The Devastating Costs of the Amazon Gold Rush

Spurred by rising global demand for the metal, miners are destroying invaluable rainforest in Peru’s Amazon basin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Amazon-Gold-rainforest-water-cannons-631.jpg)

It’s a few hours before dawn in the Peruvian rainforest, and five bare light bulbs hang from a wire above a 40-foot-deep pit. Gold miners, operating illegally, have worked in this chasm since 11 a.m. yesterday. Standing waist-deep in muddy water, they chew coca leaves to stave off exhaustion and hunger.

In the pit a minivan-size gasoline engine, set on a wooden cargo pallet, powers a pump, which siphons water from a nearby river. A man holding a flexible ribbed-plastic hose aims the water jet at the walls, tearing away chunks of earth and enlarging the pit every minute until it’s now about the size of six football fields laid side by side. The engine also drives an industrial vacuum pump. Another hose suctions the gold-fleck-laced soil torn loose by the water cannon.

At first light, workers hefting huge Stihl chain saws roar into action, cutting down trees that may be 1,200 years old. Red macaws and brilliant-feathered toucans take off, heading deeper into the rainforest. The chain saw crews also set fires, making way for more pits.

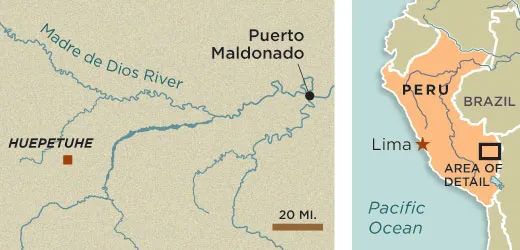

This gaping cavity is one of thousands being gouged today in the state of Madre de Dios at the base of the Andes—a region that is among the most biodiverse and, until recently, pristine environments in the world. All told, the Amazon River basin holds perhaps a quarter of the world’s terrestrial species; its trees are the engine of perhaps 15 percent of photosynthesis occurring on landmasses; and countless species, including plants and insects, have yet to be identified.

In Peru alone, while no one knows for certain the total acreage that has been ravaged, at least 64,000 acres—possibly much more—have been razed. The destruction is more absolute than that caused by ranching or logging, which accounts, at least for now, for vastly more rainforest loss. Not only are gold miners burning the forest, they are stripping away the surface of the earth, perhaps 50 feet down. At the same time, miners are contaminating rivers and streams, as mercury, used in separating gold, leaches into the watershed. Ultimately, the potent toxin, taken up by fish, enters the food chain.

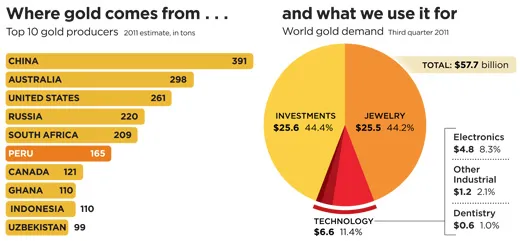

Gold today commands a staggering $1,700 an ounce, more than six times the price of a decade ago. The surge is attributable to demand by individual and institutional investors seeking a hedge against losses and also the insatiable appetite for luxury goods made from the precious metal. “Who is going to stop a poor man from Cuzco or Juliaca or Puno who earns $30 a month from going to Madre de Dios and starting to dig?” asks Antonio Brack Egg, formerly Peru’s minister of the environment. “Because if he gets two grams a day”—Brack Egg pauses and shrugs. “That’s the theme here.”

The new Peruvian gold-mining operations are expanding. The most recent data show that the rate of deforestation has increased sixfold from 2003 to 2009. “It’s relatively easy to get a permit to explore for gold,” says the Peruvian biologist Enrique Ortiz, an authority on rainforest management. “But once you find a suitable site for mining gold, then you have to get the actual permits. These require engineering specs, statements of environmental protection programs, plans for protection of indigenous people and for environmental remediation.” Miners circumvent this, he adds, by claiming they’re in the permitting process. Because of this evasion, Ortiz says, “They have a claim to the land but not much responsibility to it. Most of the mines here—estimates are between 90 or 98 percent of them in Madre de Dios state—are illegal.”

The Peruvian government has taken initial steps to shut down mining, targeting more than 100 relatively accessible operations along the region’s riverbanks. “There are strong signals from the government that they are serious about this,” says Ortiz. But the task is enormous: There may be as many as 30,000 illegal gold miners in Madre de Dios.

