The Great Battles of History, in Miniature

At a museum in Valencia, Spain, over one million toy soldiers stand at attention, prepared to reenact the wars that shaped the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Toy-Soldiers-Napoleonic-cavalry-charge-631.jpg)

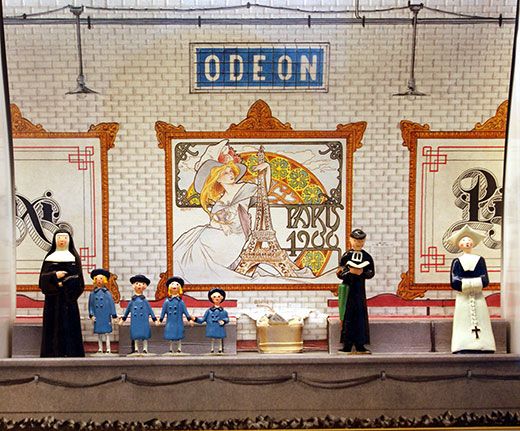

Tucked away on a shelf in a salon of a 17th-century palacio in Valencia, Spain, is a diorama of a room in the house of a 15th-century nobleman. In it a group of tiny figures, each no more than two inches tall, stand beside a wooden table on which rests a golden crucifix and a leather case with metal studs. The figure of a lady in a blue dress and crown is conversing with someone across the table, an elegantly dressed man in a maroon jacket, green trousers and leather gaiters, with a sheathed dagger hanging from his belt.

The scene depicts the moment Queen Isabella of Spain surrendered her jewels to a banker to provide funds for the building and equipping of the Niña, the Pinta and the Santa Maria, leading to Columbus’ discovery of the Americas. It is just one of many on view at the Museo de los Soldaditos de Plomo, the largest collection of toy soldiers and miniature figures in the world.

I’m sitting in the office of Alejandro Noguera, the director of the museum. Through the open door to my right are over 85,000 figures, with 12 times that amount stored away in boxes in buildings behind the museum. Noguera tells me that in 1941, his father received a set of toy Spanish soldiers from his father for his second birthday. That was the beginning of a vast private collection.

“I don’t remember a holiday as a boy that didn’t involve searching through shops and flea markets looking for toy soldiers,” says Noguera. “But as well as my father’s collection being a hobby, he also used it as instruction for myself and my brother and sister.” Noguera remembers using the metal soldiers in war games on the tennis court and in the gardens of the family’s country house as a small boy. “It was great fun,” he says, “and we used Second World War armies, with rules about diplomacy and economy, but it was also my father’s way to teach us about business, because if you know how to organize an army, you know how to organize a business, a library, almost anything.”

Noguera takes me into the museum, where I admire displays of marching soldiers that bring back fond memories of sitting in front of the living room fire as a small boy, organizing battles and bombings, through which most of my soldiers ended up headless and armless within weeks. He says the original idea for the museum was simply to display his father’s collection, but as he became more involved in the research behind both the making of the miniatures themselves and the stories they represented, he decided to take a different approach, thinking of a historic scene he’d like to present and then buying or commissioning the figures to create it. “My father thought that everything should be put on display, but apart from that being physically impossible because of the size of the collection, I thought it would be better to leave much more open space, and present the collection in a series of dioramas and large spectacular scenes, particularly the major battles.”

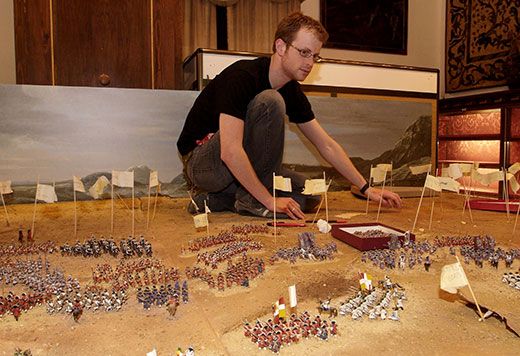

And you don’t get more spectacular than the 10,000-piece re-enactment of the Battle of Almansa, which took place April 25, 1707. The battle was a defining moment in European history, resulting in the Bourbon King Philip V wresting the crown of Spain from Archduke Carlos and ending centuries of rule by the Roman-Germanic Empire. The display doesn’t just include the soldiers in the battle, but also their wives and children, muleteers and “camp followers” (prostitutes), the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker—all people who were a part of every major battle in history until recent times.

I’m in awe as we walk around the museum, not just because of the breadth of the collection, which includes everything from lavish military displays and gore-filled battle scenes to ladies modeling the latest Chanel fashions and families frolicking on the beach, but also because of the incredible detail of the models and dioramas. That’s hardly surprising, given that Noguera is a historian and archaeologist. When you see hieroglyphics in the Egyptian scenes, you can be certain they are correct for the time the scene took place, partly because of the extensive research Egyptologists have done at such historic sites as Luxor, but also because Noguera spent three years studying the ancient writing system.

“I was walking past a diorama of the Roman emperor Tiberius a few weeks ago and saw some Afghan hounds,” says Noguera. “I wasn’t sure that was correct, but when I checked, it turned out that Alexander the Great had brought some to Rome after his invasion in 330 B.C.”

