The Mustang Mystique

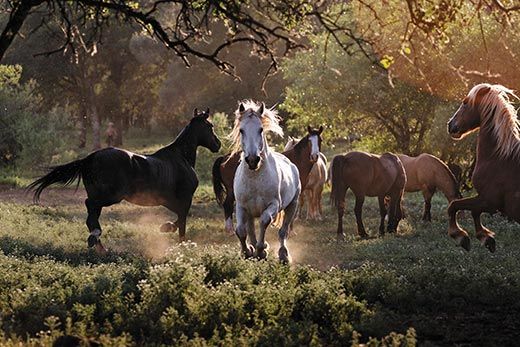

Descended from animals brought by Spanish conquistadors centuries ago, wild horses roam the West. But are they running out of room?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/rescued-horses-studs-challenging-harem-stallions-in-fog-631.jpg)

To create her haunting, intimate photographs of wild mustangs, Melissa Farlow staked out water holes across the West. In Nevada’s Jackson Mountains, she slathered on sunscreen; in Oregon’s Ochoco National Forest, she wore snowshoes. Visiting a South Dakota mustang preserve on a Sioux Indian reservation, she was lost in fog for what seemed like hours; at last she heard a soft nicker from a horse just 20 feet away, hidden in the mist.

When Farlow was photographing a herd in Oregon’s remote Steens Mountain area, a pinto stallion charged out of the sagebrush at her, hooves churning. “All of a sudden I just sat down,” Farlow said.

It worked. Seemingly assured of his own supremacy, the stallion quit snorting and stomping, and before long the photographer found herself being sniffed by mares and foals.

Farlow spent part of her childhood astride a one-eyed cow pony in southern Indiana and has photographed the lustrous Thoroughbreds of Kentucky’s Bluegrass Country. But mustangs, she realized from spending months among them, are not ordinary horses. They are living emblems of the Old West, fleet exiles from a fenced world.

Mustangs are the feral descendants of 16th-century steeds the conquistadors brought to North America. The name comes from the Spanish mestengo, meaning stray. By the mid-1600s, Plains Indians were capturing and taming horses—which the Lakota called sunka wakan, or sacred dog—and the animals revolutionized their cultures. The Crow and the Sioux tribes mounted spectacular war parties and hunted on horseback. White settlers also pressed mustangs into service, as did U.S. troops—including George Armstrong Custer’s Seventh Cavalry—that battled the Great Plains peoples.

A ranger in Texas’ Wild Horse Desert in the mid-1800s described a herd that took an hour to pass: “as far as the eye could extend on a dead level prairie, nothing was visible except a dense mass of horses.” Escaped cavalry chargers and other runaways mixed with the original Spanish herds. Perhaps as many as two million mustangs were rambling around the western half of the country by the end of the 19th century, according to Deanne Stillman, who consulted roundup, slaughterhouse and other records for her book Mustang: The Saga of the Wild Horse in the American West.

By the early 20th century, mustangs were being sold in Europe as horse meat, turned into glue, pet food and pony fur coats in the United States, herded and harassed by airplanes and shot for sport. In 1950, Velma Johnston, a bank secretary on her way to work in Reno, Nevada, followed a livestock truck leaking blood, then watched in horror as wounded mustangs were unloaded at a slaughterhouse. Johnston, later called Wild Horse Annie, spent the rest of her life fighting for laws that culminated in the federal Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, which protected mustangs on public lands. There were then about 17,000 wild mustangs left.

Today, some 37,000 of them roam more than 30 million acres of public land in the West, with large populations in Nevada, California, Utah, Wyoming and Oregon. In places where the animals are most concentrated—half of the horses live in Nevada—new problems are surfacing. Their overgrazing can lead to erosion and water pollution and make way for pesky invasive species like cheatgrass. Such ecological damage causes food shortages for the horses as well as the sage grouse, bighorn sheep, elk and domestic cattle that share their pastures.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which is responsible for most of the wild mustangs, has plans to reduce the number under its jurisdiction by roughly 12,000 in 2010. This winter, the agency led a two-month-long helicopter “gather” in northwestern Nevada’s Calico Mountains to relocate 2,500 horses, one of the largest roundups in recent years.

Captured mustangs are sold to private owners for an average of $125 apiece. But a horse is expensive to maintain and can live 25 to 30 years; adoptions of wild horses and burros were down from 5,700 in 2005 to fewer than 3,500 in recessionary 2009. Across the West, BLM workers are injecting some mustang mares with contraceptive drugs to limit herd size, and they may geld some stallions. In 2008, the agency announced its intention to euthanize some unadoptable horses; the plan was scrapped after a public outcry. More than 34,000 unwanted mustangs live out their days in government corrals and holding pastures; last year, holding costs alone were $29 million.

Mustang advocates find the idea of fenced-in wild horses distasteful in the extreme. The BLM “treat(s) the wild horses like livestock,” says Karen Sussman, president of the International Society for the Protection of Mustangs and Burros, an organization first led by Wild Horse Annie. The horses, she says, should be treated “like wildlife.”

“Mother Nature can be very cruel,” says BLM spokesman Tom Gorey, and in areas crowded with horses the animals can starve to death. “The idea of just allowing nature to take its course—people don’t have the stomach for that,” he says. “We don’t have the stomach for it either.”

Farlow photographed several roundups, including one in the Jackson Mountains. She set up her remote-controlled cameras, then watched from a hillside as the horses pounded past, two helicopters buzzing above. A tame horse, known in the trade as a Judas horse, was released among the mustangs; they followed him into the corral and the gates were closed. “It’s a bit heartbreaking,” Farlow says. “Some of these horses are so beautiful that you want to say, ‘Turn around and run!’”

Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian’s staff writer, has written about lions, narwhals and monkeys called geladas. Melissa Farlow is a freelance photographer based in Sewickley, Pennsylvania.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.