The pit that we visited that day is not far from Puerto Maldonado (pop. 25,000), capital of Madre de Dios, a center of Peru’s gold mining because of its proximity to the rainforest. In a supreme irony, the city has also become a locus of Peru’s thriving ecotourism industry, with inviting hotels, restaurants and guesthouses in the forest, at the threshold of a paradise where howler monkeys leap in tall hardwood trees and clouds of metallic blue morpho butterflies float in the breeze.

On our first morning in Puerto Maldonado, photographer Ron Haviv, Ortiz and I board a small wooden boat, or barca, and head up the nearby Madre de Dios River. For a few miles upstream, wood-frame houses can be glimpsed along heavily forested bluffs. Birds dart through the trees. Mist burns away on the tranquil, muddy-brown river.

Suddenly, as we round a bend, the trees are gone. Barren stretches of rock and cobblestone line the shore. Jungle is visible only in the distance.

“We are coming to the mining,” says Ortiz.

Ahead of us, nosed against the stony banks, countless dredge barges are anchored. Each is fitted with a roof for shade, a large motor on deck and a huge suction pipe running from the stern into the water. Silt and stones extracted from the river bottom are sprayed into a sluice positioned on the bow and angled onto shore. The sluice is lined with heavy synthetic matting, similar to indoor-outdoor carpet. As silt (the source of gold) is trapped in the matting, stones hurtle down the incline, crashing in great mounds on the banks. Thousands of rocky hillocks litter the shoreline.

As we pass one barge—its blue-painted steel hull faded by the intense sun—the crew members wave. We beach our barca and clamber over the stone-strewn shore toward the barge, moored along the bank. A man who appears to be in his 30s tells us that he has mined along the river for several years. He and his family own the barge. The entire clan, originally from Puerto Maldonado, lives aboard much of the time, bunking in handmade beds on deck beneath mosquito nets and eating from a galley kitchen run by his mother. The din from the dredging engine is deafening, as is the thunder of rocks tumbling into the sluice.

“Do you get a lot of gold?” I ask.

The miner nods. “Most days,” he says, “we get three, four ounces. Sometimes more. We split it.”

“How much is that a day?” I ask.

“About $70 most days, but sometimes as much as $600. Much, much more than many people back in the town make in a whole month. It’s hard work, though.” Princely though this renumeration may seem to the miner, it is only a fraction of the price an ounce of gold will command once it passes through the hands of countless middlemen.

Roughly 80 miles southwest of Puerto Maldonado, the gold rush boomtown of Huepetuhe lies at the foot of the Andes. It’s the summer of 2010. Muddy streets are pocked with puddles the size of small ponds. Pigs root everywhere. Boardwalks keep pedestrians—at least those not too muddy or inebriated to care—out of the slop. Makeshift wooden-plank structures, many on stilts, are roofed in patched corrugated metal. From their stalls, vendors sell everything from automobile piston rings to potato chips. There are rough little bars and open-air restaurants. Along the main street are dozens of shops where gold is assayed, weighed and bought.

Behind town, in the Huepetuhe River valley, virgin rainforest has been razed. “When I first came here, 46 years ago, I was 10 years old,” Nico Huaquisto, a resident, recalls. “The Huepetuhe River was maybe 12 feet wide and its water ran clear. Along the river’s edges, there was jungle all around. Now—just look.”

Today, Huaquisto is a very wealthy man. He stands at the edge of the 173-acre backhoe-dredged canyon that is his mine. Although he has a large house nearby, he spends most days and nights in a windowless shack next to his gold sluice. The sole concession to comfort is a cushioned armchair in the shade of a tiny porch. “I live up here most of the time,” he says, “because I need to watch the mine. Otherwise, people come here and steal.”

He is also the first to admit that he has obliterated as much of the upper Amazon jungle as anyone. “I have done everything within the law,” Huaquisto insists. “I have the concession permits. I pay my taxes. I live inside regulations for the use of liquid mercury. I pay my workers a fair wage, for which taxes are also paid.”

Yet Huaquisto acknowledges that illegal miners—essentially squatters—dominate the trade. The area surrounding town, he adds, is overrun with black-market operations. Law enforcement authorities, says Enrique Ortiz, “have decided that this zone of forest has already been sacrificed, that this is one place where mining can just happen ...as long as it remains somewhat contained.”

