The Mystique of Route 66

Foreign tourists and local preservationists are bringing stretches of the storied roadway back to life

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Route-66-Anna-Matuschek-631.jpg)

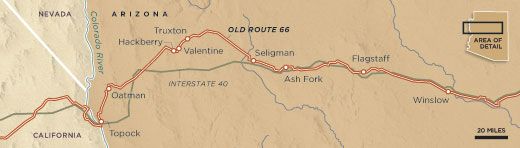

Since I discovered U.S. Route 66 as a teenage hitchhiker, I’ve traveled it by Greyhound bus and tractor-trailer, by RV and Corvette and, once, by bicycle. Recently, when I wanted to return for another look, I headed straight for my favorite section, in Arizona, stretching from Winslow west to Topock on the California border. The last 160 miles of that route constitute one of the longest surviving stretches of the original 2,400-mile highway.

I’m happy to report that Route 66’s obituary—written repeatedly since 1984, when the opening of I-40 enabled motorists to make the trip from Chicago to Los Angeles on five connecting interstates—was premature. What John Steinbeck called the Mother Road had been reborn, not quite with the character it once had, but with enough vitality to ensure its survival.

When I reached Seligman, I called Angel Delgadillo at his home. He set his tenor sax aside to pedal his bike the few blocks to his barbershop and settled into his hair-cutting chair, a cup of coffee in hand. “You know,” he said, “even the Greyhound abandoned us” after I-40 opened. “So I sit here today and say to myself, ‘It’s pretty unreal how we’ve brought 66 back to life.’ ” Seligman has 500 residents—and 13 souvenir shops selling Route 66 memorabilia.

“We’ve got a tour bus pulling up,” his daughter Myrna shouted from the adjacent gift store. Delgadillo, who is 84, bounded out of his chair, wearing a smile as wide as a crescent moon, and rushed to greet a group of German tourists, shaking hands and slapping backs. “Good morning, good morning! Welcome home.” Home? They gave him a quizzical look, not understanding that to Delgadillo, Route 66 is a quintessential home to all the world’s wanderers, even though he himself had never strayed far from it.

The tourists loaded up on postcards, Route 66 bumper stickers, road signs shaped like shields and black-and-white photographs of dusty Ford Model Ts chugging through Seligman in the 1930s, canvas water bags slung on their hoods to keep radiators from overheating. I asked one of the visitors, a 40-ish man named Helmut Wiegand, why in the world a foreigner would choose this road for a vacation over Las Vegas, New York City or Disney World. “We all know 66 from the old TV series about two lost young men traveling it in a Corvette,” he said. “For us, 66 is a connection with America. It’s your most famous street, symbolic of your freedom, your restlessness, your quest for new opportunity.”

As the travelers returned to their bus, Delgadillo shook hands with each of them. He was born in Seligman, the son of a railroad man who owned a pool hall and barbershop but had a hard time supporting his family of seven. “In ’39 Dad built a trailer for our Model T, loaded it up and shuttered the windows of our house,” he said. “We were ready to join the Okies and go to California.” But his three brothers had formed an orchestra, with 12-year-old Angel on the drums, and the boys got a job performing in a local club. For the next four decades, they played at high-school dances, American Legion halls and VFW lodges, and community events along Route 66. “The highway saved us,” said Delgadillo, who is now known locally as “the Angel of Route 66” for his preservation efforts.

The road west from Seligman cuts through the Hualapai Indian Reservation and desert plateaus covered with juniper and mesquite. Red-rock cliffs thrust skyward on the horizon. In the 1850s, U.S. Navy Lt. Edward Beale traveled this route, along centuries-old Indian trails, with 44 men and 25 camels imported from Tunisia. Beale and his men created the first federally funded wagon road across Arizona, from Fort Defiance to the mouth of the Mojave River in California. The first telegraph lines to penetrate the Southwest territories soon followed, as did settlers in covered wagons and then railroads. Finally, in 1926, black Model Ts came chugging along an intermittently paved road designated as Route 66. It wasn’t the first road across the West; the Lincoln Highway, known as the Father Road, was dedicated in 1913, running 3,389 miles from New York City’s Times Square to San Francisco’s Lincoln Park. But 66 became synonymous with wanderlust and discovery.

For Cyrus Avery, the new road was a dream come true. A visionary Tulsa businessman and civic leader, Avery had persuaded federal officials designing the nation’s first comprehensive highway system to move the proposed Chicago-Los Angeles route south of the Rocky Mountains so it traveled through his hometown. Oklahoma ended up with 432 miles of Route 66, more than any state except New Mexico; 24 miles of the road snaked along Tulsa County’s residential and commercial streets. The thoroughfare spurred the development of a city that had, Avery would later recall, “no electric lights and pigs running on the streets” in the early 1900s. A few years ago the city of Tulsa purchased two acres of blighted land near the Cyrus Avery Memorial Bridge spanning the Arkansas River and built a plaza and skywalk. But the centerpiece of the $10 million-plus project will be a Route 66 museum and interpretive center, still in the planning stages.

