The House Where Darwin Lived

Home to the naturalist for 40 years, the estate near London was always evolving

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/House-of-Darwin-Down-House-631.jpg)

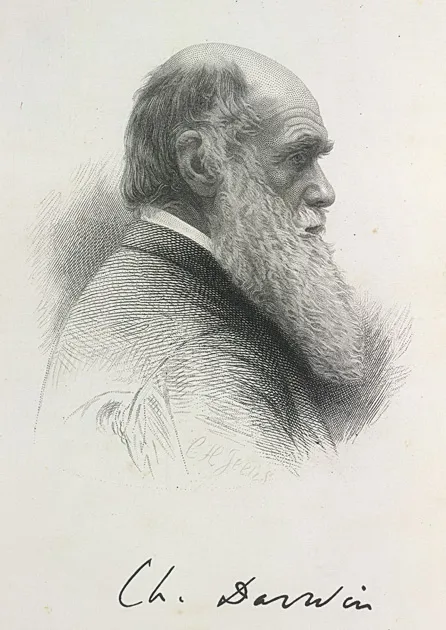

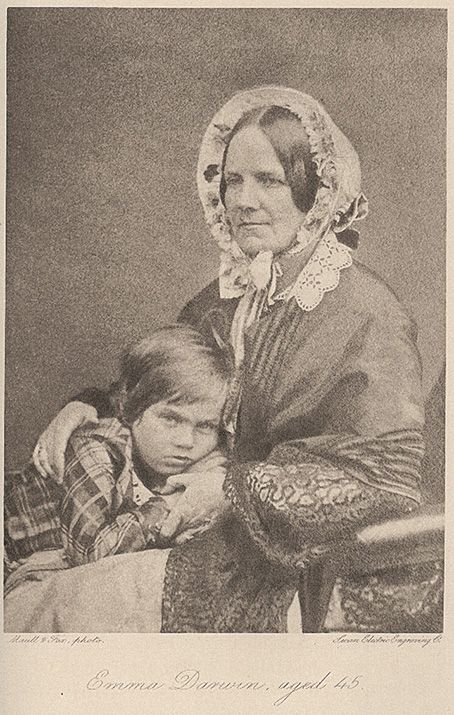

Charles Darwin lived with his wife, children and servants in Down House, a Georgian manor 15 miles south of London in the Kent countryside, for 40 years—from 1842 to 1882. Like all close-knit families, they did not just live in this house, they created a remarkable home here. Emma and Charles adapted Down House and the 20 or so acres of its grounds, extending the building and gardens continually, so they could nurture a large family and a community within it, built on routines, mutual respect, adaptation, tolerance, affection and good humor.

In his book Art Matters, the art theorist Peter de Bolla claims that we must attend to what paintings “know,” what knowledge they contain in themselves that is separate from what their makers might have known; coming back to visit Darwin’s house last fall, in rich autumnal sunshine, I wondered what Down House might know, not just about Darwin and his family but about kinship and community.

Once Emma died, in 1896, 14 years after her husband, the house was rented out to tenants and spent some time as a girls’ school, but from the late 1920s various attempts were made to preserve it as a monument to Darwin. An institution called English Heritage acquired Down House in 1996 and restored it; it is open to visitors year-round and now has a small museum, a shop and a parking lot. Though it was the home of a wealthy country squire, it was always a family house, not at all showy, and its curators have kept it that way. There’s a large hallway with cupboards built to store tennis rackets and boots and old manuscripts. Off it branch high-ceilinged family rooms: a billiards room, Darwin’s study, a drawing room, a dining room. Upstairs is a school room and bedrooms and, on the third floor, servants’ quarters. The high windows have solid-panel shutters that fold back into their frames, so the boundary between inside and outside seems permeable; trees and green are visible everywhere through glass; light pours in.

A few years after Darwin had established a life here and become the father of the first four of his ten children, he wrote to his friend Robert FitzRoy, captain of the research vessel HMS Beagle, with delight: “My life goes on like Clockwork, and I am fixed on the spot where I shall end it.” It was a kind of private joke, one that FitzRoy probably didn’t get. Darwin’s head was full of barnacles at the time—he was trying to map and understand the entire group and would continue for another eight years, so when he wrote “I am fixed on the spot where I shall end it,” he was thinking of himself as a barnacle that had glued itself to a rock now that its free-swimming days were over.

Life here went on like clockwork because Darwin made it so. Every hour of his day was scheduled to roughly the same pattern for 40 years: a walk before breakfast, then work from 8 a.m. to midday, with a pause in mid-morning to listen to Emma read novels or family letters aloud. He went for a walk with his dog before lunch, the family’s main meal, at 1 o’clock. Then he read the newspaper, wrote letters or read until 3 o’clock, then rested, working again from 4:30 to 5:30. A simple dinner was served at 7:30, after which he played backgammon with Emma or billiards with his children or listened to Emma play the piano.