Huaquisto takes me to the edge of a cliff on his property and points downhill, where a series of collecting mats have been placed inside a narrow, eroded gully. Water flowing from Huaquisto’s sluice has cut this gash in the land. “All of those mats down there?” he says. “They’re not mine. That’s no longer my property. There are 25 or 30 illegal people down there, their mats trapping some of the gold my workers dig, gathering it illegally.”

Huaquisto’s mine is sobering in its scale. In the middle of a stony, barren plain that was once mountainous rainforest, two front-end loaders work 18 hours a day, digging up soil and depositing it in dump trucks. The trucks rumble to the top of the highest hill, where they empty their loads into a several hundred-foot-long sluice.

“As you dig, do you ever find anything else that’s interesting?” I ask.

“Yes,” Huaquisto says. “We often find ancient trees, long buried. Fossil trees.” He watches the next truck as it passes. “Four trucks make one circuit every 15 minutes. When they go faster, there are accidents. So that is the rule I have made: one trip every 15 minutes.”

I point out that this equals 16 dump-truck loads of rock, stone and soil every hour. “How much gold do you get?” I inquire.

“Every day?”

“Yes, every day.”

“Please remember,” Huaquisto says, “that about 30 to 40 percent of what I make is taken up by petroleum and the cost of pumping all the water. Plus, of course, the workers, who I pay a lot of overtime to every day. This is a very good job for a local person.”

“But how much do you get a day?”

“There are other costs, as well,” he goes on. “Environmental remediation. Social programs. Reforestation.”

After a long pause, he answers: After expenses, Huaquisto says, he nets between $30,000 and $40,000 a week.

By our second morning in Huepetuhe, after Ortiz, Haviv and I have interviewed gold buyers and liquid mercury sellers, shop owners and grocery clerks, the atmosphere begins to grow hostile. A miner stops and stares at us. “You’re going to f--- us,” the man says. “F--- you!” He continues down the street, turning back to shout more expletives. “We have machetes,” the man shouts. “I’m going to get my friends and come back for you. You stay there! Wait!”

A pit-scarred landscape near the outskirts of town is said to be one of the region’s largest and newest mining sites. Runaway excavation has created a desolate gold-mining plain, jutting into still-virgin rainforest. At a new settlement for the nomadic miners, a wooden bunkhouse, office, cantina and small telephone exchange have been erected. The outpost is surrounded by recently denuded and eroded hills.

As our drivers and guides enter the bunkhouse, hoping to get permission to look around and conduct interviews, two miners on a motorbike brake to a stop as I call out a greeting.

“How long have you been working here?” I ask.

“Five months,” one of them replies.

I gesture across the swath of destruction where rainforest once stood. “How long has this mine been here?”

The men look at me. “All of this is the same age,” one of them replies. “We have been here since the beginning. All of this is five months old.”

A manager of the operation grants us permission to conduct a few interviews, but in the end the only miner who cooperates is a 50-something, heavyset man with thick black hair. He declines to give his name. He comes from the Andean highlands, he tells us, where his family lives. He often works in Huepetuhe.

“The money is good,” he says. “I work. I go home.”

“Is this a good job?” I ask.

“No, but I have raised five children in this way. Two work in tourism. One is an accountant. Another has just finished business school and another is in business school. My children have moved past a job like this.”

At last, we get into our cars. Now, behind us, Huepetuhe is visible only as a wide slash of brown and gray inside mountainous green jungle.

Among the people trying to improve living and working conditions in the hellish, Hieronymus Bosch world of the gold fields are Oscar Guadalupe Zevallos and his wife, Ana Hurtado Abad, who run an organization that provides shelter and education for children and adolescents. The couple started the group Association Huarayo, named for the area’s indigenous people, 14 years ago. One of their first charges was a 12-year-old orphan named Walter who had been abandoned at a mine site. They adopted and raised him, and Walter is now a 21-year-old college student.

With children being sent alone to the gold fields, to be exploited as service workers, often in kitchens, Association Huarayo built a safe house where children could live and be cared for. “There are no other places where these young people can find safety,” Guadalupe says. “Our budget is low, but we survive thanks to the work of many, many volunteers.”

Two nights ago, he tells me, authorities from nearby mining settlements brought 20 girls between the ages of 13 and 17 to the safe house. “They just arrived,” Guadalupe says. “We are worried about feeding them all, housing them, finding them school.”

“What about their families?” I ask.

“Their families are gone a long time ago,” he replies. “Some are orphans. Many were taken and put into slavery or forced labor before they knew the name of their village.”