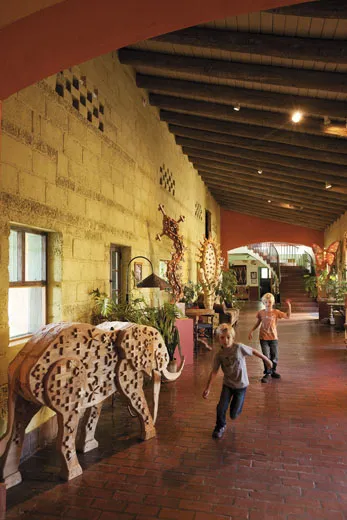

The last time I traveled the road, crossing the open range and Painted Desert of northern Arizona in 1995, Winslow was a dying town. Route 66, which had become 2nd and 3rd streets, was a shambles of closed shops and nasty-looking bars. The magnificent La Posada, last of the famous Fred Harvey hotels built between Chicago and Los Angeles for rail and Route 66 travelers, had been closed in 1957 and converted into offices for the Santa Fe Railway. The Posada’s splendid murals, depicting desert flowers and Southwestern landscapes, had been painted over. The soaring timbered ceiling had disappeared under tiles fitted with fluorescent lights. The lobby was turned into a dispatch center for trains and the ballroom partitioned into cubicle offices. The original museum-quality furnishings, designed or selected by the building’s creator, Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, regarded by many to be the Southwest’s greatest architect, had been auctioned off or given away. In 1992, even the Santa Fe Railway gave up on the place, reportedly offering it to the city for $1. Winslow said no thanks.

Then in 1994, Daniel Lutzick, Tina Mion and her husband, Allan Affeldt—friends who had attended the University of California at Irvine together in the 1980s—showed up in Winslow. Residents viewed them with a mix of suspicion and hope. The three talked about taking over La Posada and restoring it. What the town didn’t yet realize was that Lutzick was a sculptor, Mion an accomplished portrait painter and Affeldt a successful preservationist.

After three years of negotiation, the Santa Fe Railway sold them La Posada for the price of the land, $158,000 for 20 acres. The hotel was thrown in free. The trio moved in on April Fool’s Day 1997, shooing away some hobos, and set to work. Seven months later, La Posada reopened with five meticulously restored guest rooms. The new owners operated in the red for five years; sometimes they met payroll with Affeldt’s credit cards. They scrambled for grants and put everything they made back into the project.

Now the 53-room hotel is booked to capacity virtually every night. Its Turquoise Room is regarded as one of the Southwest’s top restaurants. The grounds are landscaped with towering cottonwoods and hollyhocks. With a paid staff of 50, La Posada is the largest locally owned employer. Winslow has awakened from a 50-year slumber with a revived downtown, new shops, sidewalks and streets.

“Architecture is what brought us here,” Affeldt told me. “But what Route 66 gave us was a built-in audience—the people going up and down the road for whatever reason: architecture, history, nostalgia. Having 66 on our doorstep made all the difference.”

As is often the case when it comes to a piece of history, people didn’t realize the value of what they had until it was gone, or nearly so. Today they seem to be remembering with a vengeance. The quarterly magazine Route 66 has 70,000 subscribers in 15 countries. Michael Wallis’ book, Route 66: The Mother Road, published in 1990 and updated in 2001, has sold about a million copies. Tulsa has held a marathon on its section of Route 66 for the past six years, attracting 12,000 runners and walkers last November. A Montana-based nonprofit, Adventure Cycling, which produces detailed maps for long-distance cyclists, has begun a Route 66 project. “People have contacted us for years, from all over the world, asking, ‘Why don’t you have a [map for] 66 ?’ Now, we’re going to,” says Ginny Sullivan, special projects manager for the group. And the National Park Service is providing grants under its Route 66 Preservation Program to rehabilitate significant elements along the original road—funky service stations and motels that once advertised “Cheap Clean Sleep, Thermostat Heating” and neon signs that beckoned travelers toward 99-cent chicken-fried steak dinners and $2 rooms.

A fiery sunset blazed across the desert sky, and wind-tossed tumbleweed danced down the long stretch of 66 that leads to Truxton, Arizona (pop. 134). Ahead, a tree-high sign—rewired, repainted and artfully restored with a federal grant—flashed a red-neon welcome for the seven-room, 1950s Frontier Motel and café.

I first met its owner, Mildred Barker, and her husband, Ray, 33 years ago. Some years later I sat at their counter, eating homemade apple pie a la mode, with Ray’s 88-year-old stepfather, who recalled busting broncos in the Cherokee Nation before Oklahoma even became a state in 1907. That day Mildred had stepped out of the kitchen, a blue-plate special in each hand, recognized me and asked, “You still in that RV?” No, I said, I’d found something slower and cheaper. Outside, my bicycle, with four bulging saddle bags hanging over its wheels, rested against the battered Frontier sign. “My word!” she said. “I’m buying your meal today.”

