The Lure of Capri

What is it about this tiny, sun-drenched island off the coast of Naples that has made it so irresistible for so long?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Capri-Faraglioni-pinnacles-631.jpg)

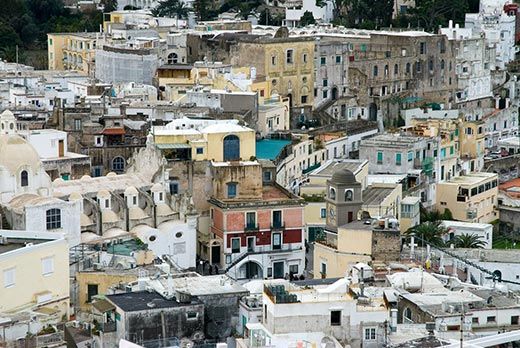

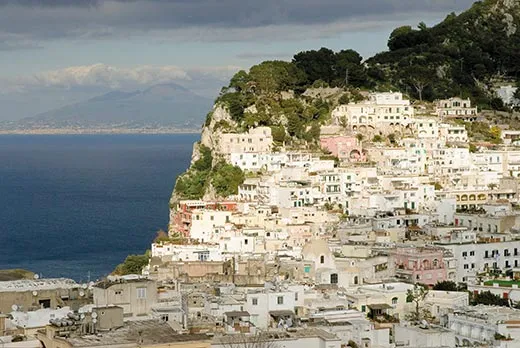

In most of the world, scheduling a concert for 6 a.m. would be eccentric, to say the least. Add that the venue is a cliff-side grotto reachable only by a half-hour hike, and it sounds almost perverse. Not so on Capri, the idyllic island in Italy’s Gulf of Naples whose natural beauty has drawn gatherings since Roman times. As tuxedoed waiters closed down the last cafés at 5:30 a.m., I accompanied an elderly Italian couple dressed as if for the opera through dark, empty plazas in the island’s town center, also called Capri. We came to a cobbled footpath that led to the grotto, turned on our flashlights and made our way past moonlit lemon groves and gated villas. It was a velvety summer night, and my new companions, Franco and Mariella Pisa, told me they divided their time between Naples and Capri, much as their parents and grandparents had done before them. “Capri has changed on the surface,” Mariella said, “but its essence remains the same.”

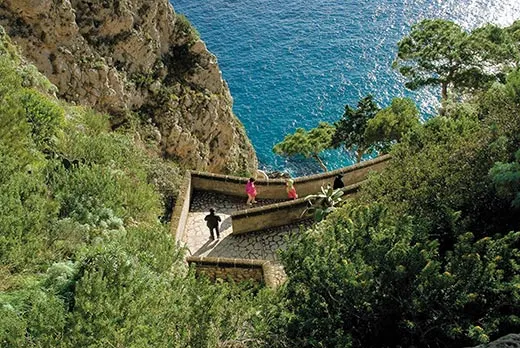

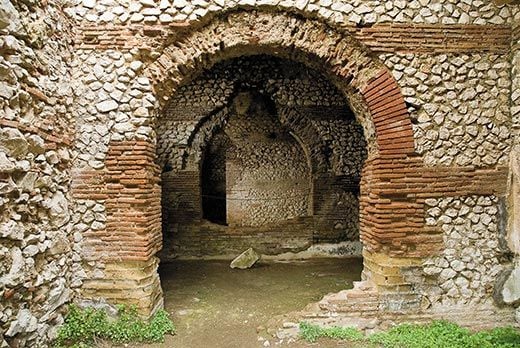

Finally, after negotiating a series of steep stone steps down the side of a cliff, we arrived at the candlelit Matermània Grotto, a cavern half open to the night sky, where traces of an ancient Roman shrine are still visible. In antiquity, this had been a nymphaeum, or shrine to water nymphs, decorated with marble statues and glass mosaics, artificial pools and seashells. Legend holds that the grotto was also a place for the worship of Cybele, the pagan goddess of the earth, known as Magna Mater, or Great Mother, who gave it its name. “The Romans loved natural energy,” Filippo Barattolo, director of Capri’s Ignazio Cerio Museum and Library, would tell me later. “They regarded the island’s grottoes as sacred places where they could commune with the divine.” Now, as candlelight danced on cavern walls, other immaculately dressed Italians—bronzed gents in white silk trousers, women in sequined dresses, some carrying tiny canines—took their seats on rocks around its entrance. The group swelled to about 100.