The craze for collecting toy soldiers began with the French in the 18th century. When Napoleon Bonaparte planned his military campaigns, he used models made by Lucotte, one of the top French toy soldier makers of the day, to show the positions of his armies. One day he handed a few of the figures over to his son to play with. Sycophantic courtiers did the same with their children, and before you knew it, everyone was collecting the soldiers.

But as far as Noguera is concerned, it’s the British who mastered the craft of sculpting miniatures. He shows me a tiny Egyptian chariot pulled by two black horses, with an archer with bow drawn riding alongside the charioteer, by the English maker Andrew Rose. “He was the best sculptor of soldiers ever,” says Noguera. “He had a complete affinity with the work, and his models are so refined that you can almost see the movement in the figures.” Noguera also ranks the firm Greenwood and Ball highly, calling it the Da Vinci of soldier painters. He shows me three of the figures, a guardsman and two Indian Army officers, painted in remarkable detail.

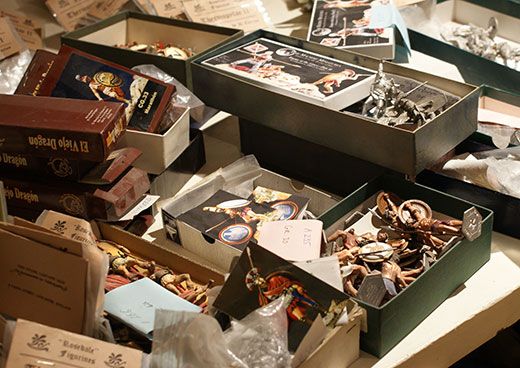

We leave the museum proper and enter the netherworld of storerooms that house the models that will one day fill the rooms of the palacio. Thousands upon thousands of boxes are piled in corridors, squirreled away under the building’s eaves, stacked on shelves and scattered across the floor. But despite the seeming disorder, almost every item is cataloged, and the curatorial staff knows exactly where everything is, be it a hussar from the Napoleonic period or an 1800s-era skiff for a leisurely sail on the Nile.

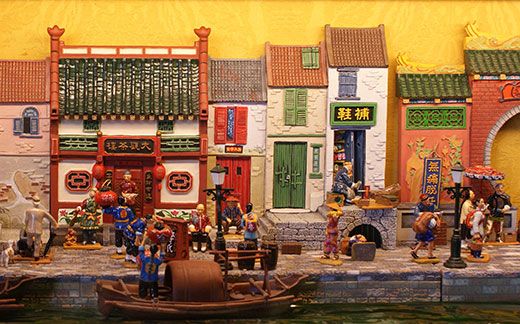

Each year the museum mounts a major exhibition based on a particular theme. “When we begin planning the exhibition, which usually takes about a year to put together, we look at what models we have and what is either in the public eye at the moment or is a significant historical event coming up,” say Noguera. “For 2011 we decided on ‘55 Days at Peking,’ based partly on the 1963 film of that name, but also because of the current interest in China as a major political and economic force.” (The 2012 theme, on view through June 2012, covers the Napoleonic Wars)

In 1901, the Righteous Fists of Harmony, better known as the Boxers, laid siege to the Legation District of Peking, the area in which all foreign nationals lived. They were incensed by the excesses of the foreign powers that controlled the city. For 55 days the Chinese government vacillated between killing the foreigners or seeking reconciliation. The equivocation cost the government dearly, when an alliance of the eight foreign nations with citizens held hostage in the Legation District sent 20,000 armed troops to Peking, defeated the Imperial Army and recaptured the city.

“This was the last colonial war in China,” says Noguera. It was the “Awakening of the giant, when China saw for herself that she could be a powerful nation, which we see much more so today. It resonates with the moment we are all living through.”

Noguera and his staff search the archives for pieces they will use. Some are in perfect condition, some will need restoration, and some will be bare metal needing complete repainting. The work is meticulous, with model makers and designers slowly bringing the exhibition to life, scrupulously making sure every last detail about the rebellion is accurate.

By the end of the 1990s the largest manufacturer of miniatures in the world was Spanish producer, Alymer, but this isn’t as voluminous as it sounds, as they only had fifteen employees. Most ‘factories’ were mom and pop affairs, one person doing the sculpting, the other the painting, and only male figures were produced. By this time the Noguera family were buying around 50 percent of the world’s production of toy soldiers and miniatures, including almost everything Alymer produced, and were having difficulty creating the dioramas they needed because of lack of female models.

“It would have been a bit difficult to create a diorama of the Rape of the Sabine women or a Roman bacchanalia before that,” says Noguera with a smile. “So we started the company Facan to make female miniatures, and also trees, park benches, houses and all the paraphernalia we needed that we couldn’t get elsewhere.”

“When most people look at a display in a museum such as ours they often forget that a lot of what they see wasn’t originally made simply as collectors items, they were toys,” says Noguera. “Some of the French soldiers used in the display were made by Lucotte in 1902, a year after the Boxer Rebellion, simply as toys for kids to play with.”

L’Iber, Museo de los Soldaditos de Plomo, Calle Caballeros 20-2, Valencia.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.