighbors thought I was building a collection. Nothing could have been further from my mind!” They started bringing her new ones, and eventually, she says, “I had about 14,000 on shelves all over the house, even in the bedrooms.” That’s when her husband, Rolf, told her, “‘Andrea, you either find somewhere to put these things or it’s a divorce!’ So we decided to create a museum.”

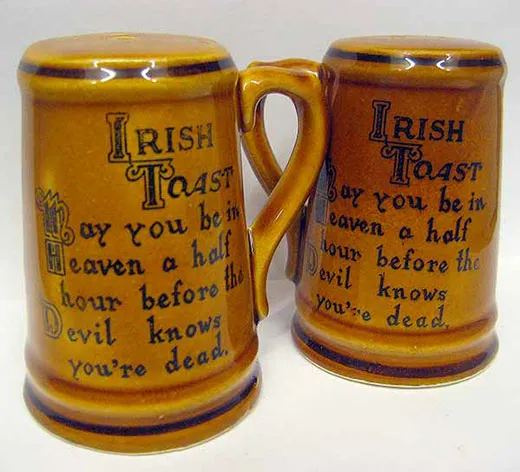

Wander around the museum and you’ll find it hard to believe that the 20,000 pairs of shakers—fat chefs, ruby red tomatoes, guardsmen in bear skins, Santa’s feet sticking from a chimney, pistols and potatoes, a copy of the salt-and-pepper-shaker cuff links worn by Lady Diana—have any reason for being together other than as someone’s idea of being collectibles, but they do.

An archaeologist by training, Andrea spent many years working in South America, where her main interest had been in how people traveled and communicated. When she and her family moved to the United States, she couldn’t find work in her field so she turned her attention to social anthropology, studying everyday life since the early years of the 20th century as seen through her growing collection of salt and pepper shakers.

“It’s often by looking at the apparently more mundane articles in everyday life that you can build up a broad picture of a specific period,” Andrea says. “There’s almost nothing you can imagine that hasn’t been copied as a salt and pepper shaker, and many of them reflect the designs, the colors and the preoccupations of the period.”

Salt shakers came into existence in the 1920s, she says. Previously, salt was typically served in a small bowl or container (the original salt cellar), usually with a spoon, because it had a tendency to attract moisture and become lumpy. Then, Chicago-based Morton Salt introduced magnesium carbonate to its product, which prevented caking and made it possible to pour salt from a sealed container. Pepper never suffered from the same susceptibility to dampness and, like salt, had also been served from a small container. But as it was habit to serve salt and pepper together, they became a pair, usually the salt shaker with only one hole and the pepper shaker with two or three.

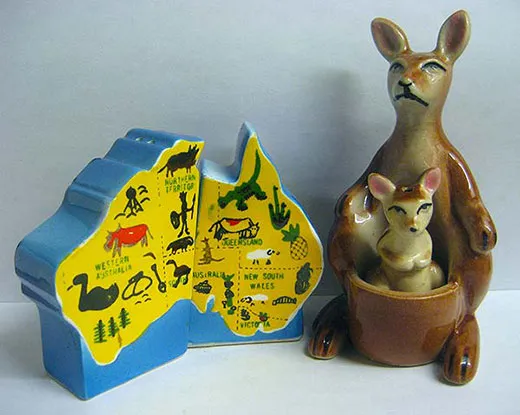

Morton’s development may have been the beginning of the salt and pepper shaker, but it was the automobile that led to its becoming a collectible item, says Alex. “It was because people could travel more freely, either for work or on vacation that the souvenir industry came about. Salt and pepper shakers were cheap, easy to carry and colorful, and made ideal gifts.”

“Imagine you lived in an isolated village somewhere,” he continues, “and your son or daughter brought you a set in the shape of the Golden Gate Bridge when they came on their annual visit home. It wouldn’t get used, it would be carefully kept as a decorative item. That’s how, in the main, many of the early collections began.”