The starlit sky had just begun to lighten when the sound of bells tinkled through the grotto and a lone cellist launched into a discordant experimental piece. In the predawn light, I could see that the cave opened out upon the jagged eastern coastline, where sheer cliffs and spires plunge into the Mediterranean—“galloping rocks” that provide “exclusive balconies for elegant suicides,” the Italian futurist poet F. T. Marinetti wrote in the 1920s. No wonder the ancients regarded Capri as the domain of the sirens, those Homeric creatures who lured sailors to their demise with seductive songs. As the sun began to rise, the music shifted to a lyrical nocturne, and hundreds of birds began to chatter in the surrounding trees. The guests were then offered a suitably pagan repast of fresh green grapes, bread and milk.

In the early 1900s, expatriate bohemians gathered in the Matermània Grotto for faux-pagan celebrations of a more bacchanalian nature. One in particular has gone down in legend. In 1910, Baron Jacques d’Adelswärd-Fersen, an opium-addicted French poet (whose neo-Classical villa attracts tourists today), staged a human sacrifice to the ancient Roman sun god Mithras. While a crowd of friends in Roman tunics held torches, burned incense and sang hymns, Fersen, dressed as Caesar, pretended to plunge a dagger into the chest of his naked lover, Nino Cesarini, cutting him slightly. A young shepherdess who witnessed the pageant told a local priest about it. In the ensuing scandal, Fersen was forced to leave the island—albeit briefly—one of the few cases on record of Capresi being outraged by anything.

For over 2,000 years, this speck in the Gulf of Naples, only four miles long and two miles wide, has been known for its dazzling beauty and extreme tolerance. Writers, artists and musicians have long been drawn to its shores. “Capri has always existed as un mondo a parte, a world apart,” said Ausilia Veneruso, the organizer of the Matermània Grotto event and, with her husband, Riccardo Esposito, owner of three bookshops and a publishing house that specializes in writings about Capri. “It is the hermaphrodite island, a collision of mountains and sea, where opposites thrive and every political ideology and sexual preference finds a place,” she told me. “By the 19th century, our little island was for artists like the center of the world: Europe had two arts capitals, Paris and Capri.”

Capri’s cosmopolitan past remains part of its allure. “For centuries, Capri was shaped by foreign travelers,” said Sara Oliviera, vice president of the Friends of the Certosa (monastery) of Capri. “The island was a crossroads of international culture. Now we want to revive those connections.”

The island’s first tourists were the Romans, who were attracted by its ravishing scenery and its aura of refinement as a former Greek colony. During the second century B.C., the entire Bay of Naples blossomed into a seaside resort. Roman aristocrats, including the emperor Augustus himself, would travel by horseback or wagon to Sorrento, then sail the three miles to Capri to escape the summer heat and to indulge in otium, or educated leisure—working out, swimming, dining and discussing philosophy. In this Hamptons of antiquity, Roman girls cavorted on the pebbly beach in prototype bikinis.

But the figure who most thoroughly shaped Capri’s fate was Augustus’ successor, the emperor Tiberius. In A.D. 27, at the age of 69, Tiberius moved to Capri to govern the enormous Roman empire from his dozen villas here. For more than a decade, according to his biographer, Suetonius, Tiberius wallowed in hedonism—decorating his mountaintop Villa Jovis, or Villa of Jupiter, with pornographic paintings and statues, staging orgies with young boys and girls and torturing his enemies. (The ruins of the villa still exist; its tunnels, arches and broken cisterns crown the island’s eastern cliffs, from which the emperor was said to have tossed those who displeased him to their deaths.) In recent years, historians have discounted Suetonius’ depiction, which was written some eight decades after Tiberius’ death. Some say the emperor was actually a recluse who preferred stargazing to pederasty. “The trouble with all Suetonius’ gossip about Tiberius is that it’s just that: gossip,” says Paul Cartledge, a professor of Greek culture at Cambridge University. “He could have been a shy, retiring student of astrology. But he was possibly also a sexual deviant. We’ll never know for sure.”

Yet the image of Tiberius’ indulgences became a fixture of Capri’s reputation, repeated as gospel and perpetuated in Robert Graves’ historical novel I, Claudius and in the lurid 1979 film Caligula, starring a haggard-looking Peter O’Toole as the imperious reprobate. But if Tiberius lent the island a dreadful notoriety, he also guaranteed its popularity. Its divine beauty would forever be inseparable from its reputation as a sensual playground, where the pursuit of pleasure could be indulged far from prying eyes.