The routines were not just Darwin’s; the house ran like clockwork, too. Emma made sure of that. Everyone worked to time and in time. Yet it was also a liberal house, always slightly untidy, muddied from the passing of children and their dogs and cluttered with the saucers and jars of perpetual natural history experiments.

Darwin needed this house to be a refuge. Though he was sometimes gregarious and social, he suffered from a debilitating illness that made him uncomfortable among strangers. The symptoms, which included nausea, vomiting and flatulence, embarrassed him. Scholars still disagree on the cause of Darwin’s condition: Some say it was a tropical disease contracted on the Beagle voyage; others argue that it was anxiety-related or an allergic reaction to food. Despite his illness, Darwin would need to go up to London—to attend events, dinners, meetings and to buy equipment such as dissecting scissors or a new microscope, or to order wallpaper with Emma or to see the monkeys at the zoo with the children—but living only 15 miles away he could be back quickly. And at home, he could retreat into his study, where he had everything he needed behind a little screen—pills, bowls, towels, hot water—and where he could give himself up to his illness.

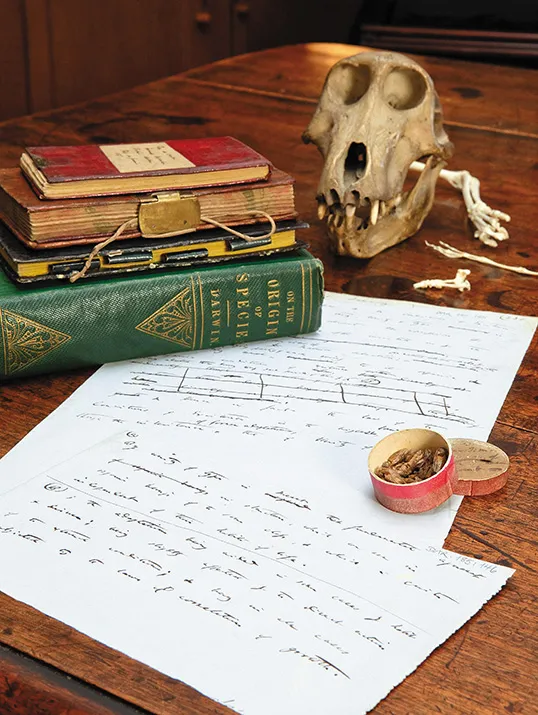

Darwin’s study is darker than the other rooms, a cave, a sanctuary, a room for thinking, reading, writing and dissection. It has been reconstructed just as it was when Darwin used it: a delightful jumble of original furniture rescued by the family from attics and storerooms, surfaces cluttered with bottles, books, microscopes, even the spool young George made for his father’s string. The room brilliantly recreates the “general air of simpleness, makeshift, & general oddness” that his son Francis fondly remembered. Here is the mirror that Darwin had placed so that he could spot unwanted visitors approaching up the drive and slip away if he needed to. Here is the low stool with casters that he used to spin himself from one desk where he dissected in front of the window to another where he took notes or wrote up labels—the stool the children were allowed to use for their games, punting themselves around the living room with long poles. Here is the rotating table containing his dissecting equipment, forceps, ink, small bottles, rolls of string, sealing wax and small squares of sanding paper. It made me want to rummage in the drawers, unstopper the bottles to smell the preserving fluids, look down the microscope, sit in that sagging chair.

The children were allowed into the study occasionally, as long as they did not disturb their father for too long. They came looking for bits of string or glue or sometimes to smuggle their father the snuff he loved but which Emma rationed. Through the 1840s and ’50s it was a room given over almost entirely to barnacles—dissected, preserved, fossilized—piled high with white pillboxes in which Darwin kept the hundreds of labeled specimens sent to him from collectors all over the world; some are still there. When George visited a friend during this time and was told his friend’s father did not have a study, he asked incredulously: “But where does your father do his barnacles?”

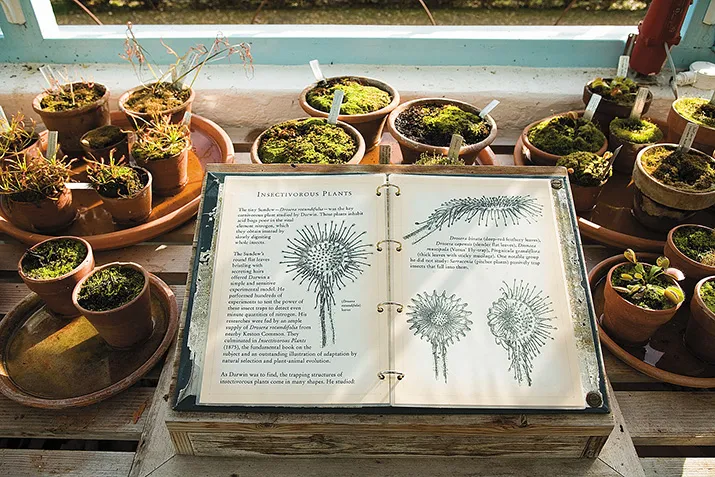

The father in Down House did barnacles and he did bees and he did carnivorous plants and he did worms. And if the father did them, so did the children. These children were willing and happy assistants to their attentive father, fascinated by his explanations of the natural world. As soon as they were old enough, they were recruited to oversee certain experiments—to observe seeds growing on saucers arranged on windowsills, or to play music to worms, or to follow and map the flight path of the honeybees across the Down House gardens. They were also the subject of his studies; he watched them play and laugh and cry, keeping notebooks full of observations of the young human animals they were.