Among the earliest producers of salt and pepper shakers was the German fine pottery maker Goebel, which introduced its first three sets in 1925. (Today its Hummel shakers, introduced in 1935, are highly collectible.) Ironically, it was the Great Depression of the 1930s that gave a major boost to the popularity of salt and pepper shakers as both a household and collectible item. Ceramics producers worldwide were forced to restrict production and concentrate on lower-priced items; an obvious product was the salt and pepper shaker. Bright and cheery, it could be bought for a few cents at most local hardware stores.

Soon other ceramics companies got into the act. Japanese firms had a large share of the market from the late 1920s through the 1930s, as well as from the late 1940s through the 1950s. (Production was halted during World War II.) The shakers they produced in the postwar years, labeled “Made in occupied Japan,” or simply “Occupied Japan,” are extremely rare and highly sought after.

In the 1950s and ’60s, companies began producing salt and pepper shakers made from plastic. Plastic then was fragile, so fewer of these examples exist, making them extremely valuable. “I love the plastics,” says daughter Andrea as she walks me around the museum. “They were the first ones that could have some sort of mechanism, and one of my favorites is a lawn mower with the salt and pepper shakers in the shape of the pistons.” When the driver pushed the mower, the pistons went up and down.

At first glance, the museum seems bright and happy, if a bit haphazard. But the displays are actually well thought out and organized, especially considering the many models on display.

“It’s almost impossible to categorize them,” the younger Andrea said, “because you can work by style, age, subject matter, color, etc., but we try and do it to combine all these elements at the same time. There are literally hundreds of themes, and in those themes there will be many colors, but Mom has a way of laying the displays out that are very highly planned, so that the colors within a theme are displayed together. For example,” she continues, “all the greens, yellows and reds of the vegetables are arranged in vertical rows, so you get bright color bands, but all the shakers are on the same theme. It’s a lot more complicated than it sounds because there are so many of them.”

A large number of the shaker sets are humorous in their design: an aspirin salt shaker and a martini-glass pepper shaker. And when displays are set up, there is sometimes an opportunity to create a visual joke.

“In one section,” says Andrea, “you see what looks like models of the Southwest U.S.—adobe houses of the style found in New Mexico, with cactus and cowboys and Indians. But behind them are two UFOs that have crashed and two aliens that glow in the dark. It’s the Roswell UFO crash in the 1940s.

It’s amazing how many of the shakers tell a tale that isn’t obvious to everyone. One of her favorites is a chef holding a cat in one hand and a cleaver in the other. “I always thought it was just a fun item,” says Andrea, “but my mom explained that it was very significant to older people who had been through the Depression and major wars. Food was short, but you still had to eat, so if a cat strayed by, it went into the pot and came out as ‘chicken surprise.’”

As I continue the tour, I’m absorbed by all the weird and wonderful shakers: Coca-Cola cans; Dolly Parton’s photo on a souvenir from Dollywood—“The Smokies most fun place”; Mickey and Minnie in chefs toques and aprons; the Beatles with the cropped hair and collarless jackets of their early days (George Harrison and John Lennon joined together as salt and Paul McCartney and Ringo Star as pepper); a turquoise TV with Lucy Arnaz and her neighbor, Ethel Mertz, on the screen (the salt) and a sofa with an “I love Lucy” heart-shaped cushion (the pepper); alligators with sunshades from Florida; bullfighters and bulls from Spain; kangaroos from Australia; a bobby and double-decker bus from London; before-and-after versions of Mount St. Helens made from the actual volcanic ash. There are also familiar ones: shakers your grandmother used to have, or you saw when you went on vacation somewhere, or you gave as a gift once.

“People come back over and over again and think that we are adding to the displays,” says Andrea, “but we aren’t. It’s just that they didn’t see them the first time around.”

The museum doesn’t display all the shakers it owns. But it does exhibit a few Aunt Gemima and Uncle Tom shakers, the cook and butler stereotypical characters from the 1950s, knowing some people might be offended by the negative portrayal of African-Americans. “They are part of the history of salt and pepper shakers, so we display them, but we do it discreetly,” she says. “You can’t change history by simply pretending it didn’t happen or ignoring it.”

But the museum draws the line at pornography. “There are a lot of pornographic models available,” says Andrea. “We’ve got about 60 pairs, ranging from a bit cheeky to quite explicit, but ours is a family museum, so we prefer not to put them on display.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.