Guadalupe tells the story of a 10-year-old girl brought to them two years ago. Originally from the outskirts of the highland capital of Cuzco, she was from a family who had been tricked by a woman working for the gold mines. The woman told the girl’s parents, who were very poor and had other children to feed, that the daughter would be brought to Puerto Maldonado and given work as a baby sitter for a wealthy family. The girl would make a good income. She could send money home. The parents were given 20 Peruvian soles (about $7) to give up their daughter.

Instead, the girl was taken to a gold camp. “She was put into the process of becoming a slave,” Guadalupe says. “They made her wash dishes at first, for no money and only food, day and night, sleeping in the back of the restaurant. This life would break her down. She would soon be moved into prostitution. But she was rescued. Now she is with us.”

He shows me photographs of girls they are sheltering. The youngsters appear to be in their early teens, sitting at a large dining table, set with bowls containing salad and rice, platters of meat, and glasses of lemonade. The children are smiling. Guadalupe points out the girl from Cuzco, who has glossy jet-black hair and a small birthmark on her cheek.

“Does she want to go home? Back to her parents?” I ask.

“We have not found her family. They may have moved,” Guadalupe says. “At least she is no longer leading a life in the gold town. She is 12 years old, trapped between two worlds that have shown no care for her. What is she to do? What are we to do?”

Guadalupe stares into the distance.“With a little help, a little support, even the ones who were previously lost can make a positive contribution,” he says. “We maintain hope.”

On our way by car to Lamal, a gold-mining settlement roughly 60 miles west of Puerto Maldonado, we pull off the road into a kind of way station, the site of a restaurant. In the muddy parking area, drivers with motorbikes await paying passengers.

With motorbike headlights on, we take off on the 25-minute ride. It’s 4 a.m. A single track leads into impenetrable black jungle. We jolt along rickety wooden boardwalks elevated on wooden stilts above streams and swamps. At last we emerge onto muddy, deforested plains, passing skeletal wood huts near the trail, their plastic tarps removed when inhabitants moved on.

We pass a settlement of shops, bars and dormitories. At this hour, no one seems to be awake.

Then, in the distance, we hear the roar of engines, powering water cannons and dredge siphons. The stench of forest burned to ash hangs in the air. Towering trees, perhaps 150 feet tall, not yet sacrificed, can be glimpsed in the distance.

Then we reach the enormous pits, lit by strings of lights dangling across their gaping emptiness. Men stand in deep pools of turbid water, manning water cannons; another crew siphons displaced silt, rock and gravel.

My driver tells me that this particular pit is known as Number 23. During the next two hours, the destruction inside is relentless. The men never look up: They are focused on dislodging the soil, suctioning it, then dumping the slurry down a nearby sluice.

Finally, around 6:30, as light filters into the sky, men carrying gigantic chain saws—the cutting bars on each must be four or five feet long—enter the forest, walking around the edges of the holes. They go to work on the biggest trees.

The pit crews have finished digging. At 7 a.m., after giving the mats lining the sluice time to dry, the men fold them up, careful not to allow any muddy residue to ooze away. The laborers lug a dozen or so to an area near the bottom of the sluice. There, a square blue waterproof tarp lies on the ground, its edges enclosed by felled tree trunks, creating a shallow, makeshift pool perhaps 9 by 12 feet.

The men lay the mats, one at a time, in the pool, rinsing each repeatedly until—at last—all the gold-laced silt has been washed into the cache. The process takes close to an hour.

One of the workers who has emerged from the pit, a 20-year-old named Abel, seems approachable, despite his fatigue. He’s perhaps 5-foot-7 and thin, wearing a red-and-white T-shirt, blue double-knit shorts and knee-high plastic boots. “I have been here two years,” he tells me.

“Why do you stay?” I ask.

“We work at least 18 hours a day,” he says. “But you can make a lot of money. In another few years, if nothing happens to me, I can go back to my town, buy a nice house, buy a shop, work simply and relax for my life.”

As we are talking, women from the blue-tarp settlement behind us—back toward the road a half-mile or so—arrive with meals. They hand white plastic containers to the crew. Abel opens his, containing chicken-and-rice broth, yucca, hard-boiled eggs and roast chicken leg. He eats slowly.

“You said, ‘if nothing happens,’ you will go home. What do you mean?”

“Well,” Abel says, “there are a lot of accidents. The sides of the hole can fall away, can crush you.”