One of the most striking things about visiting this house in autumn is the exquisite Virginia creeper that has stretched its way up and over the painted white brickwork. The flame-red leaves had almost all fallen, leaving just the delicate black branches of the stems, as intricate as sea fans. It struck me too as I walked around the house how many family trees English Heritage has assembled on the interior walls to illustrate the kinship connections between the Darwins and the Wedgwoods (Emma Wedgwood, from the wealthy manufacturing family whose potteries produced fine porcelain, and Charles Darwin were first cousins). Those branching patterns seemed to be replicated everywhere inside and outside the house, like branches but also like nets. “We may all be netted together,” Darwin wrote in an early notebook, referring to his gathering conviction that all races came from a common ancestor.

Walking around this house you do get a strong sense of nettedness, of the intricate kinships between its diverse human and animal members. In the last years of his life, Darwin became obsessed with earthworms. He brought them into the house in glass jars full of soil to observe their reactions to things, getting the children to serenade them in the billiards room—bassoon, piano and whistle—flashing lights at them to determine how sensitive they were, feeding them odd kinds of food, including herbs and raw meat. They were, he knew, the great workers, the overlooked, the toilers and tillers of the soil. All life on the planet depended upon the work they did. “It may be doubted,” he wrote, no doubt thinking of the continual turning of the planet, birth to death, death to birth, “whether there are many other animals which have played so important a part in the history of the world as have these lowly organised creatures.”

The whole house is much the same as it was when Darwin lived there, except, of course, that when Darwin lived there it was always changing. That is the trouble with such houses, preserved for the nation: They fix a place in a moment in time, and Darwin and his family were never still, never fixed. They and the house they lived in evolved.

It is tempting to think about Down House and its occupants moving through time like fast-frame photography, like the lyrical “Time Passes” section of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, in which she describes an empty holiday house on the Outer Hebrides over a period of ten years. As I stood on the stairs for a moment, visitors passing, overhearing scraps of conversation, looking down the long corridor to the tall window framing trees ahead, I was convinced I felt time move. It had something to do with the sound of the piano playing in one of the exhibition rooms, I think, which reminded me that Darwin would have heard family sounds as he worked, children thumping up and down those stairs, nursemaids calling, builders sawing and hammering somewhere, working on some repair or a new extension, Emma playing the piano in the drawing room, dogs barking, the muffled voices of gardeners on the lawn outside.

But Down House is not a ghostly place; it’s not a tomb or a stone memorial. It is still as open to the garden and the sun as it ever was. It continues to move through time. There are gourds and pumpkins in the garden, scores of pots of drosera and orchids in the greenhouses; the gardeners tend the trees and the orchards, and in the kitchen garden children weave in and out of the pathways playing hide-and-seek. Bees still make honey here; birds catch their worms; and under the ground the worms grind away, turning over the soil.

Darwin built himself the Sandwalk, a sand-surfaced path on which he could walk and think, soon after they moved into the house. He walked it several times a day, almost every day of the year. It began at the gate at the end of the kitchen garden. On one side it followed the ridge of a hill so that the views looked down over open meadows, and on the other, as it circled back toward the house, it took him into the cool darkness of the wood he had planted. Those looped repetitions through the same ground were a kind of meditation. He came to know the interdependent life of this little wood as it changed through the seasons; he came to understand the sense of life and death all intricately netted together. He came to know its light and its darkness.

Down House knew loss as it knew life. Charles and Emma lost their first baby only days after moving in here; they lost their daughter Annie in her tenth year. Annie’s distraught father nursed her at her bedside in a water-cure establishment many miles away from Emma, who was too heavily pregnant to reach him or their dying daughter. After Annie’s death, he remembered his daughter running ahead of him on the Sandwalk, turning to dance or smile. Her absence, the traumatic memory of her painful death from an undiagnosed illness, was a continual reminder of the fragility of life that tempered the daily joy afforded him by his growing children. The Sandwalk and Down House itself, in all its netted, interdependent beauty and wonder, were places of emotional chiaroscuro.

When Darwin finally finished Origin of Species, a book written through sleepless nights and at white-hot speed, he allowed himself to compose a little prose poetry on its final page, now one of the most quoted passages of all his writing. “It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank,” he wrote, “clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms...have all been produced by laws acting around us....Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals directly follows....From so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” This passage is, I think, also a poem about his home, a poem about the evolving world he and Emma had created together at Down House.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.