When last I found Mildred, now 86 and full of memories, she complained that the pie under the new management that had leased the café wasn’t up to the standards she had set. She had decided to stay on in Truxton, she told me, because her husband, who died in 1990, had worked so hard to save the road. “You know,” she said, “I lived my entire life on 66—Oklahoma, New Mexico, now here. This wasn’t just a road. It was my history, my life.”

The next morning, I left early, pushing westward, dipping into Crozier Canyon, with its craggy, boulder-strewn hillsides, passing the long-closed Indian School that stands near the abandoned one-room “non-Indian” school in Valentine. The way was littered with relics: remains of a motel named Chief’s, a derelict Union 76 gas station, a Ford Model A rusting in sagebrush, buried to its hubcaps in sand.

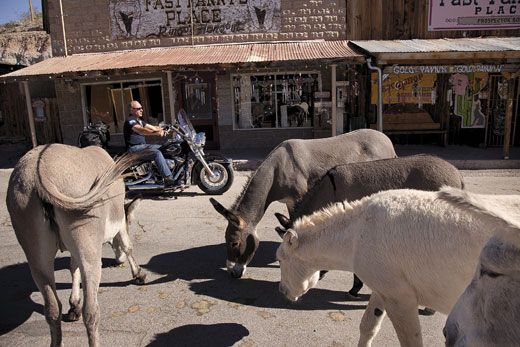

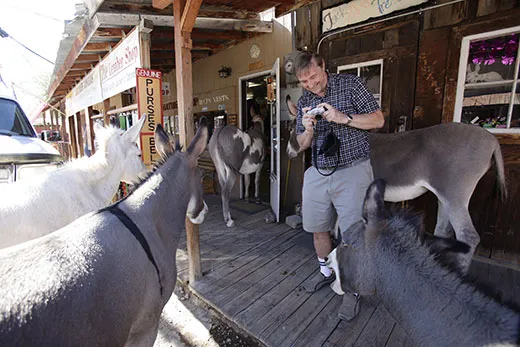

In one old railroad town, I pulled off the empty highway for a cold Route 66 root beer in the Hackberry General Store. The owner’s 1957 red Corvette convertible was parked out front. As I headed for the soda fountain, making my way past shelves of Route 66 memorabilia, I half expected to see Martin Milner and George Maharis, the actors who wandered the country in a ’Vette as Tod Stiles and Buz Murdock in the CBS-TV series “Route 66” for four years starting in 1960, the year after my maiden voyage down the road.

John Pritchard, who owns the store with his wife, Kerry, began collecting Route 66 artifacts during the 1960s and ’70s, when he drove the road several times a year on the way from his Pacific Northwest home to his mother’s house in Mississippi. “People just wanted to get rid of stuff in those days,” he said. “I’d ask someone how much for this road shield or that sign or the old gas pump. He’d say, ‘If you’ll haul it away in your truck, you can have it for nothing.’” Before long, Pritchard housed a trove of Route 66 treasures in two warehouses.

In 1998, Pritchard learned that the general store was for sale. He sold his commercial glass company in Washington State and bought the property. The Pritchards spent a year putting the place back together and opened in March 1999. “It took off so quick, I was overwhelmed,” he said. “The second year I had to hire people. All the car guys, the car clubs, the Harley-Davidson riders, the tour buses stop here.” Today, he adds, “I’d say 90 percent of the people coming down this road are foreigners. One French guy told me, ‘We say in France, if you want to see the face of America, drive 66.’”

The patched, two-lane road crossed through Kingman, paralleling the wide, smooth pavement of I-40, then split off and headed into high desert, switchbacking over the angular Black Mountains, not a person or another car in sight. Static drifted in and out over my radio. I pushed the off button, content to move on in the silence of the empty road.

“Route 66 isn’t just about nostalgia. It’s become an American icon,” Roger White told me. He’s a transportation curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where a 40-foot-long stretch of the road is on permanent exhibit. “It is woven through the social tapestry of the United States from the 1920s through the ’50s. It opened an all-weather route from Chicago to the West and was the route for the migration of Dust Bowl families, military mobilization during World War II, for veterans seeking new homes and vacationers looking for fun.” The road, he said, “was a catalyst for the belief, if there is a better life out there, the highway will take me to it.”

I stopped at the 109-year-old Oatman Hotel for a buffalo burger, then drove on to Topock. I parked in the shadow of the bridge that carries Route 66 over the wide, calm Colorado River. On the far bank was California, the beginning and the end for so many American believers.

David Lamb is a frequent contributor to the magazine, and Catherine Karnow photographed Smithsonian stories about Big Sur, Amerasians and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.