“Does this happen often?”

In the 30 or so pits here, Abel says, about four men die each week. On occasion, he adds, as many as seven have died in a single week. “Cave-ins at the edge of the hole are the things that take most men,” Abel says. “But also accidents. Things unexpected....” He lets the thought trail off. “Still, if you go slowly, it’s OK.”

“How much money can you make?”

“Usually,” he says, “about $70 to $120 a day. It depends.”

“And most people in your hometown, how much do they make?”

“In a month, about half of what I make in a day.”

Then he simply lies on his back in the mud, leans his head against the trunk of a felled tree, crosses his boots at the ankles and instantly goes to sleep, hands clasped over his chest.

A few feet away, a thick layer of sludge lies in the bottom of the pool. As workers prepare to separate gold from silt, the overseer of this particular pit, who is named Alipio, arrives. It’s 7:43 a.m. He will monitor the operation, to make sure that none of the gold in the pool is stolen by workers.

Alipio is friendly yet serious. Like all the men here, his face is chiseled by a life of hard labor. As the men collect the sludge inside the pool, using a stainless-steel bowl about 12 inches in diameter, he watches them closely.

Meanwhile, 150 yards away, the chain-saw-wielding crew fells trees with professional ferocity. Every few minutes, another jungle hardwood topples. The earth shakes.

After the workers empty the first loads of sludge into an open 55-gallon drum, they pour in a little water and two ounces or so of liquid mercury, a highly toxic substance known to cause a host of ill effects, notably neurological disorders. Another miner from the pit, who gives his name only as Hernan, steps into the drum. Now exposed directly to the poison, he works the mixture with his bare feet for five minutes, then climbs out. He grabs an empty stainless-steel bowl and dips it into the barrel, panning for gold. A few minutes later, a gleaming, gelatinous alloy, or amalgam, has formed. It is seductively striated, gold and mercury. He places it in a zip-lock bag and goes back for another load of silt.

After another hour, once that day’s sludge has been processed, the amalgam fills half the plastic pouch. Alipio, Haviv, Ortiz and I walk to the makeshift settlement of Lamal. There are bars here and, in one tent, a brothel. An abandoned hamlet we passed during the motorcycle ride also was called Lamal. The word, says Alipio, pointing at the barren soil, is based on the Portuguese for “the mud.”

Near a cantina and a few bunkhouses, we enter a blue-nylon tent containing only a propane-gas canister and a strange metallic contraption resembling a covered wok, set on a propane burner. Alipio removes the lid, dumps in about one-third the contents of the zip-lock bag, screws down the lid, turns on the gas and lights the burner under his gold cooker.

A few minutes later, Alipio turns off the propane and unscrews the lid. Inside sits a rounded chunk of 24-karat gold. It looks like a hard golden puddle. Using tongs, he lifts out the gold, examining it with a practiced air. “That’s about three ounces,” he announces. He sets it on the packed-earth floor in the tent, then begins the process again.

“How much will you earn for the three ounces of gold?” I ask.

“Well, I must pay everyone. Pay for fuel, food for the men, pay for the engine and dredge siphon...upkeep on the engine, the mercury...other things.”

“But how much?”

“We don’t get the same price for gold here as they pay on Wall Street. Or even in cities.”

Finally he shrugs. “I’d say, after all the pay and expenses, approximately $1,050.”

“And you’ll do three of those this morning?”

“Yes.”

“That’s an average morning?”

“Today was OK. Today was good.”

A few minutes later, he begins cooking his next batch.

Alipio mentions that recently the price of gold has fallen a bit. Because costs for mercury and fuel have increased, he says, he and his crews exist at the margin of profitability.

“What will happen,” I ask, “if the price of gold falls a lot, as it does from time to time?”

“We’ll see if that happens this time,” Alipio says.

“But if it does?”

We glance around at the wasteland that was rainforest, its handful of remaining trees, cache pools contaminated with liquid mercury, and bone-tired men risking death every day in the Amazon basin. Eventually, untold tons of mercury will seep into the rivers.

Alipio gazes out at the ruined landscape and its tent city. “If gold is no longer worth getting out of the earth here, the people will depart,” he says, gesturing across the tableau of ruin—mud, poisoned water, vanished trees. “And the world left behind here?” he asks. “What’s left will look like this.”

Donovan Webster lives in Charlottesville, Virginia. Photographer Ron Haviv is based in New York City.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Don4x5.tif)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Don4x5.tif)