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in A.D. 476, Capri entered a lonely period. Throughout the Middle Ages, Arabs and corsairs routinely raided the island. Capri began to regain its popularity in the 1750s, when excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum, the Roman towns buried by an eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79, made Naples a key stop on the grand tour. Travelers, including the Marquis de Sade, in 1776, added Capri to their itineraries. (He set a part of his licentious novel Juliette at the Villa Jovis.)

The “discovery” of a natural wonder, the Grotta Azzurra, or Blue Grotto, only boosted the island’s popularity. In 1826, August Kopisch, a young German writer touring Italy, heard rumors of a sea cave feared by local fishermen. He persuaded some boatmen to take him there. After swimming through a small opening in the rocks at the base of a towering cliff, Kopisch found himself in a large cavern where the water glowed, he would write, “like the light of a blue flame.” It made him feel as if he were floating in an “unfathomable blue sky.” Further inspection revealed the source of the light: an underwater cavity that allows sunlight to filter in. Kopisch also found an ancient landing in the back of the grotto; islanders told him it had once been the entrance to a secret tunnel that led to one of Tiberius’ palaces, the Villa Damecuta, directly above. The grotto itself, they said, had been a nymphaeum.

Kopisch described his explorations in The Discovery of the Blue Grotto on the Isle of Capri, which tapped into the Romantic era’s interest in the spiritual and healing powers of nature. Soon travelers were arriving from Germany, Russia, Sweden and Britain to revel in natural beauty and escape conventional society. At the time, Capri had fewer than 2,000 inhabitants, whose traditional rural life, punctuated by religious feasts and the grape harvest, added to the island’s allure. Affluent foreigners could rent dirt-cheap rooms, dine under vine-covered pergolas and discuss art over light Caprese wine. In the village cafés, one might spot Friedrich Nietzsche, André Gide, Joseph Conrad, Henry James or Ivan Turgenev, who raved about Capri in an 1871 letter as “a virtual temple of the goddess Nature, the incarnation of beauty.”

The German artist Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach wandered around the island in the early 1900s wearing a long white tunic and gave tormented sermons to passersby in the town piazza. Former Confederate colonel John Clay H. MacKowen, who went into self-imposed exile after the Civil War, filled an enormous red-walled villa in Anacapri (Upper Capri) with antiquities. (The villa, known as the Casa Rossa, is open to the public today.) In 1908, the exiled Russian author Maxim Gorky started the School of Revolutionary Technique at his villa. One guest was Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, a.k.a. Nikolai Lenin, on the run from Czarist police after the failed revolution of 1905 in Russia.

Among this illustrious parade was a Swedish doctor, Axel Munthe, who, like so many others, came to Capri for a brief visit, in 1875, and fell in love with it. A decade later he moved to the village of Anacapri and built the Villa San Michele on the crest of a hill with stunning views of the Mediterranean. He filled the villa’s lush, secluded gardens with Roman statues, a stone sphinx and a carved Medusa head, most of which had to be carried up the 800 or so steps from the main harbor by mule. The Story of San Michele (1929) was translated into 45 languages and carried the island’s charms to a new audience. Today the Villa San Michele is a Swedish cultural center and bird sanctuary, and remains, in Henry James’ words, “a creation of the most fantastic beauty, poetry and inutility that I have ever seen clustered together.”

Writer Graham Greene and the exiled Chilean poet Pablo Neruda arrived later—in the 1940s and ‘50s, respectively. Although neither included Capri in his work, both of their sojourns were immortalized posthumously—Neruda’s in the fictionalized 1994 film Il Postino, and Greene’s in the 2000 biography Greene on Capri.

Not everyone saw the island as an Eden. In fact, a recurrent note of melancholy runs through many of the writings about Capri. Even Munthe, who had treated cholera patients during an epidemic in Naples, seems haunted by death and decay in his memoir. The modern Caprese author Raffaele La Capria insisted in his 1991 book Capri and No Longer Capri that morbid thoughts are inseparable from the island’s timeless beauty and rich history, which force “you [to] face with a shudder the ineluctable fact that you too will die.”

Somerset Maugham, who was a regular visitor, captured the dark side in his classic short story “The Lotus Eaters,” about a British bank manager who throws over his life in London to live in Capri and swears to commit suicide when his money runs out. But years of indolent island living sap his willpower, and he spends his last days in poverty and degradation. The character was based on Maugham’s friend and lover, John Ellingham Brooks, who came to Capri as part of an exodus of homosexuals from England in the wake of Oscar Wilde’s conviction, in 1895, for “acts of gross indecency.” Brooks, however, escaped the fate of Maugham’s character by marrying a Philadelphia heiress who, though she quickly divorced him, left Brooks an annuity that allowed him to spend out his days on Capri, playing the piano and walking his fox terrier.

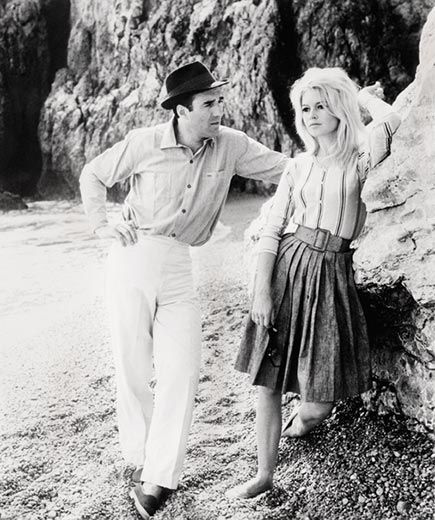

After World War II, the island provided the setting for a string of movies, including the romantic comedy It Started in Naples (1960), starring Clark Gable and Sophia Loren, and the mildly risqué If This Be Sin (1949) and September Affair (1950). In the most enduring of the lot, Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963), a young bikini-clad Brigitte Bardot plunges into the crystal blue Mediterranean from the rocks beneath the breathtaking Villa Malaparte, built between 1938 and 1942 by proto-Fascist poet Curzio Malaparte.

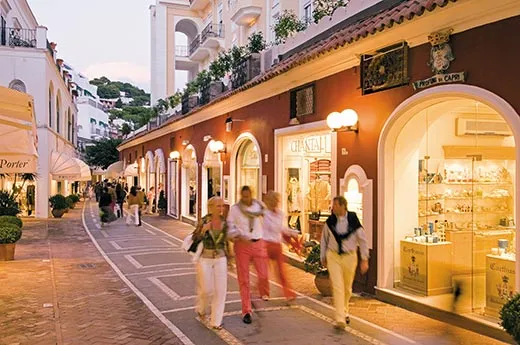

Today the island is more popular than ever, as shown by its two million visitors annually. Residents are worried. “Once, visitors would rent a villa and stay for a month,” says bookshop owner Ausilia Veneruso. “Now they come for only two or three days, or even worse, come as i giornalieri, day-trippers. And Capri is a very delicate place.” The influx has led to overfishing and overdevelopment. “The sea is lost,” Raffaele La Capria writes in Capri and No Longer Capri, “more lost than Pompeii and Herculaneum,” while the island itself suffers “a kind of process of dry putrefaction.”

Still, peace and solitude can be found, even in summer. Most tourists cluster around the marinas and piazzas, leaving the miles of hiking trails along the island’s rugged west coast virtually empty, including a three-hour Route of the Forts, which links several medieval fortresses. And after the day-trippers leave in early evening, even Capri town appears much the same as it did when Gable watched Loren sing “You Wanna Be Americano” in a nightclub.

Out of fear of being disappointed, I delayed my visit to the Blue Grotto, which has become a symbol of Capri’s overcommercialization. Hundreds of boatmen ferry tourists in and out of the sea cave in a perfunctory parade. Then, on the day I finally chose to visit it, the grotto was closed because of a mysterious sewage spill; it was rumored that the Neapolitan mafia had dumped waste there to damage Capri’s tourist trade, for reasons unknown.

But after a few cleansing tides had allowed the grotto to be reopened, I took a bus to Tiberius’ Villa Damecuta and descended the cliff steps to sea level. At 7 p.m., after the commercial boats stop working, a number of intrepid tourists swim into the grotto, ignoring the posted signs warning against it. I joined them and plunged into the waves. After swimming the few strokes to the opening, I pulled myself along a chain embedded in the wall of the cave entrance, the waves threatening to dash me against the rocks every few seconds. Soon I was inside, and my eyes adjusted to the darkness. Deep beneath my feet, the water glowed that famous fluorescent blue, which Raffaele La Capria writes is “more blue than any other, blue below and blue above and blue along each curve of its vault.” I was not disappointed. The magic endures.

Tony Perrottet’s new book, The Sinner’s Grand Tour, is due out next month. Francesco Lastrucci photographed the Sicilian mafia story for the October 2010 issue.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)